“To See What Freedom Meant:” April 9, 1865 (Sesquicentennial Spotlight)

/Soldiers at Appomattox Court House, Virginia in April of 1865

Of the finals days of civil war former Virginia slave Samuel Spottford Clement remarked, “General Lee surrendered to General Grant and the Southern Confederacy was at an end…On the 8th day of April late in the evening the field hands could hear the boom of cannon and the crack of musketry from the battle field near Appomattox Court House. The old field hands prayed in concert that the Yankees might win the fight. God heard their prayers that they had prayed, not only then but the prayers had been sent up three hundred years by the negro suffering slaves.”

Much has been made of the surrender at Appomattox Court House, Virginia on April 9, 1865. Historians note that myth surrounds those final bedraggled days of the Army of Northern Virginia, the magnanimity with which Union soldiers welcomed their fellow Americans back into a nation at peace, and the causes won and lost in the subsequent years. Though it took months for the rest of the remaining Confederate forces to surrender their arms, no moment stands more clearly in historical memory as marking the end of the United States’ most costly war than the meeting in which Robert E. Lee surrendered his forces to Ulysses Grant. While myth may obscure some of the more concrete realities of that day – what was with Wilmer McLean anyway? – the peace wrought by those two great generals was nothing short of remarkable both for what it ended and what it began.

As the armies neared Appomattox Court House in April of 1865, they did so as shadows of their former selves. Gone were the grand armies of 1863 and 1864, and in their place stood wearied, veteran soldiers who had witnessed a new, unrelenting style of war in the trenches of Spotsylvania Court House and Petersburg. The Army of Northern Virginia dwindled into almost nothing, plagued by desertion and starvation. By the time the men reached Appomattox Robert E. Lee could count only 8,000 infantrymen under his command armed and fit for service. The Union armies that converged on Appomattox likewise looked different. Their ranks were now supplemented by United States Colored Troops, whose presence redefined what the Union armies stood for.

With the fall of Petersburg and Richmond, many already understood what would inevitably come. Though Lee made one last ditch effort to sneak around Grant’s armies and reach Joe Johnston in North Carolina, one wonders if a military man of his skill did not already know that attempt would fail. Lincoln and Grant also recognized that the Army of Northern Virginia no longer stood a chance, and with this reality came the determination that peace would come on Lincoln’s terms; peace would be unconditional surrender both of perceived nationhood and of slavery. Having pushed the 13th Amendment through Congress, Lincoln ensured, as preeminent Civil War scholar Bruce Catton put it, “that the future would be totally unlike the past.”

Appomattox Court House, Virginia as it looks today

On April 9 Lee found himself surrounded and helpless. With no chance of escape he consented to a meeting with Grant to finalize the terms of surrender. Grant guaranteed that former Confederates would not be punished, and Lee, for his part, ensured that his men would not again take up arms against their government. With the unassuming dignity that had marked both their careers as commanders, the two men forged an understanding that reunification would come with as little animosity and as much grace as one could ask of two forces that had spent four years tenaciously seeking one another’s destruction.

As news of the surrender swept the nation, headlines rejoiced that this great conflagration was finally coming to an end. A few select Southern newspapers urged their faithful followers not to give up hope yet, and suggested the same kind of guerilla fighting Lee forbade his men from considering. On April 15, 1865 the Augusta Chronicle cried, “Tell our people that our soldiers are firm, and will continue so if they will but give us moral and material support. Tell them to recognize the danger and prepare to meet it. We must go forward. There is no retreat!” However, more realistic heads prevailed elsewhere. Of the surrender the New Orleans Times stated, “The end of the war is at hand. For a long time Gen. Lee has been the Confederacy. His surrender makes peace a certainty.” Likewise, Joseph Waddel, a Virginian, explained to his family the state of the soldiers and of the cause, “Arthur Spitzer has got back – he marched three days and two nights, on the retreat from Petersburg, with nothing to eat but a can of corn. – Says he saw men on the road side dying from hunger…Nothing remains for us but submission…” Though in subsequent years as Lost Cause memory took hold Americans North and South would argue that “overwhelming force” was not defeat, on April 9th Confederates under Lee were acutely aware that their fight could pursue no other course but surrender.

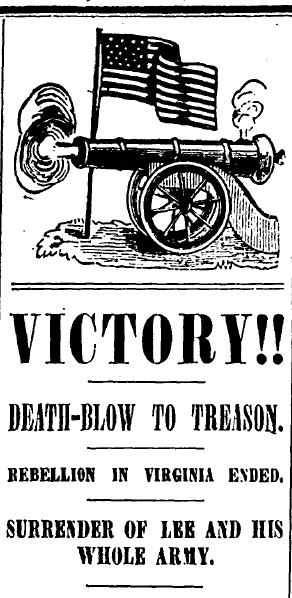

Headline in the Philadelphia Press, April 10, 1865

Union newspapers, for their part, celebrated the victory not only as an end to bloodshed but as proof that their cause had been just and their soldiers true. Headlines did not mince words, declaring, “Union forever,” and celebrating Grant as the savior of the nation. Not hesitating to call the Southern surrender what it was they shouted, “Death-blow to treason!” and “The last prop of the rebellion broken!” One New York soldier described the scene at Appomattox, “Men shouted until they could shout no longer; the air above us was for half an hour filled with caps, coats, blankets, and knapsacks, and when at length the excitement subsided, the men threw themselves on the ground completely exhausted.” Though he intended only to describe his fellow soldiers, this observant New Yorker’s words also describe his triumphant but fatigued country.

In the ensuing days the reunified United States would erupt in wild jubilation and heart-rending despair, and in the complexity of the aftermath of Appomattox it is easy to overlook how truly remarkable a moment it was. With simple words and careful consideration, Grant and Lee ensured that the country’s Civil War would not devolve as so many do into years of guerilla fighting and unending bloodshed. Conflict would of course continue in new, sometimes violent forms, but never again would a political force take up arms in an organized defense of slavery.

Peter Randolph, a slave from Prince George County, Virginia, accurately described the moment when he reflected, “When Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox, and the war was declared at an end, and the slaves free, many of the freedmen in Virginia--those who knew they were free--gathered […] to see what freedom meant.”

Following Appomattox this question was left not just to the freedmen but to the nation, as they attempted to define the freedom for which they had expended so many American lives.

Becca Capobianco is an educational contractor with Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park and an adjunct faculty member at Germanna Community College. ©

Sources and Suggested Reading:

Calkins, Christopher. Battles of Appomattox Station and Appomattox Court House April 8-9, 1865. HE Howard, 1987.

Catton, Bruce. Never Call Retreat. Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, Inc. 1965.

Clement, Samuel Spottford. “Memoir.” Documenting the American South Database, University of North Carolina.

“Glorious News!” The Hartford Daily Courant, April 10, 1865. America’s Historical Newspapers Database.

“Great! Grand! Glorious!” The Boston Herald, April 10, 1865. America’s Historical Newspapers Database.

“Letters from Gens Lee and Gordon,” Augusta Chronicle, April 15, 1865. America’s Historical Newspapers Database.

“Peace a Certainty.” New-Orleans Times, April 15, 1865. America’s Historical Newspapers Database.

Randolph, Peter. “Memoir.” Documenting the American South Database, University of North Carolina.

“The End of the Rebellion!” The Charleston Courier, April 14, 1865. America’s Historical Newspapers Database.

“The end! Surrender of Lee’s Army!” The Daily National Republican, April 10, 1865. America’s Historical Newspapers Database.

Waddel, Joseph. “April 14, 1865.” Valley of the Shadow Database, University of Virginia Library.

Weygant, Charles in Pursuit to Appomattox: The Last Battles. Time Life Collection, 1987.

Varon, Elizabeth. Appomattox: Victory, Defeat, and Freedom at the end of the Civil War. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

“Victory!!” The Philadelphia Press. April 10, 1865. America’s Historical Newspapers Database.