Sesquicentennial Spotlight: Destruction at Sailor's Creek

/Dear Mamma: Our army is ruined, I fear. We are all safe as yet.

These word were written by Colonel William B. Taylor in a letter captured by the Union on April 5, 1865. Lee’s retreat from Petersburg was in its third day and the Confederate army was desperate for supplies. Cut off from the Confederate government in Danville, Lee continued west to avoid the advances of the Union army.

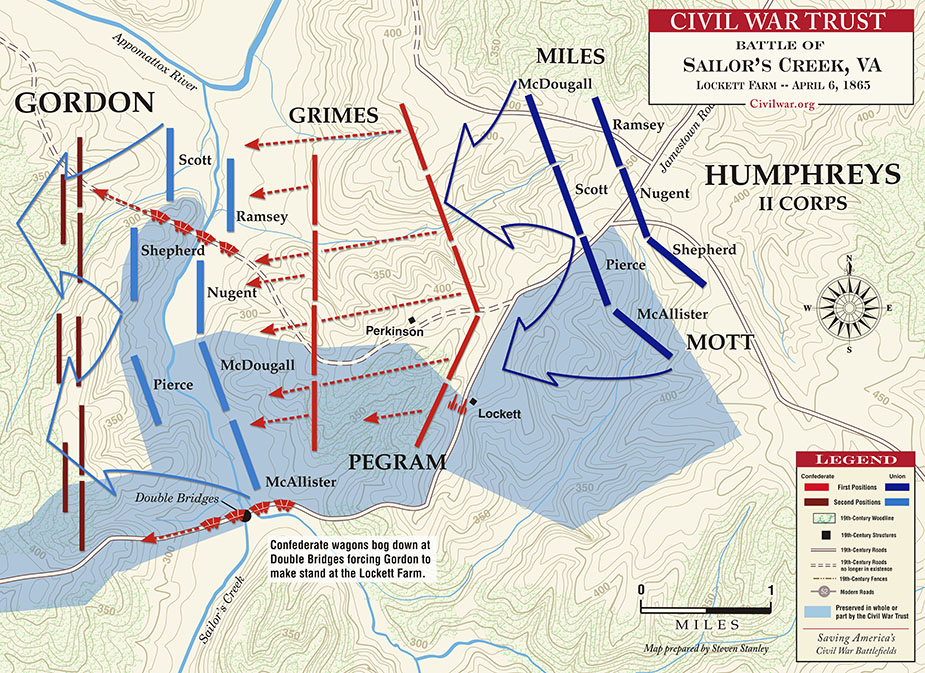

Overnight into April 6, the Confederate army moved away from Amelia Springs, spurred on by captured correspondence revealing that Grant was close behind at Jetersville. General James Longstreet’s men (the combined First and Third Corps) led the way, followed by General Richard Ewell’s Richmond Defense Corps, then the main wagon train, with General John B. Gordon’s Second Corps serving at the rearguard. The march moved slowly, too slowly as they would find out later that day. Major Campbell Brown later wrote: “I saw men apparently fast asleep in ranks, standing up, & walking enough to move on a few yards at a time as the wagons & troops in front gave us a little space. During the whole night our command could not have made three or four miles.”

Around 8:00 am, Andrew Humphreys' Union II Corps caught up with Gordon’s rearguard and started biting into the Confederate column, slowly putting pressure on Lee’s troops. Starting around Deatonville, Gordon’s men formed and reformed against the Union force, trying to delay their progress forward. Gordon recalled the scene after the war:

Fighting all day, marching all night, with exhaustion and hunger claiming their victims at every mile of the march with charges of infantry in the rear and of cavalry on the flanks, it seems the war god had turned loose all his furies to revel in havoc. On and on, hour after hour, from hilltop to hilltop, the lines were alternately forming, fighting and retreating, making one almost continuous shifting battle. Here, in one direction, a battery of artillery became involved; there, in another, a blocked ammunition train required rescue. And thus came short but sharp little battles which made up sideshows of the main performance.

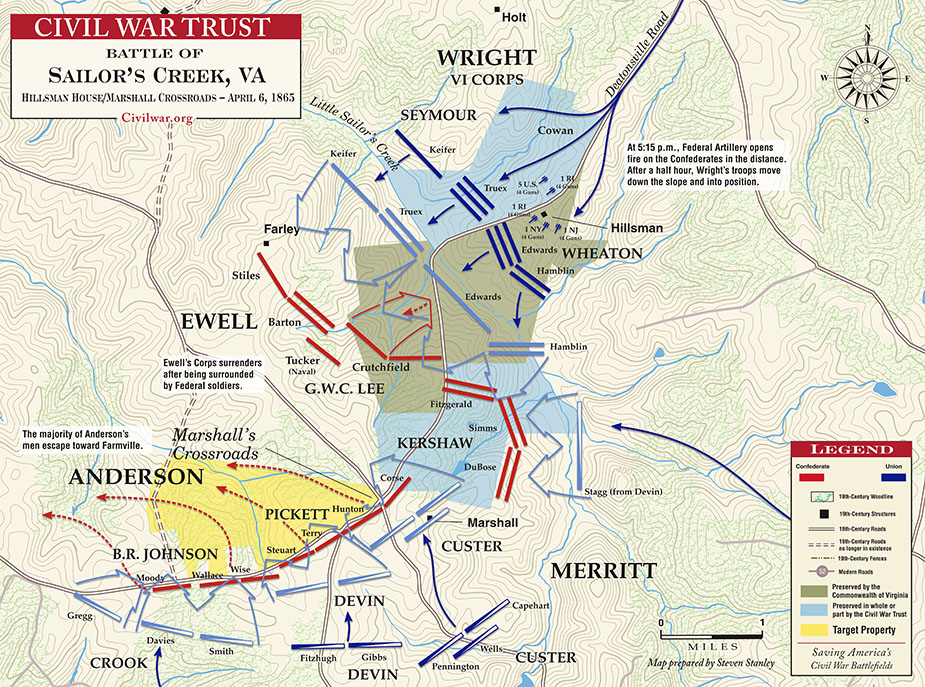

Meanwhile the head of Lee’s column was crossing Little Sailor’s Creek near Holt’s Corner, pursued by Federal cavalry commanded by General Philip Sheridan. At this point a crucial misstep occurred for the Confederates. Forced into engagements by the pursuing Union forces, the troops under Anderson and Ewell stopped at Holt’s Corner to repel their Union attackers and cavalry under General George Custer placed themselves between Gordon’s column and the rest of the Confederate Army. With the way blocked, the Confederate rearguard and wagon train were forced north toward the Double Bridges, where the Little Sailor’s Creek and Big Sailor’s Creek come together, with the hopes of rejoining Lee’s main force.

The Confederate army was now weak and divided into almost three separate battles. To the North Gordon’s men tried to protect the bottlenecked wagon trains as they slowly made their way over the Double Bridges. Humphreys' men kept the pressure on and pushed Gordon’s troops across the river before darkness fell and ended the fighting.

To the South, Ewell and Anderson set up defensive lines between Little Sailor’s Creek and Marshall’s Crossroads, ending up almost back to back in a “U”-like formation facing their individual Union forces. General Horatio Wright’s VI Corps attacked Ewell while cavalry under Generals Wesley Merritt, George Custer, and George Crook attacked Anderson. After a series of assaults, the Confederate forces crumbled and many men surrendered.

The Battle of Sailor’s Creek, many will argue, was a final death knell for Lee’s army. In the day’s engagements Lee lost about a quarter to one-third of his army (depending on which casualty report you look at), 8,800 men out of the roughly 30,000 effectives he had that morning. Of these casualties, around 7,700 were captured or surrendered—one of the largest surrenders without terms during the war. Among this number was almost the entire corps of Richard Ewell—3,400 of his 3,600 men were among the dead and captured. Ewell himself was taken prisoner, along with seven other Confederate generals: Joseph B. Kershaw, Montgomery Corse, Eppa Hunton, Dudley M. DuBose, James P. Smith, Seth Barton, and Robert E. Lee’s son, George Washington Custis Lee. Anderson’s corps lost around 2,600 out of 6,300 and Gordon’s casualties numbered at 2,000.

Viewing the destruction of Anderson’s and Ewell’s men, Lee reportedly exclaimed, “My God! Has the army dissolved?” As Lee pondered his options once the fighting had ceased for the day, he understood the destruction of his army that had happened on April 6 at Sailor’s Creek. Later that night he remarked to General William N. Pendleton, “General, that half of our army is destroyed.”

General Sheridan wrote that night to General Grant reporting the day’s success, remarking, “If the thing is pressed I think that Lee will surrender.” Learning of Sheridan’s message from his location at City Point, President Lincoln sent his own missive to Grant: “Gen. Sheridan says, ‘If the thing is pressed I think Lee will surrender.’ Let the thing be pressed.”

And press they did.

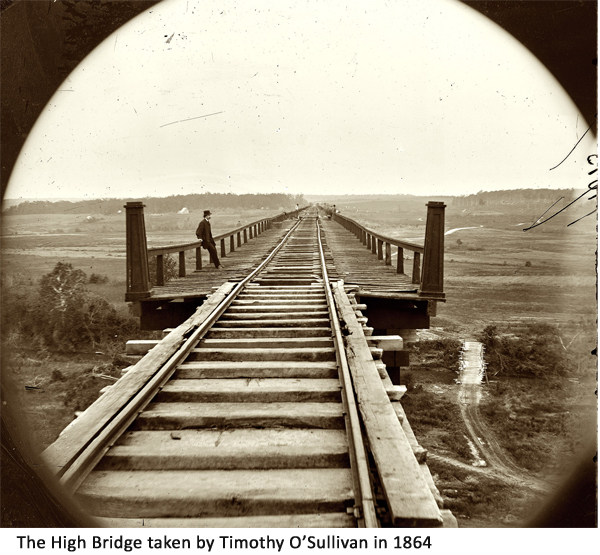

Lee’s only escape would be through High Bridge at Farmville, where his commissary general had rations waiting for the army. From there he could either swing south to join Johnston’s army or race west to escape the pursuing Union army. As the army headed toward Farmville, Lee ordered High Bridge and the nearby wagon bridge over the Appomattox to be burned to stop Federal pursuit.

All day April 7th, Confederates straggled into Farmville, organizing themselves after the fighting of the day before and collecting the first rations since Petersburg. As his men slept and ate, Lee reorganized his army into two corps under Longstreet and Gordon and prepared to march.

Suddenly news arrived that the Federal troops had arrived too quickly at the bridges across the Appomattox and had managed to douse the fires that the Confederates had set hastily to stop their advance. Lee’s men were no longer safe at Farmville. Once again, Lee was on the run as Grant’s troops poked at his army at Farmville and again at Cumberland Church.

That evening General Grant sent the first message to Lee requesting his surrender:

GENERAL: The result of the last week must convince you of the hopelessness of further resistance on the part of the Army of Northern Virginia in this struggle. I feel that it is so, and regard it as my duty to shift from myself the responsibility of any further effusion of blood, by asking of you to surrender of that portion of the C.S. Army known as the Army of Northern Virginia.

Grant received a reply the next morning:

GENERAL: I have received your note of this date. Though not entertaining the opinion you express on the haplessness of further resistance on the part of the Army of Northern Virginia, I reciprocate your desire to avoid useless effusion of blood, and therefore, before considering your proposition, ask the terms you will offer on condition of its surrender.

Talk of surrender had begun, but for the moment the trains of rations plugged westward, and so did Lee, towards the depot at Appomattox Courthouse.

Portions of Sailor's Creek have been preserved and are now open to the public: http://www.dcr.virginia.gov/state-parks/sailors-creek.shtml#general_information

Further Reading:

Chris Calkins. The Appomattox Campaign, March 29-April 9, 1865. Lynchburg, VA: Schroeder Publications, 2008.

William Marvel. Lee's Last Retreat: The Flight to Appomattox. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2002.

Derek Smith. Lee's Last Stand: Sailor's Creek, Virginia, 1865. Shippensburg, PA: White Mane Books, 2002. (all quotes in this article come from this source)

Jay Winik. April 1865: The Month that Saved America. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2001.

Kathleen Logothetis Thompson graduated from Siena College in May 2010 with a B.A. in History and a Certificate in Revolutionary Era Studies. She earned her M.A. in History from West Virginia University in May 2012. Her thesis “A Question of Life or Death: Suicide and Survival in the Union Army” examines wartime suicide among Union soldiers, its causes, and the reasons that army saw a relatively low suicide rate. She is currently pursuing her PhD at West Virginia University with research on mental trauma in the Civil War. In addition, Kathleen has been a seasonal interpreter at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park since 2010 and has worked on various other publications and projects.