"I Give Him To Your Charge": Young Soldiers in the Civil War, Part II

/Guest author Rebecca Welker continues her series on the Civil War's youngest soldiers. You can read part I, part III, and part IV here.

"By this time," Charles Bardeen wrote in his memoirs, entitled A Little Fifer's War Diary, "my readers are wondering how my family allowed me to enter the army at so early an age, while I would still go off alone and cry if anybody spoke harshly to me..." My readers are probably wondering the same thing. Modern parents cannot imagine allowing their 13 or 14-year-olds to go to war and yet, as we saw in my first post, many boys fought in both the Union and Confederate armies. Where, we might reasonably wonder, were their parents? What would compel mothers and fathers to allow boys far below the legal enlistment age of 18 to enter the army and put their lives on the line?

The answers to this question are not, of course, cut and dried. In the first place, there were some cultural factors at play which made it more acceptable for boys to take on adult roles, particularly in the military.

The first of these factors to take into consideration is that, unlike modern children, boy soldiers were mostly not full time students, leaving school to enter the army. Those who joined the rank-and-file as privates or musicians came from working-class backgrounds. Before their service, many were holding down adult jobs or if they were very lucky, balancing school with helping to support their families.

Those who lived on farms might attend school around the farming seasons, but when needed at home would be working alongside adults to get crops planted and care for livestock. Boys from cities and towns list their occupations on enlistment forms only very rarely as "student". More often they were working as clerks, smiths, or in similar wage-earning jobs.

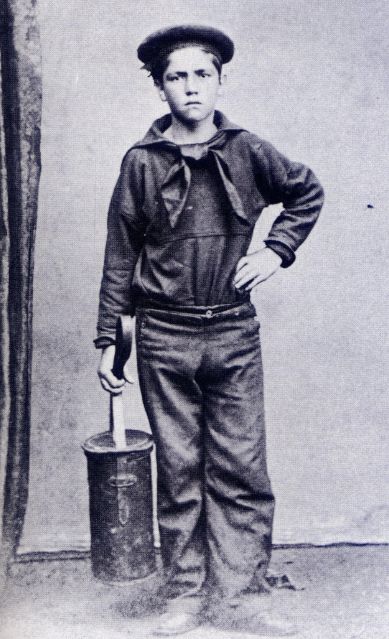

In addition, parents of the 1860s were not unfamiliar with the idea of children serving in the military. The Navy had been enlisting "powder monkeys": boys between the ages of 11 and 18- since it's inception. Serving three year terms, Powder monkeys' primary role was to run powder and shot to guns during battle. Likewise, the Army offered opportunities for boys to enlist as musicians, officially a non-combatant position (more on that in a moment). This is the source of the very romantic popular image of the drummer boy, although many were fifers and buglers as well.

In explaining how they decided to enlist and how they obtained (or evaded the need for) parental consent, former boy soldiers tended to come back to a few common themes. Firstly, a large number of boys hint at, or outright admit to having, difficulties of some kind at home. Whether economic or relational, these home problems made the army an attractive option for them, and a reasonable one in the eyes of their parents.

In the case of 14-year-old Charlie Bardeen, both he and his mother breathed a sigh of relief when he enlisted in the 1st Massachussetts Infantry. Charlie, a staunch abolitionist, becuase he was heading south to fight against slavery; Charlie's mother because she could look forward to enjoying her second marriage without an unruly teenager in the house, all the while knowing that her son was "under authority that could control me".

Although as an adult he was a happily married father and a respected educator, Charlie described himself as having been "...a disturbing element...conceited, boastful, self-willed, disobedient, saucy..." Charlie's mother had considered sending him to reform school after he was expelled from the county grammar school; the army seemed as likely to reform him, and instead he was allowed to enlist as a musician.

Owen Bradford, on the other hand, enlisted in order to get out from under the thumb of a difficult parent. Most of what we know about Owen comes from his brother Peleg's letters; to my knowledge, only one of Owen's letters has survived. It was written shortly after his arrival in camp and is short and to the point. ("Dear Mother, I am well and hope you are the same. I got here after a while. I like first rat. I can't right much tonight. I will right you a letter soon. From your son, Owen. D. Bradford." [sic])

Over the course of Peleg's letters, published in 1997 by his descendants, it becomes clear that all was not well at home. Owen's father, Peleg Bradford, Sr., was an alcoholic and apparently difficult to live with. Owen and his three brothers regularly sent home their army pay for the support of their parents and the five siblings still at home, but they were careful to send the money to their mother. "...[I]f the old man wants a little change you can let him have it but not to fool away," Peleg instructed her.

Peleg had never wanted Owen to enlist, and tried over and over to dissuade him, and to manage from afar a difficult home situation in order to keep Owen out of the army. "There is one more thing I want to tell you, not to let the old man work you to hard," Peleg wrote to Owen, adding to his Mother a few weeks later, "You tell Owen not to let the old man kill him." Remarks of this kind are common in Peleg's letters to his mother and brothers.

The situation at home apparently become untenable, however, and Owen arrived in camp late in December, 1863. There, he soon fell ill with measles and spent more than a month recovering, first in camp and then in the hospital.

At home in Maine, Peleg Bradford, Sr. was moved to take a temperance pledge, and in a letter warmer and more honest than any of the others written to his father, Peleg Jr. admitted, "The reason that we boyes left home was because you was so unsteady... You must not think hard of what I write in this letter... Perhaps you think that I have forgotten you by not writeng to you before, but I have not. I would have sent you money, but... I knew you would not put it to good use."[sic]

Later letters from Peleg to his father discuss the brothers' offers of money to help fund the purchase of a farm for the family. Sadly, the family's newfound happiness was cut short by the death of Peleg Sr. in April 1864, six months before Owen's death near Petersburg, Virginia.

Delavan Miller was in the opposite situation from Owen Bradford. Rather than running away from a difficult home situation, he joined the army in order to keep his family together. In his memoirs which, curiously, are written in the third person, he explains that his father was his only surviving family member and had left Delavan behind when he enlisted in the fall of 1861.

In March, 1862 ("when two months past thirteen years old"), Delavan met a family friend who was home on a recruiting trip and talked him into taking Delavan back to the 4th NYHA with him. "The mother was dead," Delavan explans, "the home was broken up; the little fellow argued that he would be better off with his father."

Nobody wrote ahead to let Sgt. Loten Miller know that his son was coming, but, Delavan said later, "The father was a man of few words... so he brushed two or three tear drops away and went back to the command of his gun squad..."

The need to help support his family financially probably had a lot to do with Rashio Crane's decision to join the army and with his mother Mary's decision to allow him to go. He enlisted in the 7th Wisconsin as a drummer, alongside two older brothers, early in 1864. Rashio was in the army for only about five months before he was captured at the Battle of the Wilderness while serving as a stretcher bearer. On July 23rd, 1864, he died in Andersonville Prison.

After her youngest son's death, Mary Crane filed for a pension, which she was awarded. In her application, she explains to the pension board that she was a widow, with two young daughters still at home, and that she had relied on her sons for financial support.

When she decided to allow him to enlist, Mary Crane may also have hoped that Rashio would be safer because he was with his brothers, or believed that because he was officially a non-combatant he would be out of the line of fire. Certainly, both were attitudes many parents of young soldiers took.

Of course, many soldiers fought alongside friends, relatives, and neighbors. That is the nature of the Civil War's volunteer regiments. But for parents of young soldiers in particular, the thought of the protection fellow soldiers might give their sons helped them make the decision to allow their boys to enlist.

C. Perry Byam, about whom none of his superiors had a kind word to say, was allowed to enlist as a drummer merely because every other male in his family was already in the army. They were considerably older than he and his father was a colonel, and so the army was stuck with him.

Myron Walker's mother personally handed him over to Captain Joseph Parsons of Company C, 10th Massachussetts infantry when he enlisted, with the words, "We give him into your charge." Three years later, 17-year-old Myron was personally handed back by Lieutenant Colonel Parsons, who told his mother, "I remember your charge; he has been a good boy and we have brought him safely back to you."

Not all families were lucky enough to find their trust repaid. Isaac Jarvis and his brother Simon enlisted under their teacher, Captain Oscar Jackson, in the 63rd Ohio; in 1862, Isaac was killed at Corinth, Mississippi, and today is buried in the national cemetary there.

The McMillen family sent six of their sons to the 2nd West Virginia Cavalry. Marion, the youngest, had to wait until he was 16, but in 1863 he joined his brothers in the field. Six months into his service, he was killed by a powder explosion near Hanging Rock, Virginia.

While the mere presence of family or friends in the army was no guarantee that a boy would be safe in battle (and the families, logically, were probably aware of this) it was supposed to be true that musicians were non-combatants and thus, ideally, safer.

Clarence McKenzie had a particularly misplaced sense of confidence that he would be safe as a musician. His mother recalled, "He said to me when he went away, Mother… no one will shoot me. I am only a little drummer boy." Although he was not killed in battle, Clarence was wounded in a gun accident in camp and died shortly after.

Despite their official designation as non-combatants, musicians were rarely left behind when their units went into battle. Whether they provided communication or worked as stretcher bearers, young musicians were on the front lines alongside older soldiers. The fact that they did not carry a weapon themselves did not protect them from the dangers of the battlefield, nor single them out for protection during the fighting.

The 2nd New York lost their drummer during the First Battle of Bull Run, as John B. Wilson of Company C related. "At the third discharge a large shot came amongst our men killing two and wounding one. The ball first passed through the body of one of our drummer boys named [James] Maxwell. He gave but one sigh, and I am sure those who heard it will never forget it."

After the fighting at Sailor's Creek had ended, Delavan Miller and his friends in the drum corps of the 4th New York Heavy Artillery found a Confederate drummer boy, wounded and taken prisoner. "My sympathies were stirred as they had never been before," Delavan recalled when he wrote his memoirs, "as a boy, scarecely 16 years old, was lifted out of the wagon.... He, too, was a drummer boy and had been wounded two or three days before. We got our surgeon and had his wound dressed and gave him stimulants and a little food, but he was... "all marched out," he said... We bathed his face and hands with cool water... [and] before leaving "Little Gray", as we called him, two boys knelt by his side and repeated the Lord's prayer... In the morning the little confederate from the Palmetto state was dead and we buried him on the field with his comrades. Twas war- real genuine war."

Once boys had gotten past the recruiting officers and anxious parents and into the field, the real excitement of service began. They finally saw, as Delavan Miller put it, "War- real genuine war"- sometimes exciting, sometimes tragic, sometimes merely boring. In my third post, I will share the stories of the life these boys came to view as everyday and ordinary.

Rebecca Welker is a graduate of the University of Mary Washington, where her American Studies thesis focused on the depiction of young Civil War soldiers in literature. Today, she works at Historic Ships in Baltimore as a museum educator and as a shipkeeper on the USCGC Taney.

Bibliography and Suggested Reading:

Delavan Miller, Drum Taps in Dixie, 1905.

Charles Bardeen, A Little Fifer's War Diary, 1910.

Melissa MacCrae and Maureen Bradford, ed., No Place for Little Boys: Civil War Letters of a Union Soldier (Civil War letters of Peleg Bradford), 1997.

Dennis Keesee, Too Young to Die: Boy Soldiers of the Union Army, 1861-1865, 2001.