Suicide by Enemy Fire? The Cases of Hill and Garnett

/Death is an occupational hazard for the soldier; it is a basic rule of warfare that there will be casualties. A soldier faces death when they enter battle, and accepts that they must be willing to die for their country, their cause, or whatever motivation has brought them to the front line. But it there a point where being willing to die becomes wanting to die, and does that desire for death border on the question of suicide?

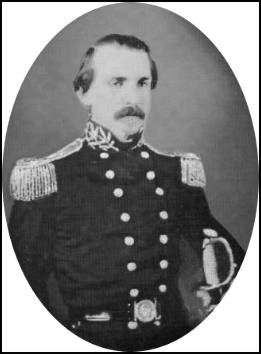

Let us examine two well known Confederate cases, those of Richard Garnett and Ambrose Powell Hill. Now, I understand that painting one or both of these men’s deaths as suicides might ruffle a few feathers, but that is not necessarily my purpose there. I merely want to put the question out there. Did they want to die? Can suicide result from committing to risky behaviors outside the necessity of the situation, not just intentionally harming oneself? Were these two cases “suicide by cop” type situations or were these just casualties of war?

The more murky of the two cases is certainly that of A.P. Hill, and it begins when he was an 18 year old West Point cadet heading back to his third year of school. It was at that point that he contracted Gonorrhea, a severe case that would send him home on convalescent furlough, caused him to repeat his third year of school, and bothered him the rest of his life. In addition to recurrences of venereal disease, Hill faced other health challenges throughout his military service. This would be no different during the Civil War, where his ill health kept him from commanding the front lines several times.

By the time the armies settled around Petersburg, VA in 1864, Hill’s condition was deteriorating severely. His usual health problems were only aggravated by the stress and hardship of campaigning. In March 1865, Robert E. Lee and Hill’s physician urged him to take medical leave so A.P. Hill, accompanied by his wife and children, visited his uncle’s home outside Richmond. During a visit to the capital city, Hill was asked about possible evacuations and replied that he did not wish to survive the fall of Richmond.

Soon after, Hill returned to his lines at Petersburg due to rumors of an all-out assault by Grant’s Union forces. He spent April 1, his first day back at work, riding along his lines. Late in the afternoon he heard the news of the breakthrough at Five Forks, to the west of the main line. The Confederate position was falling apart.

Hill returned to his wife’s side late that evening, but did not rest long because the sounds of Grant’s final assault on Petersburg began early on April 2. Getting up, he asked his chief of staff, Colonel Palmer, to ready the staff and then rode to Lee’s headquarters with couriers to confer with his commander on the situation. During their conference Colonel C.S. Venable of Lee’s staff, broke in to report the situation was worsening along the lines. Hill left the house and mounted his horse so quickly that Lee sent Venable after him to caution him not to expose himself recklessly.

Hill pressed on, now accompanied by Venable and two couriers, Tucker and Jenkins. Once they had proceeded to the lines, the party encountered two Union infantrymen and received their surrender. After sending the two prisoners back to Lee with Jenkins, their attention was drawn to firing along the Boydton Plank Road. Hill ordered Colonel Venable to direct Poague’s unemployed artillery to a position where they could fire on the Union attack.

Now only accompanied by Sergeant Tucker, Hill continued to press to the right. Beginning to worry about this risky behavior, Tucker broke the silence: “Please excuse me, General, but where are we going?” Hill answered, “Sergeant, I must go to the right as quickly as possible. We will go up this side of the branch to the woods which will cover us until reaching the field in rear of General Heth’s quarters. I hope to find the road clear at General Heth’s.” Seeing Hill’s determination, Tucker drew his colt revolver and pulled slightly ahead of the General.

Then Hill suddenly said something that oddly foreshadowed what was about to happen. “Sergeant,” he said to Tucker, “should anything happen to me, you must go back to General Lee and report it.” Coming out into the open they saw a large force of the enemy, but Hill kept the pair moving towards the right. Two Federals ran forward behind a tree and leveled their guns at the oncoming riders. Tucker looked at his superior for direction; “We must take them,” Hill said. Tucker directed him to stay back and rode forward himself shouting, “If you fire, you’ll be swept to hell! Our men are here! Surrender!” This was echoed by A.P. Hill as he also rode forward.

The Pennsylvania infantrymen, Corporal John W. Mauck and Private Daniel Wolford, called the bluff and fired their guns. Woldford’s shot went wide, missing Tucker, but Mauck’s clipped Hill’s left thumb and went through the General’s heart. Tucker grabbed the bridle of Hill’s horse but saw the officer “on the ground, with his limbs extended, motionless.” He made his escape and fulfilled Hill’s orders to report back to General Lee.

While the circumstances of Hill's death leave many questions about his intent, the death of General Richard B. Garnett at the Battle of Gettysburg has been discussed more often as a “death wish.” His situation extended back over a year to the Battle of Kernstown on March 23, 1862. General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson made his battle plans on a report from his chief of cavalry, Turner Ashby, that placed the Union strength far below its reality. When Brigade commander Richard Garnett found his force overwhelmed as a result, he ordered a withdrawal. Seeing the men retreating, Jackson personally tried to stop them. He then relieved Garnett of command, placed him under arrest, and pressed charges against Garnett of cowardice and behaving in an unsoldierly manner. Court-martial proceedings began in August, but were adjourned without a decision. The charges were eventually voided, but Jackson refused to return Garnett to command.

With that, Garnett left his division, but did not give up his place in the war. Lee ordered Jackson to release Garnett from arrest and put him in command of George Pickett’s division while its commander recovered from an injury. When Pickett was promoted to divisional command in Lieutenant General James Longstreet’s corps, Garnett assumed permanent brigade command. He was still in this command when the armies clashed at Gettysburg, PA on July 1-3, 1863. After missing the first two days of battle due to their position in the marching order, Pickett’s Division was ordered forward on July 3, 1863 as part of a mass attack on the center of the Union line.

The nature of the attack convinced many officers to go in on foot, instead of making more prominent targets on horseback. Garnett, however, would have to ride over the open field towards Cemetery Ridge. During the march into Pennsylvania a horse belonging to Captain Robert Anderson Bright kicked Garnett in the ankle, laming him with a painful injury, an injury that Garnett wrote was slow to heal. But he could not refuse to go forward into battle, injured or not. The charges of cowardice had never been settled and, with Jackson’s death in May making a resolution impossible, the only thing Garnett could do was dismiss them through his actions.

Consequently, Garnett rode into the charge on the last day of the Battle of Gettysburg, determined to prove his bravery. He made it all the way across the field, made it almost to the wall before both he and his horse went down. Reports stated that soldiers saw his dead body lying near his badly wounded gelding at the spot they were hit, but Garnett’s body was never recovered and identified. Most likely his remains are buried in an unknown grave among the Gettysburg dead in Hollywood Cemetery; a marker was dedicated to him there in 1991.

Were the deaths of A.P. Hill and Richard Garnett suicide or just more deaths among the hundreds of thousands of Civil War casualties? Were these the desperate acts of men seeking relief from the pain of physical ailment and justification from attacks against reputation, or simply the brave acts of men determined to do their best on the field of war? Due to the personal nature of suicide and decision making, this is one more puzzle in history that we may never figure out.

Suggested Reading

Hess, Earl J. Pickett’s Charge—The Last Attack at Gettysburg. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2001.

Krick, Robert K. “Armistead and Garnett: The Parallel Lives of Two Virginia Soldiers.” In Third Day of Gettysburg & Beyond. Edited by Gary Gallagher. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1994.

Robertson, James I., Jr. General A.P. Hill: The Story of a Confederate Warrior. New York: Vintage Books, 1987.

Kathleen Logothetis Thompson graduated from Siena College in May 2010 with a B.A. in History and a Certificate in Revolutionary Era Studies. She earned her M.A. in History from West Virginia University in May 2012. Her thesis “A Question of Life or Death: Suicide and Survival in the Union Army” examines wartime suicide among Union soldiers, its causes, and the reasons that army saw a relatively low suicide rate. She is currently pursuing her PhD at West Virginia University with research on mental trauma in the Civil War. In addition, Kathleen has been a seasonal interpreter at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park since 2010 and has worked on various other publications and projects.