“There is Nothing so American as our National Parks:” Administering the Civil War

/On Sunday, April 9, 1933, Horace Albright, the second director of the National Park Service, was given a monumental opportunity. Invited to inspect one of the first Civilian Conservation Corps camps stationed in Shenandoah National Park, he was accompanied by some of the most influential Washington politicians, including the new president, Franklin D. Roosevelt, whose famous first one hundred days in office were well underway. Albright had an agenda aside from reviewing the President’s new relief effort; he wanted to convince Roosevelt of the need to transfer America’s military parks to his own organization.

Sensing the president’s wish for an informal, enjoyable visit, Albright watched as others irritated Roosevelt by loudly and forcefully sharing their opinions. Instead, Albright only commented on what the President was seeing: roads and infrastructure developed by the park service in the last decade. When returning to Washington, the entourage passed over the old battlefield of Second Manassas, and Albright seized his chance. Casually asking if Roosevelt knew that the famous battle had started on the ground they were currently traversing, he opened up the topic of military parks. Explaining the wastefulness and misuse of military parks under other federal organizations, he made his case for their transfer to the National Park Service, which could afford them the same protection as it did the expanses of American wilderness. Concluding his impromptu speech, Albright firmly stated, “The National Park Service ought to have charge of administering all of those parks. It’s right.”

Roosevelt agreed, and because of one car ride, the appearance and interpretation of America’s Civil War battlefields was changed forever.

The administrative shift for federally owned Civil War battlefields of the 1930s was possible because of changing national views regarding environmental and historic preservation. Much of this transformation was due to the fledgling but rapidly expanding National Park Service. Established on August 25, 1916, this federal organization was primarily dedicated to preserving vast expanses of nature in the American West until 1929.

Initial attempts by the War Department and the Department of the Interior to ensure this transfer of battlefield land occurred were favorably received by Congress. Previously administered by the Cemeterial Branch of the War Department, by local entities, or not at all, the executive branch was certain that the Department of the Interior, “specifically created to take care of national parks, was in a position better calculated successfully to do so and was the proper governmental agency to care for the nation’s historic shrines.” Despite this support, the stock market crash and subsequent economic downturn of 1929, ushering in the Great Depression, delayed this transfer. However, a new president of the nation and superintendent of the NPS would ensure this delay would not last long.

With the ascension of director Horace Albright, a long-time history enthusiast, the umbrella of the Park Service expanded to include sites of historic significance. Arguing that “American heritage was made up in equal parts of the unique grandeur of its geography and the heroic deeds of the people,” Albright used the 1932 bicentennial of George Washington’s birth to incorporate the first president’s birthplace, Jamestown, and Yorktown into the National Park system. This action set a standard for other historic parks. In order to be incorporated into the NPS, historic sites had to be considered unique, meaning they were “points or bases from which the broad aspects of pre-historic and American life can best be presented.” Furthermore, included sites were to be symbolic of a “great idea or ideal” that aided in providing a comprehensive depiction of American history. Therefore, sites were not only to be preserved, but also to have an educational component. New historic parks were intended to teach Americans about their own history, through which they could derive lessons applicable to contemporary challenges.

Albright found an ally in Franklin Delano Roosevelt. In an address on the parks given in 1934, Roosevelt made the stirring claim that “there is nothing so American as our national parks.” Explaining the fundamental idea behind the parks, “that the country belongs to the people,” the president asserted that adding and preserving parks not only enriched the nation but the lives of its citizens. Therefore, the inclusion of historic parks and the expansion of the National Park Service was a strong investment by the government in the future. Roosevelt cited the transfer of historic parks, battlefield sites, memorials and national shrines as evidence of the need for both recreational and educational opportunities. Invoking even the idea of American exceptionalism, he stated that “no other country in the world has ever undertaken in such a broad way for protection of its natural and historic treasures and for the enjoyment of them by vast numbers of people.” Not only did the president wish to ensure these historic sites could be accessed by the average citizen, he also wanted to guarantee their relevance. Beyond creating educational opportunities for visiting Americans, the NPS was to aid in fostering a sense of national unity, rooted in a mutual past.

Originally administered by the War Department, Executive Order 6166 reassigned a number of Civil War battlefields to the Park Service on June 10, 1933, a transfer that represented a fundamental shift in the institutional purpose of preserving these battlefields. Under the War Department, battlefields were primarily used either for documenting the veterans’ experience and providing space for their commemoration, or more broadly as training grounds for current military operations. According to Albright, the former administrators of these sites were not interested in catering to tourists, or even necessarily telling the stories of the battlefields. This job largely fell to private guides and local commemorative organizations.

Albright saw historical research and education as far more significant. Under his leadership, the first National Park Service historical research staff was established in 1933, and the number of historians working for the Park Service grew from three in 1932 until World War II, when the organization was the nation’s largest employer of historians.

Changes in American society ensured that this shift was possible. By the 1930s, technological advances such as improved road networks and automobile tourism allowed Civil War battlefields to be experienced on a truly national level. The federal government was also taking an active role in tourism, including enacting legislation to “encourage, promote and develop, by such means as may be necessary, travel within the United States, its territories and possessions.” It was also expanding the number of historic sites preserved. The Historic Sites Act of 1935 was monumental legislation, which was written as “a national policy to preserve for public use historic sites, buildings, and objects of national significance for the inspiration and benefit of the people of the United States.” This far-reaching legislation would allow numerous historic sites to not only be preserved, but also experienced by generations of Americans.

Technology coupled with the development of “national tourism” in the early 20th century. Tourism in this period was a ritual of American citizenship; learning about their nation by experiencing it helped people uncover both their personal and national identities. It also helped people make sense of a national mythology which glorified nature and democracy, when increasing consumerism and industrialism characterized their lives. The emergence of national parks was a huge component of the success of this type of tourism. Describing the “banner year” national parks had in 1934, an article by National Park Service Director Arno Cammerer from 1935 showed the expectation that the parks’ popularity would continue to increase. Claiming that “Americans are on the move to the national parks, for these areas have become a necessity in our economics life to counteract the effects of increased urbanization of our population and to meet the problem of shorter working hours with their resultant leisure,” Cammerer illustrated the attractiveness of these national spaces to early 20th century Americans. More than 15 million tourists visited national parks in 1934, and the expectation was for that figure to increase with every coming year.

Historic parks in particular were vital to forging national identities. One 1936 article eloquently states, “Motor tourists who have a historical bent may find the Epic of America written for them with axe and spade, with trowel and hammer, on a thousand hills and valleys of the continent,” and that the National Park Service is the entity responsible for “the vast program for the preservation and rehabilitation of historic sites and monuments now under way.” Another article gave advice as to how to easily visit major historic sites on the 1095-mile journey from New York City to St. Augustine, Florida. Although an individual could reach Florida after “twenty-seven hours of continuous driving at the average speed of forty miles an hour,” the trip would be more beneficial to the tourist by taking advantages of historical stops along the way. Since every historic site on the eastern seaboard could not be included, the author chose sites under the umbrella of the National Park Service “because of their epoch making character will serve as a nucleus around which to build a motor excursion into antiquity.” By entering historic tourist space, the visitor was seen as entering the past. Battlefields were included in this increase in historic tourism in the 1930s, the “shifting preferences in the choice of recreation spots” towards military parks.

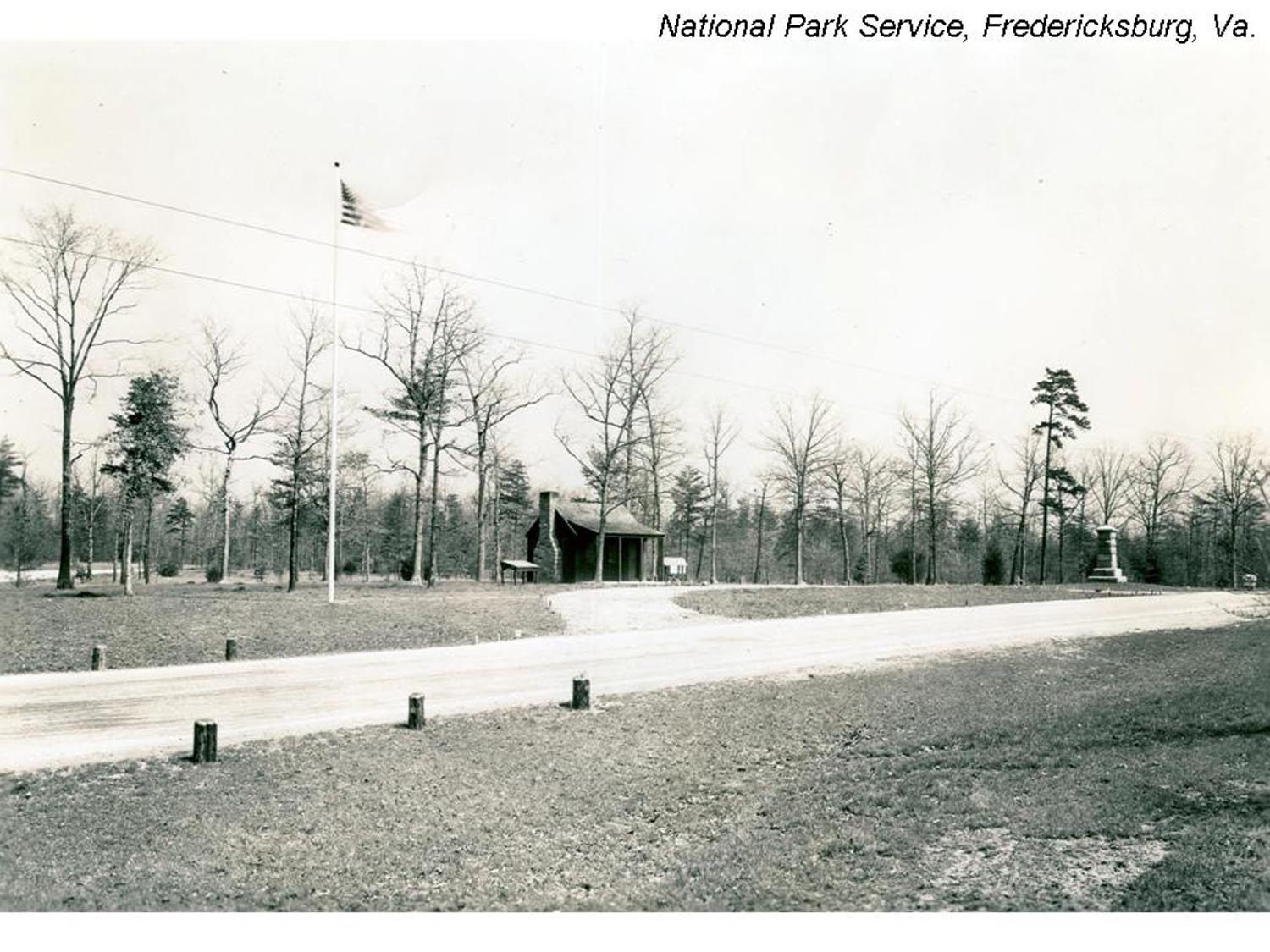

The relationship between national tourism and tourists was a dialogue; visitors to national shrines had a profound effect on shaping the spaces. Not only did the government seek to “popularize the ‘See America First’ movement,” but they also reacted to the needs and desires of the tourists. The relocation of New Deal funds to the betterment of tourist infrastructure was an excellent example of this reciprocal relationship. Physical improvement projects “financed by WPA allotments totaling $2,090,500” were primarily “designed to provide greater convenience and comfort for visitors and include[d] sanitation facilities, water systems and lighting and power plants.” The rising popularity of battlefields, and the need for the education of the average visitor at them, yielded similar results. As of 1936, “the Civil War battlefields, especially those in Virginia, have been restored to a point where the student, or the casual visitor, can obtain a graphic picture of an eventful period in American history.” Tourists at this time were seen as consumers of culture, and their satisfaction was something the government wished to ensure.

As the National Park Service approaches its centennial, over seventy of its current 408 units relate in some way to the American Civil War. The administration, interpretation, and landscape of these lands have changed immensely since Executive Order 6166 made them part of the NPS. However, it is hard to imagine battlefields without this organization.

And it all began on a car ride with FDR.

Becky Oakes, a graduate of Gettysburg College, received her master’s degree in 19th-century U.S. History and Public History from West Virginia University. She is an historian at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park, and is continuing her education by pursuing her PhD, also at WVU. Becky’s research focuses on Civil War memory and cultural heritage tourism, specifically the development of built commemorative environments.

Sources and Further Reading:

“A New Plan for Our Battle Sites,” New York Times, July 22, 1928. ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Accessed January 12, 2015.

Albright, Horace M., as told to Robert Cahn. The Birth of the National Park Service. Salt Lake City, UT: Howe Brothers, 1985.

Cammerer, Arno B. “Parks Look for Big Season,” New York Times, April 14, 1935. ProQuest Historical Newspapers: February 20, 2015.

Everhart, William C. The National Park Service. Westview Library of Federal Departments, Agencies, and Systems, Boulder, Colo: Westview Press, 1983.

“Historic Sites Act of 1935,” August 21, 1935 (49 Stat. 666; 16 U.S.C. 461-467). http://www.cr.nps.gov/local-law/FHPL_histsites.pdf

McKee, Oliver Jr., “Highways Unroll Our History,” New York Times, April 19, 1936. ProQuest Historical Newspapers: February 20, 2015.

Meringolo, Denise D. Museums, Monuments, and National Parks: Toward a New Genealogy of Public History. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2012).

“The President’s Address on Parks.” New York Times, August 6, 1934. PAIS International: Accessed January 12, 2015.

Shaffer, Margaruite S. See America First: Tourism and National Identity, 1880-1940. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 2001.

Speers, L.C., “Bill to Aid Tourist,” New York Times, February 5, 1939. ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Accessed January 12, 2015.

Story, Isabelle F. “Southward over the ‘Battlefield Trail,’” New York Times, November 7, 1937. ProQuest Historical Newspapers, February 20, 2015.