"Wrap the World In Fire," Part III: Confederate Foreign Policy with Great Britain

/Part III in a series; read part I and part II here.

"No you dare not make war on cotton. No power on earth dares to make war upon it. Cotton is king!" -South Carolina Senator James Hammond

To a certain extent, the Confederacy's foreign policy can be summed up by the bold words of James Hammond above. As my previous posts have examined examined possible reasons for British intervention in the Civil War and Union efforts to prevent such an intervention, it is time to turn our eyes South and explore Confederate foreign policy with Great Britain. The Confederacy built much of its policy around "King Cotton," and the result was a foreign policy more disastrous than many could imagine.

At the war's outset, many Southerners surprising possessed a confident, even relaxed attitude toward British recognition and intervention. In the eyes of many Southerners, British aid was a foregone conclusion. Historian Henry Blumenthal helps explain this by outlining two prevailing attitudes amongst the Confederate leadership and populace regarding foreign recognition and intervention.

First, Blumenthal notes the existence of a vague, common perception among many Confederates that Britain and the South had more in common culturally than did Britain and the North, who was in fact a commercial rival. Essentially, this view held that Britain’s interests and cultural ties to the South would lead to recognition and aid. Second, Blumenthal highlights the common belief that Great Britain was so economically dependent upon Southern cotton that she would recognize the Confederacy in order to ensure future shipments of the crop. “King Cotton” would secure Southern independence, as Britain needed to secure “King Cotton”. This belief shaped Confederate foreign policy significantly. Both of these attitudes, however, were united by their belief in both quick foreign recognition and victory.

The Confederate employed two strategies early in the war to try and induce British recognition. First, the Confederacy attempted to use “King Cotton” to force the issue of recognition, leveraging the British economically into aiding the South. Second, the Confederacy held that the Union blockade was ineffectual and thus, according to international law the time, illegal; the blockade could and should be broken by the British Royal Navy. These two strategies shaped Confederate diplomacy with Britain.

In the years prior to the war, the phrase "King Cotton," seemed apt; certainly Southern cotton was king in Great Britain. In 1858, prior to the outbreak of the Civil War, Great Britain exported approximately roughly 78% of its cotton from the American South. Nearly 900,000 English workers worked in either cotton mills or the textile industry; combined with affiliated workers and all their dependents (roughly three dependents per worker) it is estimated that nearly 4,000,000 British were dependent upon the cotton trade and its manufacture for survival. Out of a population of 21 million, this means nearly 1 in 5 Britons depended upon cotton for their livelihood, and 78% of that cotton came from the South. With these figures in hand, it becomes easier to understand the widespread Southern belief that “King Cotton” would force Britain to recognize the South. As the Times of London stated forebodingly, “so nearly are our interests intertwined with America that civil war in the States means destitution in Lancashire [home to Britain's textile industry and cotton mills].” Southerners agreed. As South Carolinian James Hammond boasted, "What would happen if not cotton were furnished for three years...this is certain: old England would topple headlong and carry the whole civilized world with her...No you dare not make war on cotton. No power on earth dares to make war upon it. Cotton is king!"

Southern leaders saw cotton as independence insurance. The Confederacy expected prompt recognition from Great Britain at the start of the war. They expected the specter of a British cotton shortage to force recognition. They expected recognition following Britain’s declaration of neutrality and granting of belligerent status. Yet it didn’t come. Eager to rid Great Britain of her aloofness, Confederate leadership decided to force Britain’s hand to speed up the recognition process. In late 1861, the Confederate Congress announced an embargo on all cotton exports except through Southern ports. Further, an effective yet unofficial embargo of cotton to Europe came into existence. One Southerner boasted to a British reporter, “Why, sir, we have only to shut off your supply of cotton for a few weeks and we can create a revolution in Great Britain. There are four millions of your people depending on us for their bread, not to speak of the many millions of dollars. No sir, we know that England must recognize us.”

The unofficial Confederate embargo of cotton upon Europe and Great Britain in the late summer of 1861 represented a political-power play. Southerners were playing hard-ball diplomacy, and they thought the sooner the British felt the economic pinch for cotton, the sooner the British would offer recognition and break the Union blockade. Indeed, it was the issue of the blockade that created the second great Confederate foreign policy in the early war years.

In April of 1861, the same month President Lincoln announced his blockade, the United States had 40 steamer ships (3 immediately available for duty) and 50 antiquated sailing ships in commission. With this puny, outdated force the United States wanted to blockade over 3,500 miles of Confederate coastline. International law at the time declared that for a blockade to be legal, it had to be real and effective; with a few dozen unavailable and antiquated sea vessels, the Union’s announcement of a blockade was the perfect definition of a non-existent “paper blockade” and thus, illegal. The Confederacy fully expected the British to reject the Union's paper blockade and commence trade with the South. Confederate brought up this issue of the blockade's legality with British officials time and again. In the spring of 1862, Confederate official Edwin De Leon pointed out directly to Prime Minister Lord Palmerston that the paper blockade was “defied with impunity by the blockade runners, who earn millions of money by breaking through its paper meshes.” In Southern eyes, the blockade (at least in its early months) was a sham, and Great Britain should ignore it.

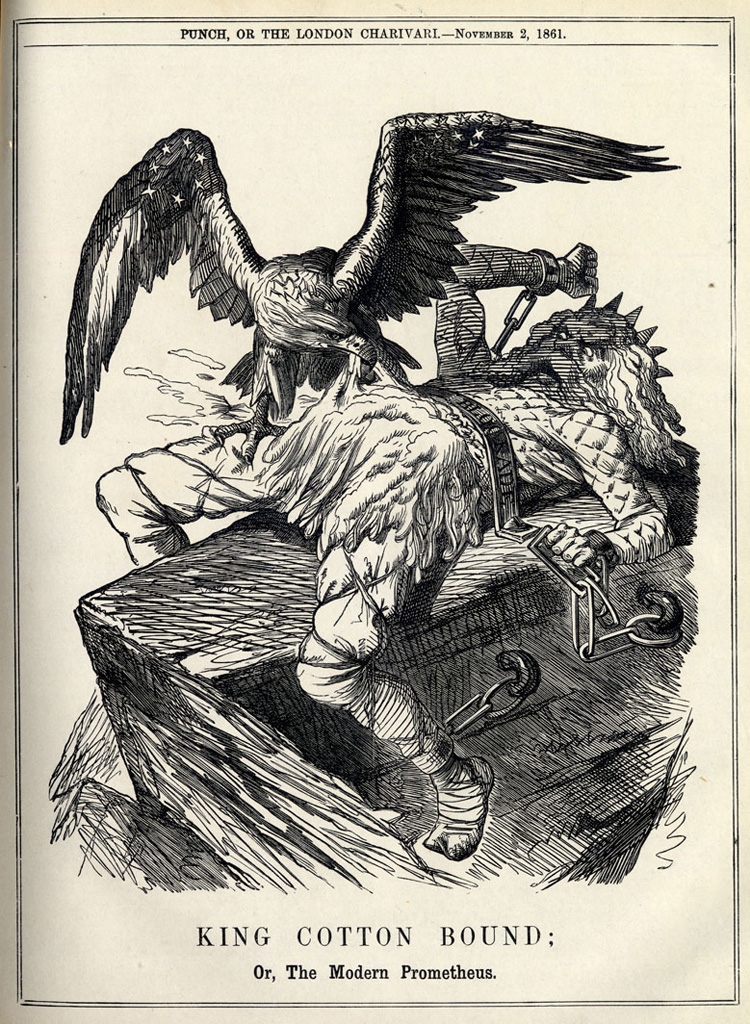

Both of these Confederate strategies, forcing British recognition via cotton shortages and challenging the legality of the Union’s paper blockade, failed. Why? King Cotton diplomacy failed for several reasons. First, Confederate attempts to coerce recognition via a cotton embargo did not sit well with most British. The Economist of London was incredulous, wondering how Southerners could believe that Great Britain would really “interfere in a struggle between the Federal Union and revolted states…simply for the sake of buying their cotton at a cheaper rate.” The Confederate attempts to force recognition were almost offensive. Second, when the cotton embargo came into place in the summer of 1861, there were already significant surpluses of cotton in Britain. These surpluses helped Britain survive the cotton shortages until late into 1862. By the time cotton shortages became serious in Britain, the Union was set to win the Battle of Antietam and issue the Emancipation Proclamation; my last post highlighted how these events ultimately ruined any chance of British intervention. Lastly, Great Britain relied upon Russia, China, and especially India for alternate sources of cotton. By the end of the Civil War in 1865, 85% of English cotton was coming from India (as opposed to 78% coming from the South prior to the war); while Indian cotton could not entirely replace Southern cotton, it provided an alternative source during the war years. King Cotton, diplomatically at least, was not king.

Regarding the blockade, it cannot be doubted that in the war's early months, the Union did not possess the ability to effectively blockade the entire Southern coast. Yet over time, the blockade increasingly strangled Southern ports and the Confederate economy. Perhaps the most damning argument in favor of the blockade was the lack of Southern goods and cotton coming into European ports. If the blockade was so porous, where were Southern goods? The unofficial cotton embargo instigated by Southern leaders lent credibility to the blockade’s effectiveness. Essentially, the Confederate policy of a European cotton embargo undermined its arguments about the blockade's inefficacy. The Confederacy shot itself in the foot with these conflicting policies.

Perhaps the greatest disaster of the Confederacy's foreign policy was not its failure to secure British recognition and aid. Rather, its that the Confederate’s cotton embargo hurt their own cause financially. Thousands of bales of cotton rotted away on Southern docks in an effort to secure British aid. Those bales could have purchased tremendous amounts of rifles, ammunition, machinery, etc. early in the war, both when they were desperately need and the Union blockade was porous. Such commerce would also have boosted Confederate claims that the Union blockade was ineffective. Instead, the South went without and the blockade went unchallenged.

Confederate foreign policy failed to induce recognition or break the blockade. By 1863, it was clear that King Cotton diplomacy had failed, and the Union blockade was a noose ever-tightening. Not only did these policies fail in their objectives, but they actually hurt the Confederate cause by allowing Southern cotton to rot in Southern ports, instead of funding the armies and navy of the Confederate States. Ultimately, Confederate foreign policy stands out as an arrogant, ignominious failure that deprived the South of any chance of foreign recognition or intervention.

Further Reading and Sources

Anderson, Stuart. “1861: Blockade vs. Closing the Confederate Ports.” Military Affairs 41.4 (Dec., 1977): 190-194.

Blumenthal, Henry. “Confederate Diplomacy: Popular Notions and International Realities.” The Journal of Southern History 32.2 (May, 1966): 151-171.

Brauer, Kinley J. “British Mediation and the American Civil War: A Reconsideration.” The Journal of Southern History 38.1 (Feb., 1972): 49-64.

James, Lawrence. The Rise and Fall of the British Empire. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1994.

Jenkins, Philip. A History of the United States. 3rd ed. Ed. Jeremy Black. Willshire, U.K.: Palmgrave Macmillan, 2007.

Jones, Howard. Blue and Gray Diplomacy: A History of Union and Confederate Foreign Relations. Eds. Gary W. Gallagher and T. Michael Parrish. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

Lancashire Cotton Famine. Historic UK.

Lincoln, Abraham. Abraham Lincoln: A Documentary Portrait Through His Speeches and Writings. Ed. Don E. Fehrenbacher. New York: Signet, 1964.

Owsley, Frank Lawrence. King Cotton Diplomacy. 2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1959.

Reid, Brian Holden. “Power, Sovereignty, and the Great Republic: Anglo-American Diplomatic Relations in the Era of the Civil War.” Diplomacy and Statecraft 14.2 (June, 2003): 45-76.

Surdam, David G. "King Cotton: Monarch or Pretender? The State of the Market for Raw Cotton on the Eve of the Civil War." Economic History Review 51.1 (1998): 113-132.

Temple, Henry John (Third Viscount Palmerston). The Letters of the Third Viscount Palmerston to Laurence and Elizabeth Sullivan 1804-1863. Ed. Kenneth Bourne. London: Royal Historical Society. 1979.

All cartoons in these posts came from cartoonist John Tenniel who worked for the British magazine Punch during the Civil War. His fantastic cartoons can be viewed here!