Sesquicentennial Spotlight: The Battle of Five Forks

/In a letter to his wife on April 1, 1865, Colonel Theodore Lyman, staff officer of the Army of the Potomac, jested, “You will see the April Fools was on the Rebels.” However, for the Confederacy’s war effort, the Battle of Five Forks was anything but a laughing matter.

In the waning days of March 1865, as the armies in both blue and gray languished in the muddy trenches of Petersburg, Ulysses S. Grant still searched for a final, climatic battle. However, since 1861 the Civil War had transformed into a type of warfare very different than lines of soldiers advancing across open, rolling fields. As both armies settled into miles of intricately built trenches and stalemate ensued, that Clausewitzian final battle of apocalyptic proportions seemed increasingly unlikely. The end of the war would come, but in ways not even the premier military leaders of the time expected.

As winter turned to spring, Robert E. Lee’s Confederate Army of Northern Virginia was suffering from a chronic lack of supplies, rising casualty figures, and heavy desertion. Despite these challenges, the Virginian had created an extremely strong line of defenses around Petersburg that the seemingly unstoppable juggernaut that was the Army of the Potomac had been unable to breach. Grant knew that if a weakness on this line could be found and exploited properly, it could not only mean the fall of Petersburg and subsequently Richmond, but eventually the surrender of Lee’s Army and the end of the war.

This opportunity came on Petersburg’s Western Front 150 years ago, on April 1, 1865, at a place where five roads converged. It became not only a battle of strategic importance, but also a captivating study in leadership and reputation. The Battle of Five Forks was brief, but its significance unquestionable.

The days leading up to this battle were a flurry of activity. Grant was hoping to find a weakness in Lee’s line which he could exploit, and also realized that the ability for Lee to hold said line hinged on the Confederacy’s control of the Southside Railroad. If Union troops could threaten the rail line, Lee would either be forced to bring his troops out of the trenches and fight or abandon his position.

With this strategy in mind, Grant prepared federal cavalry under Phil Sheridan to move toward the Southside Railroad. On March 30th, Grant ordered Sheridan to attempt to turn Lee’s right flank and get behind the Confederate trenches.

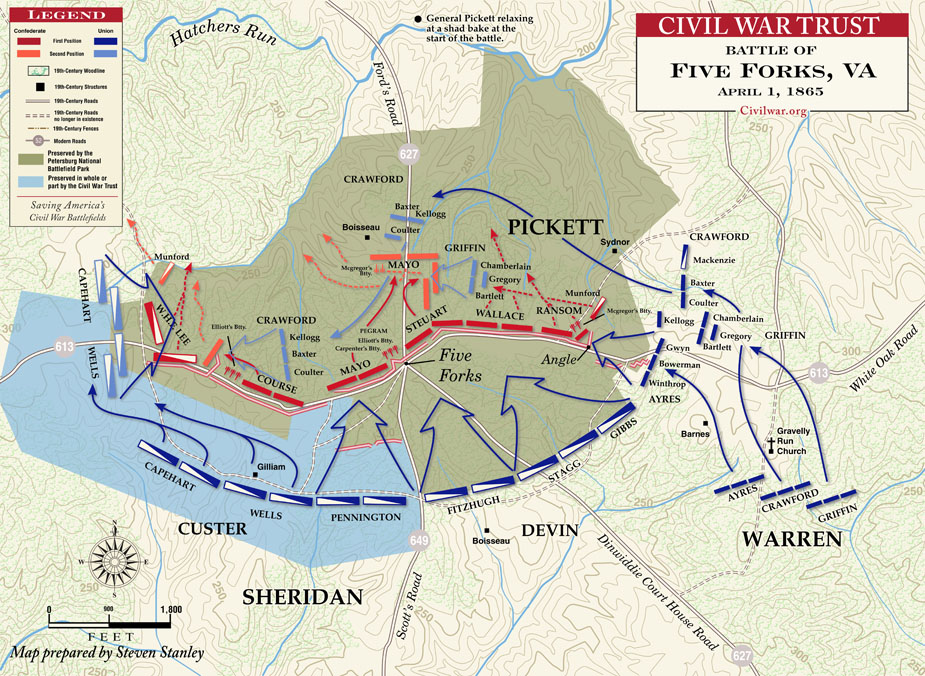

Confederate troops on this side of the line were under the command of General George Pickett, and they were entrenched at a strategic location called Five Forks, where five roads converged at one intersection. After discovering that he would be facing infantry in fortified positions, Sheridan requested that his cavalry troops be supported by the Union Sixth Corps. However, this corps was on the other side of the Union line, and could not be moved in a timely and covert manner. Instead, Grant assigned the Fifth Corps, under General Gouverneur K. Warren, to the task.

Sheridan did not trust the increasingly cautious and unstable Warren, and was not shy about expressing his concerns. As a precaution, Grant sent one of his staff to Sheridan, telling him that, “as much as I liked General Warren, now was not a time when we could let our personal feelings for any one stand in the way of success; and if his removal was necessary to success, not to hesitate.” With this assurance, Sheridan moved forward.

As Warren’s corps moved into position on March 31st, Pickett surprised the Union commanders by advancing out of the trenches at Five Forks and attacking the Union left near Dinwiddie Court House. Sheridan’s cavalry troops were forced to pull back and quickly establish a defensive line to stop Pickett’s progress. At the same time, Warren’s men were attacked by Confederate infantry under General Bushrod Johnson on the White Oak Road, further delayed in joining Sheridan.

Despite the day’s setbacks, Sheridan realized that the Confederate infantry had finally come out of the trenches, and that this could be exploited. Therefore, he established a plan for April 1st. Warren was ordered to move west, trapping Pickett’s now exposed troops, while Warren hit the confederates from the other side. Although Sheridan wanted Warren to be in place by midnight, delays hampered the Fifth Corps movements, and the troops did not even begin moving until 6 a.m. on April 1st, giving Pickett time to react.

Pickett realized what Sheridan did as well; he was incredibly exposed. Furthermore, he also learned that a large body of Union infantry, Warren’s men, was moving toward him. To the displeasure of Lee, Pickett chose to move his men back to the defensive line around Five Forks, giving up the ground he’d gained the previous day. The commanding general did not hide his irritation when giving Pickett the orders, “Regret exceedingly your forced withdrawal, and your inability to hold the advantage you had gained. Hold Five Forks at all hazards.”

By the time Warren was in place for the planned attack, Pickett’s men had long been re-entrenched. A vexed Sheridan came up with a new plan of attack. Dismounted cavalry would feint an attack on Pickett’s right and center, while Warren would attack from the left, hoping to overwhelm the outnumbered Confederates. Warren again moved slowly into place, and his fellow commander was concerned that they would not be able to carry out the attack by nightfall, giving Pickett more time to reinforce his line. Fortunately, the men were in place around 4 p.m.

The Federal attack was not carried out as planned. Pickett’s line, set at an angle, was concealed in a dense section of woods and extended further west than Union intelligence had suggested. Therefore, General Ayres’ division, instead of attacking the front of the line, attacked the angle itself. It could have spelled disaster, as the divisions of Crawford and Griffin, marched past the angle and entirely missed the Confederate line. At this point, Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain showed that the intuition he exhibited at Gettysburg was no fluke. Turning his brigade to attack on Ayres’ right, Chamberlain closed the growing gap between the Union forces, and the rest of Griffin’s division followed. Union forces were now practically on top of the Confederate trenches, and they unintentionally cut off Pickett’s only line of retreat.

Theodore Lyman remarked on this bit of luck by stating, “Thus our movement, which had begun in simple advantage, now grew to brilliant success, and was destined to culminate, within twenty-four hours, in complete victory.”

During the first portion of the battle, George Pickett was famously at a shad bake. The afternoon of April 1st had been a quiet one for Confederate troops, and their commander had not heard of any other movement of the Fifth Corps infantry. Feeling confident that his men could turn away an unlikely attack by Sheridan’s cavalry, Pickett and Fitzhugh Lee accepted Thomas Rosser’s invitation to the now-infamous shad bake, looking forward to a solid meal and a relaxing afternoon. In an even larger error, neither himself nor Fitzhugh Lee informed their subordinates of where they were going or how they could be found. Furthermore, no one was placed in command during their absence.

An auditory trick of the forest kept the sounds of the battle from reaching Pickett and his party, and couriers sent to find the commander were unsuccessful. Therefore, when word of the attack finally reached the shad bake, the battle was well underway.

Had Pickett been present throughout the engagement, it is very unlikely the outcome of the battle would have changed. His men were greatly outnumbered, about 21,000 Union troops to 9,000 Confederates, and both planned and accidental maneuvers gave the Union troops a distinct strategic advantage. However, his leadership at this particular battle was particularly uninspiring when compared to that of Sheridan.

Although Union troops were practically on top of the Confederate earthworks, they were caught in a deadly fire, and the attack began to stall. Realizing that a loss of momentum could spell catastrophe, Sheridan rallied his troops by personally riding along the line, exposing himself to the enemy while shouting reassurances such as “We’ll get the twist on ‘em, boys! There won’t be a grease spot of them left!” Staff officer Horace Porter described him as “the true personification of chivalry, the very incarnation of battle.”

This tactic was risky yet effective. Union troops quickly took the Confederate earthworks, and numerous prisoners with them.

The actual crossroads was held by three Confederate guns under the command of popular artillerist Willie Pegram. When Union cavalry attacked the position, Pegram rushed to give orders without dismounting, and was mortally wounded. The guns were quickly taken, and with them, the crossroads.

By the time Pickett reached his troops, the Confederate force was surrounded on three sides, the line rapidly disintegrating. The general desperately attempted to hold off the Union advance with a single Confederate brigade, hoping to at least give the rest of his force time to retreat and regroup. The vastly outnumbered Confederate troops were quickly overwhelmed, and the Battle of Five Forks was effectively lost.

The battle was over by 7 p.m. The result was about 800 Union casualties to at least 3,000 Confederate casualties, the majority of them taken prisoner. Some sources place the number captured even higher, at up to 5,000. In addition to losing a great number of troops that the Army of Northern Virginia could certainly not replace, this battle meant both a break in Lee’s line as well as the loss of the Southside Railroad. Lee’s line in Petersburg was now untenable.

Despite Union victory, Five Forks was the end of General Warren’s career as a Corps commander. Sheridan removed him of command immediately after the battle, an event Theodore Lyman related with sympathy:

“Poor man! he had been relieved from command of his Corps. I don't know the details, but I have told you of the difficulties he has had with the General, from his tendency to substitute his own judgment for that of his commanding officer. It seems that Grant was much moved against him by this. The General had nothing to do with it. I am sorry, for I like Warren."

This battle also exacerbated tensions in the already poor relationship between Robert E. Lee and George Pickett. Lee’s conviction of Pickett’s general incompetence grew, leading him to remark a few days after the battle, “Is that man still in the army?” This mirrors the general impression many have of Pickett even now as a bumbling, at times comical, figure. Conversely, Pickett once again blamed Lee for the decimation of his men. Referring to Lee derisively as the “Great Tyee,” or big fish, in a letter to his wife, Pickett exalts the bravery of his men in impossible circumstances, as well as referencing his troops’ loyalty to himself:

“All is quiet now, but soon all will be bustle, for we march at daylight. Oh, my darling, were there ever such men as those of my division? This morning after the review I thanked them for their valiant services yesterday on the first of April, never to be forgotten by any of us, when, to my mind, they fought one of the most desperate battles of the whole war. Their answer to me was cheer after cheer, one after another calling out, ‘That's all right, Marse George, we only followed you.’”

The feud between the two men would not end with the war, and due in large part to the elevation of Lee’s standing in American memory, Pickett’s reputation continued to suffer in the 150 years since.

Perhaps the greatest and most long-term impact the Battle of Five Forks had on a leader was on Ulysses S. Grant. After hearing the news of success, he simply remarked, “I have ordered a general assault along the lines.”

With those orders, following a rapid victory at a now-quiet crossroads, the final days of the Civil War commenced.

"The Battle of Five Forks" is the latest post in our Sesquicentennial Spotlight series. As we move through the 150th anniversary of the final year of the American Civil War, Civil Discourse will revisit the major battles and events that shaped the war's conclusion and its legacy. Keep an eye out for further posts in our Sesquicentennial Spotlight series. Previous installments explored the passage of the 13th Amendment and Fort Fisher.

Becky Oakes, a graduate of Gettysburg College, is currently finishing her master’s degree in 19th-century U.S. History and Public History at West Virginia University. Becky’s research focuses on Civil War memory and cultural heritage tourism, specifically the development of built commemorative environments. She also studies National Park Service history, and has worked at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park, Gettysburg National Military Park, and the Civil War Institute at Gettysburg College.

Sources and Further Reading:

Bearss, Edwin C., with Bryce Suderow. The Five Forks Campaign and the Fall of Petersburg, March 29-April 1, 1865. Edwin C. Bearss and Bryce Suderow, 2014.

http://www.civilwar.org/battlefields/five-forks.html

Civil War Trust. “Map of Five Forks, Virginia (1865).” http://www.civilwar.org/battlefields/five-forks/maps/fiveforksmap.html

Dunkerly, Robert M. “To the Bitter End: Final Months of the War.” Hallowed Ground Magazine (Spring 2015).

Lyman, Theodore, 1833-1897, Letter from Theodore Lyman to Elizabeth Russell Lyman, April 1, 1865, in Meade's Headquarters, 1863-1865: Letters of Colonel Theodore Lyman from the Wilderness to Appomattox. Agassiz, George R., ed., Boston, MA: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1922, pp. 370.

Pickett, George Edward, 1825-1875, Letter from George Edward Pickett to LaSalle Corbell Pickett, April 2, 1865, in The Heart of a Soldier:as Revealed in the Intimate Letters of General George Pickett. Pickett, La Salle Corbell, intro., New York, NY: Seth Moyle, Inc., 1913.

Thompson, Robert. “Two Days in April: April 1, 1865 – The Battle of Five Forks.” http://www.civilwar.org/battlefields/five-forks/two-days-in-april-1.html

Trudeau, Noah Andre. The Last Citadel: Petersburg, Virginia, June 1864-April 1865. Boston: Little, Brown & Company, 1991.