Stone Heroes North and South: The Connection between Mount Rushmore and Stone Mountain

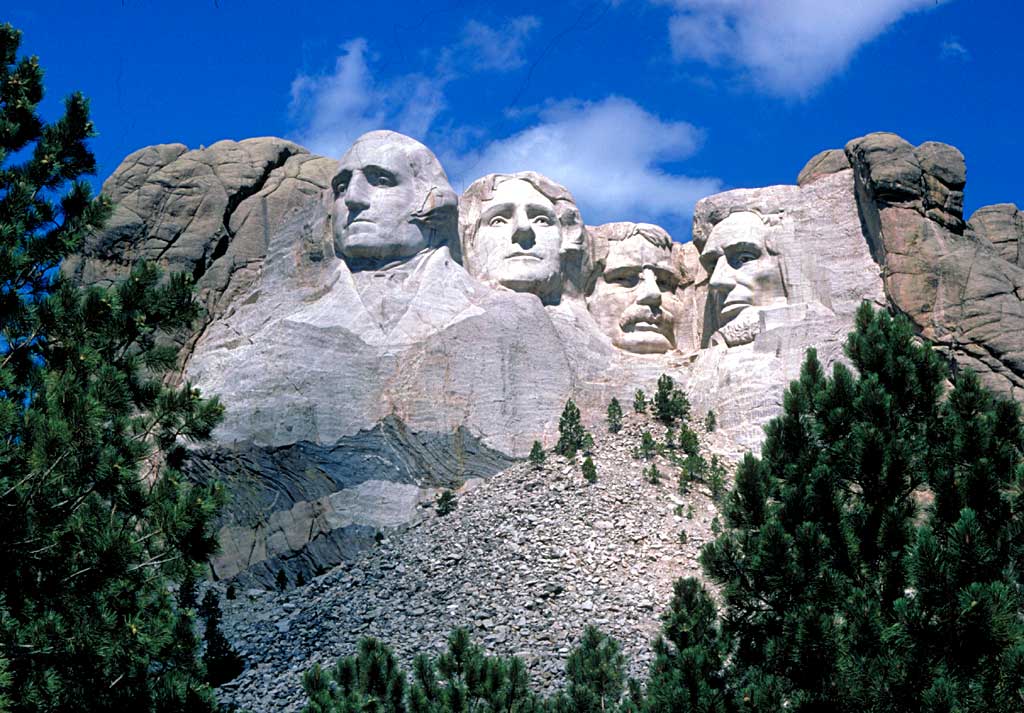

/One displays the heroes of the Confederacy—Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis, and Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson—all on horseback riding across the wide gray canvas that is Stone Mountain near Atlanta, Georgia. The other features four bust-style depictions of famous American presidents—George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Theodore Roosevelt, and Abraham Lincoln—gazing formally from Mount Rushmore over the Black Hills of South Dakota. Each was created out of pride for heritage and nation. Each inspires awe at its size and wonder at the artistic skill necessary to carve such massive.

And each have very different meanings. One is a very nationalistic and patriotic piece featuring four of America’s favorite presidents that was conceived to bring tourism into the area. The other is a monument to the Confederacy led by Southerners who wanted to honor and sustain the Confederate legacy. One honors the United States of America, the other the Confederate States of America. They stand a nation apart, both figuratively and literally (in terms of locations), yet they are connected by the life of one man, the sculptor who set out to complete both projects and ended up finishing neither.

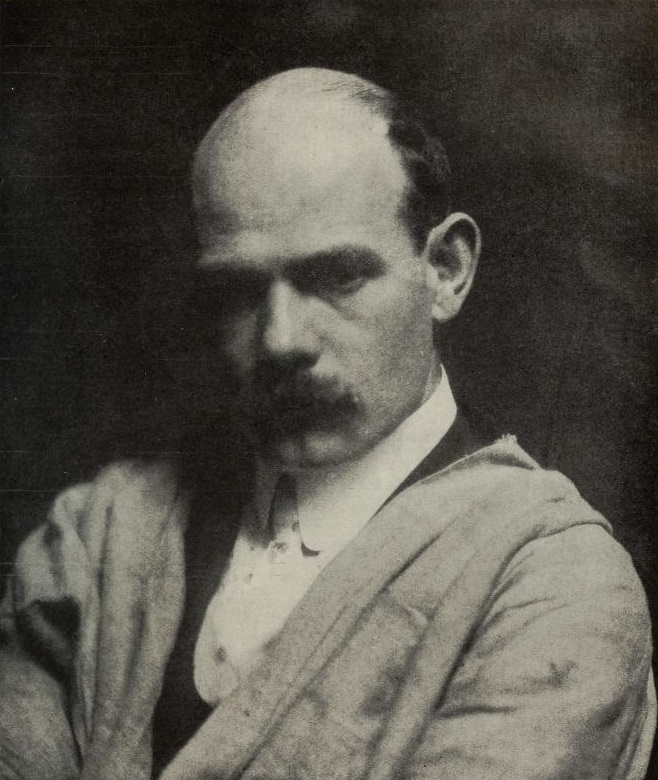

Gutzon Borglum was born just after the end of the Civil War to Danish immigrants who lived in Mormon polygamy (Borglum’s father had two wives who were also sisters). Borglum’s father, Jens Møller Haugaard Børglum, worked as a woodcarver before pursuing a medical practice. As he pursued a medical education, Jens decided to leave Mormonism and left Gutzon’s mother, keeping only his first wife, although he still attended to his children. Gutzon studied at Saint Mary’s College in Kansas and Creighton Preparatory School in Nebraska before going to Paris to train in art at the Académie Julian.

By the time the project of Stone Mountain started, Borglum was already known for monuments to Abraham Lincoln and Philip Sheridan (among others). The Stone Mountain project was conceived in the 1910s, when a southerner was elected to the presidency, the nation’s capital was legally segregated, and the film Birth of a Nation was highly popular. The original idea for Stone Mountain, devised by Atlanta attorney William Terrell and supported by leader of the United Daughters of the Confederacy’s (UDC) Atlanta chapter Caroline Plane, was a bust of Robert E. Lee carved into the side of Stone Mountain. They approached Borglum with their idea, partially because of his renown for his previous work, but also because, despite being a “northerner,” he seemed sympathetic to their cause.

Borglum quickly dismissed the original design proposed by the newly incorporated Stone Mountain Confederate Memorial Association (SMCMA), stating that a bust of Lee would look akin to a postage stamp on a barn door. He presented a much grander vision featuring full figures of Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis, and “Stonewall” Jackson on horseback, riding across the face of the mountain followed by the Confederate army. In addition, Borglum proposed a sanctuary carved into the mountain below the carving, a space for preserving records and contemplation that would honor the women of the Confederacy who were the keepers of the Confederate past as the men had been the protectors of the Confederacy during the war.

Construction at Stone Mountain was slow to begin; initial funding of the project was sluggish and a World War grabbed the attention of the nation. In the 1920s, the project received a breath of new life with a “white male martial ideal” that focused on reconciliation. Stone Mountain was seen as a monument to all the soldiers of the south, including those who had fought FOR the Union in the Spanish-American War and World War I. With this nationalistic narrative, Congress supported the project by authorizing the United States Mint to coin five million silver half dollars designed by Borglum to raise funds.

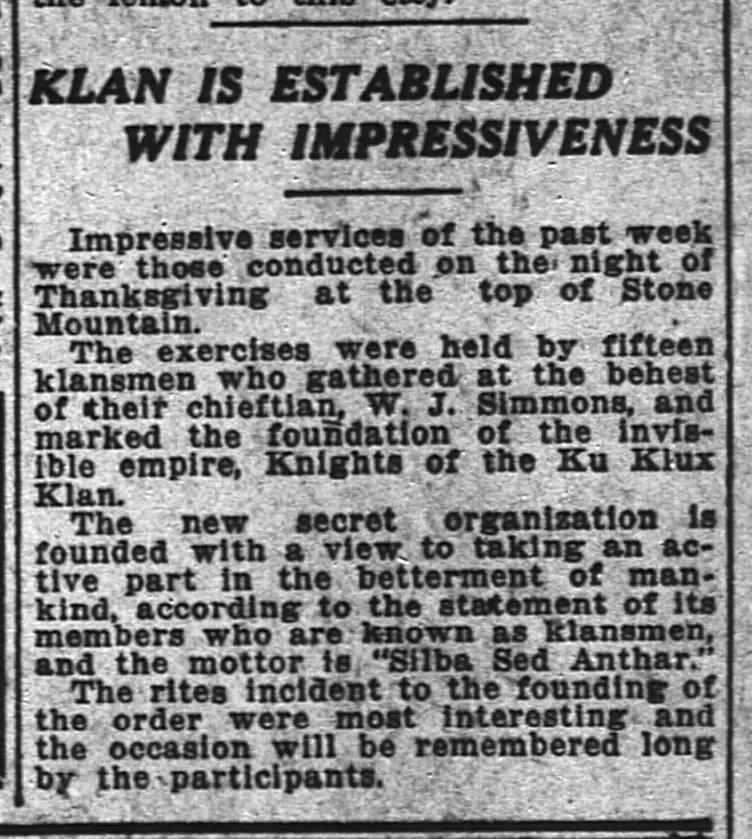

Yet trouble quickly plagued Borglum and the Stone Mountain carving. The completed head of Lee was revealed on January 19, 1924 to the national eye and Congress approved the aforementioned silver dollars a year later, all positive signs for the project’s completion. Yet, infighting between Borglum and the SMCMA over details, and the competing politics of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK), which was closely intertwined with the SMCMA, quickly sent the project into a downward spiral. From the beginning, Stone Mountain had connections with the KKK. The same year Borglum was called to survey Stone Mountain for the project, the KKK reemerged in conjunction with the release of Birth of a Nation and the lynching of Leo Frank. On November 25, 1915 a small group of Klansmen created a new iteration of the Klan, reviving the organization once popular during Reconstruction, with a cross burning on top of Stone Mountain. Borglum himself was a member of the Klan, but ended up on the wrong side of political maneuvering within the organization.

In February 1925, the SMCMA fired Borglum in a highly publicized political and legal fight. Dramatically, Borglum used an ax to destroy his clay models for the carving and left. The UDC quickly tried to bury the controversy and hired Augustus Lukeman to complete the project. The SMCMA had Borglum’s original work blasted off the mountain and Lukeman unveiled his own Lee head on April 9, 1928, the 63rd anniversary of Lee’s surrender at Appomattox. Continued squabbles between the SMCMA and UDC and financial trouble ground the project to a halt and the carving sat uncompleted for several decades. It would not be until the debates over the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s that the newly formed Stone Mountain Memorial Association would see enough support to develop Stone Mountain Park. Even then the carving was not dedicated until May 1970.

While the Stone Mountain project floundered, Borglum quickly moved on to something bigger. Even while still working in Georgia, Borglum was entertaining proposals for a different project in the Black Hills of South Dakota. The idea of a mountain carving there started in 1923 with the South Dakota state historian, Doane Robinson, who suggested carvings of heroic figures from the Old West onto the columns within the granite spires of the Needles. Robinson invited Borglum to South Dakota in 1924 to discuss the project, but after he surveyed the area Borglum proposed a different idea—a carving of presidents to represent national identity, not local or regional interests. Instead of the Needles, which were too soft to carve and in a shape Borglum did not like, he chose Mount Rushmore, an ungainly granite peak that turned its face to the south and east (allowing for the best sun exposure on the carving).

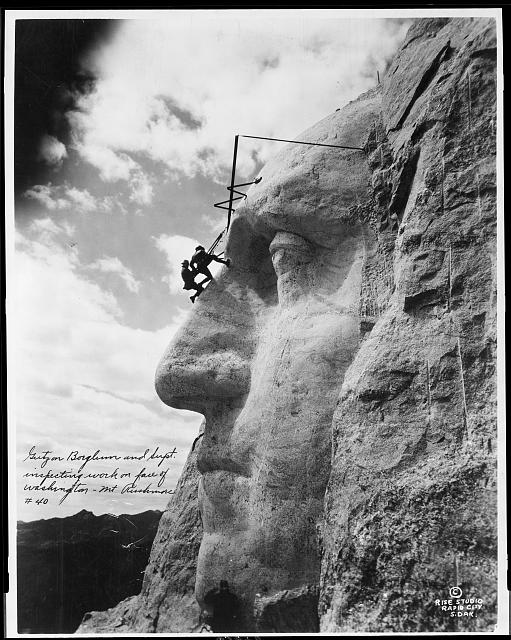

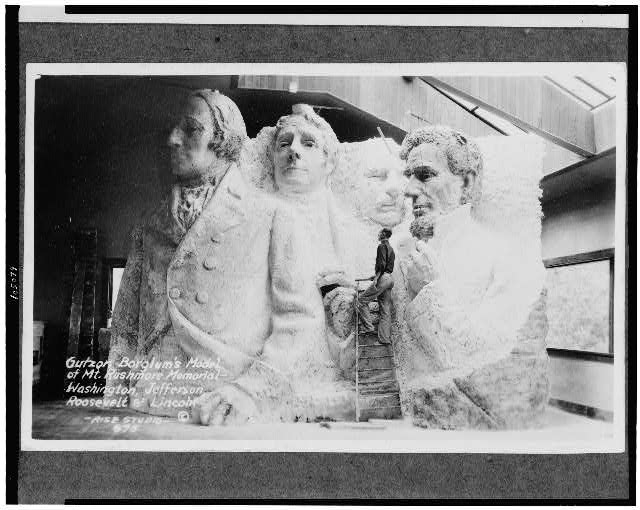

For the carving Borglum chose four presidents that represented the founding and expansion of the United States. Washington and Lincoln were automatically included as the nation’s founder and its savior during the Civil War. The other two presidents, Theodore Roosevelt and Thomas Jefferson, were chosen because of their role in expanding the nation. Like Stone Mountain, Borglum had a grander plan than was eventually completed, including a hall of records, an entablature commemorating America’s important documents and expansions, and a larger carving than what is seen today. But, he experienced some of the same delays and funding problems as in his previous project and carving did not begin until October 1927. Once carving began, however, the project moved forward steadily and without any worker casualties (pretty remarkable considering the length of the project and the type of work being done). For the next fourteen years Borglum, with his young son Lincoln as his assistant, and his team blasted over 400,000 tons of rock off of Mount Rushmore and sculpted the four presidential faces, all while Borglum juggled other projects and traveled to promote and fundraise for the Rushmore project. Washington’s face was dedicated in 1934, Jefferson’s in 1936, Lincoln’s in 1937, and Roosevelt’s in 1939. Federal support in the form of funding and legislation calling for the formation of a Mount Rushmore National Memorial Commission helped move the process along. In addition, Mount Rushmore was placed under the jurisdiction of the National Parks Service in 1933, giving Borglum’s team further assistance in completing the project.

The sculpting of the four faces was nearing completion when tragedy struck in March 1941. After a year of health problems—including two surgeries for prostate ailments that left Lincoln Borglum in charge of the carving—Gutzon was nearly killed by a blood clot while convalescing in the hospital. Two days later, on March 6, another embolism struck and killed the sculptor within minutes.

With Borglum’s death, the government declared Mount Rushmore finished and Lincoln used the remainder of the federal funds to clean up the carving the best he could. Borglum’s vision would never be completed. The full carving was never completed, the entablature was never done, and the Hall of Records was never fully implemented, although a partial vault was placed behind the carving. The original design of the carving included full busts of the president, from the waist up, but only the four heads were completed and some of the details went unfinished when Borglum died.

Today both Stone Mountain and Mount Rushmore draw millions of visitors, as heritage and artistic sites. At both, visitors are viewing the unfinished dreams of the same man. Borglum’s involvement with both sites at time raises a few eyebrows. The same man who carved the nationalistic and patriotic presidential carving at Mount Rushmore, also dreamed up the largest monument to the Confederacy in the nation. The same man who was such a Lincoln fan that he won fame for his bust of the president and named his son Lincoln, was also involved in the Ku Klux Klan. Borglum saw both projects in a national narrative that was more acceptable at the time than it is today. Both projects are monumental reminders that a nation’s past is never simple, never perfectly linear, and often disagreed on as time passes. Borglum’s legacy at Mount Rushmore and Stone Mountain and his acceptance of both into a single national story demonstrates the complex narrative that is the history of the United States.

Kathleen Logothetis Thompson graduated from Siena College in May 2010 with a B.A. in History and a Certificate in Revolutionary Era Studies. She earned her M.A. in History from West Virginia University in May 2012. Her thesis “A Question of Life or Death: Suicide and Survival in the Union Army” examines wartime suicide among Union soldiers, its causes, and the reasons that army saw a relatively low suicide rate. She is currently pursuing her PhD at West Virginia University with research on mental trauma in the Civil War. In addition, Kathleen has been a seasonal interpreter at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park since 2010 and has worked on various other publications and projects.

Sources and Suggested Reading:

Hale, Grace Elizabeth. “Granite Stopped Time: Stone Mountain Memorial and the Representation of White Southern Identity.” In Monuments to the Lost Cause: Women, Art, and the Landscapes of Southern Memory. Edited by Cynthia Mills and Pamela H. Simpson. Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 2003.

Larner, Jesse. Mount Rushmore: An Icon Reconsidered. New York: Thunder’s Mouth Press/Nation Books, 2002.

Taliaferro, John. Great White Fathers: The Story of the Obsessive Quest to Create Mount Rushmore. New York: PublicAffairs, 2002.