Sesquicentennial Spotlight: Richmond Occupied!

/For four long years the Union and Confederate armies played a morbid game of “capture the capital” along the Virginia/Maryland corridor. The close proximity of Washington, D.C. and Richmond, VA made the two cities prime targets for the opposing armies. Starting at the very beginning of the war, with First Manassas/Bull Run, capturing the enemy’s capital was a prime goal. This strategy led to a corridor of destruction between the two capitals. Confederates pushed north in battles such as First and Second Bull Run/Manassas and Antietam. Union troops pushed towards Richmond in ill-fated campaigns on the Peninsula and near Fredericksburg in 1862.

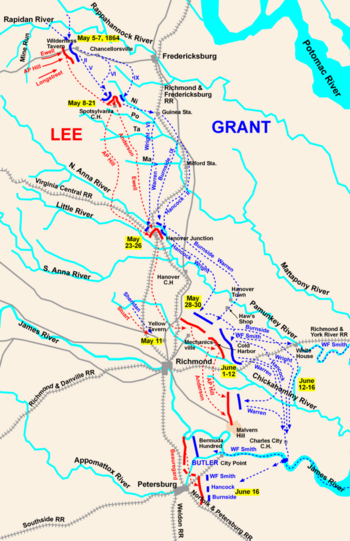

This contest finally came to a turning point with the 1864 Overland Campaign by Ulysses S. Grant and George G. Meade’s Army of the Potomac. Interestingly, Grant’s goal was no longer Richmond, although the campaign would end up there many months after the armies were put in motion in May 1864. Instead, Grant understood the importance of Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Destroy Lee and the Confederacy would stumble. On April 9, 1864, about a month before the start of the campaign at the Wilderness, Grant orders to Meade read: “Lee’s army will be your objective point. Wherever Lee goes there you will go also.” Grant’s goal was to wear down Lee’s army until it broke, fighting a war of attrition against the men in the Army of Northern Virginia.

As a result, the two armies danced around each other down the state of Virginia, clashing repeatedly in increasingly bloody engagements. As the defender of Richmond Lee knew he had to prevent the Union army from reaching the city and Grant knew they could keep Lee engaged if they threatened that city. By the time the armies fought at Cold Harbor in early June, the Union army was just miles outside Richmond, a position they had not taken since the Peninsula Campaign in 1862. But the goal was not Richmond in Grant’s eyes, so instead the armies swung south again and settled into siege lines around Petersburg. There they would stay, for months, until the collapse of Confederate lines in early April and the beginning of Lee’s retreat to Appomattox.

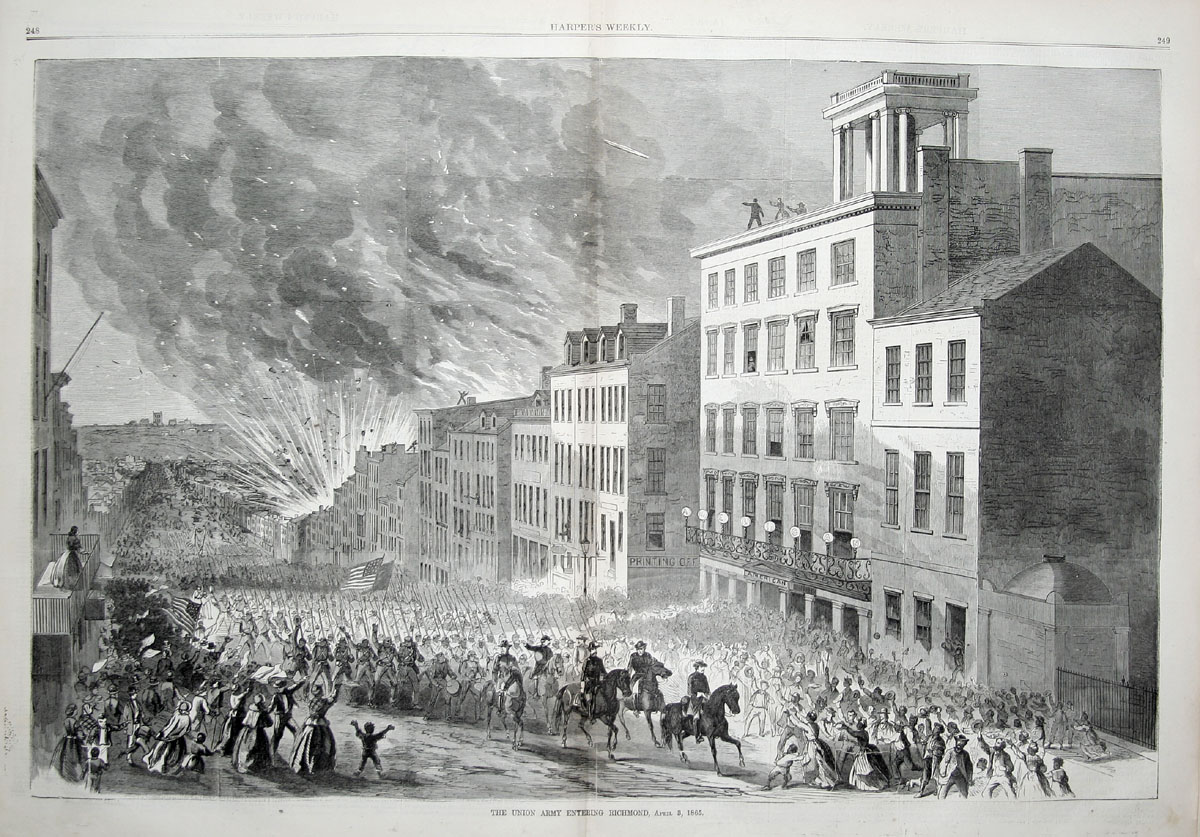

The Union army broke the Confederate lines at Petersburg early on April 2 after the engagement at Five Forks the previous day. Lee knew the position was lost, and the army’s only hope was to move west to find reinforcements and supplies. With the Confederate army moving west, Richmond was now exposed to the Union army. That night the Confederate government and the troops left in the city evacuated in haste, taking the last open rail line to Danville, VA, which would be the last seat of the Confederate government. Throughout the night into April 3, retreating Confederates set fire to portions of the Confederate capital, hoping to destroy supplies before the Union soldiers could reach them.

In the morning of April 3, 1864 the Union troops occupied the former Confederate capital. The first troops to enter Richmond were USCT regiments of the all-black XXV Corps, part of the Army of the James, and the irony and significance was not lost on witnesses from both sides. In a war fought because long-standing tensions over the place of slavery in the United States had divided countrymen into two separate societies, and a war whose meaning had shifted drastically with the introduction of the Emancipation Proclamation two years earlier, the capture of the Confederate capital by men previously held in bondage or considered property by the South was significant to all involved. Imprisoned Union soldiers and African-American slaves met the troops with joy. Prisons and slave pens were opened and the occupants freed, including fifty slaves from the infamous slave jail of Robert Lumpkin. The arriving troops from the Army of the James celebrated the fall of a long-wanted prize, especially since they had not seen as much success in the war as their more famous compatriots in the Army of the Potomac, who now moved to follow Lee’s retreat west. Frederick Chesson of the 29th Connecticut said of his first sight of Richmond: “Right out there in the open in sight of that flaming city, we went wild with excitement of the place and hour—we yelled, we cheered, we sang, we prayed, we wept. We hugged each other and threw up our hats and danced and acted like lunatics for about fifteen minutes, and then we went into Richmond, colors flying.”

On the other side, some Richmond citizens mournfully and fearfully watched Union troops occupy their city; others welcomed the northerners with open arms. Mayor Joseph Mayo offered the surrender of the city with this short note:

The Army of the Confederate States having been withdrawn from the City of Richmond, as Mayor of the City I request that an organized body of troops under a proper officer be sent into the City to protect the women & children and the property until the United States Government may take formal possession of it.

Major Atherton Stevens, serving as an escort from the headquarters of Major General Godfrey Weitzel, commander of the XXV Corps, accepted Mayo’s surrender and issued orders to protect the citizens of Richmond and combat the fires still burning in the city.

Bells ringing through Richmond sounded death notes for the Confederacy. By the end of April 3, Richmond had fallen and Lee’s army was in full retreat west. For the next week the Army of the Potomac would whittle away at Lee’s force as he struggled west to find supplies for his men. Soon the breaking point would come.

Suggested Reading:

Ballard, Michael B. A Long Shadow: Jefferson Davis and the Final Days of the Confederacy. Athens: The University of Georgia Press, 1985.

Nelson Lankford, Richmond Burning: The Last Days of the Confederate Capital. New York: Viking, 2002.

Kathleen Logothetis Thompson graduated from Siena College in May 2010 with a B.A. in History and a Certificate in Revolutionary Era Studies. She earned her M.A. in History from West Virginia University in May 2012. Her thesis “A Question of Life or Death: Suicide and Survival in the Union Army” examines wartime suicide among Union soldiers, its causes, and the reasons that army saw a relatively low suicide rate. She is currently pursuing her PhD at West Virginia University with research on mental trauma in the Civil War. In addition, Kathleen has been a seasonal interpreter at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park since 2010 and has worked on various other publications and projects.