Memories of Hazel Grove: The III Corps at Gettysburg

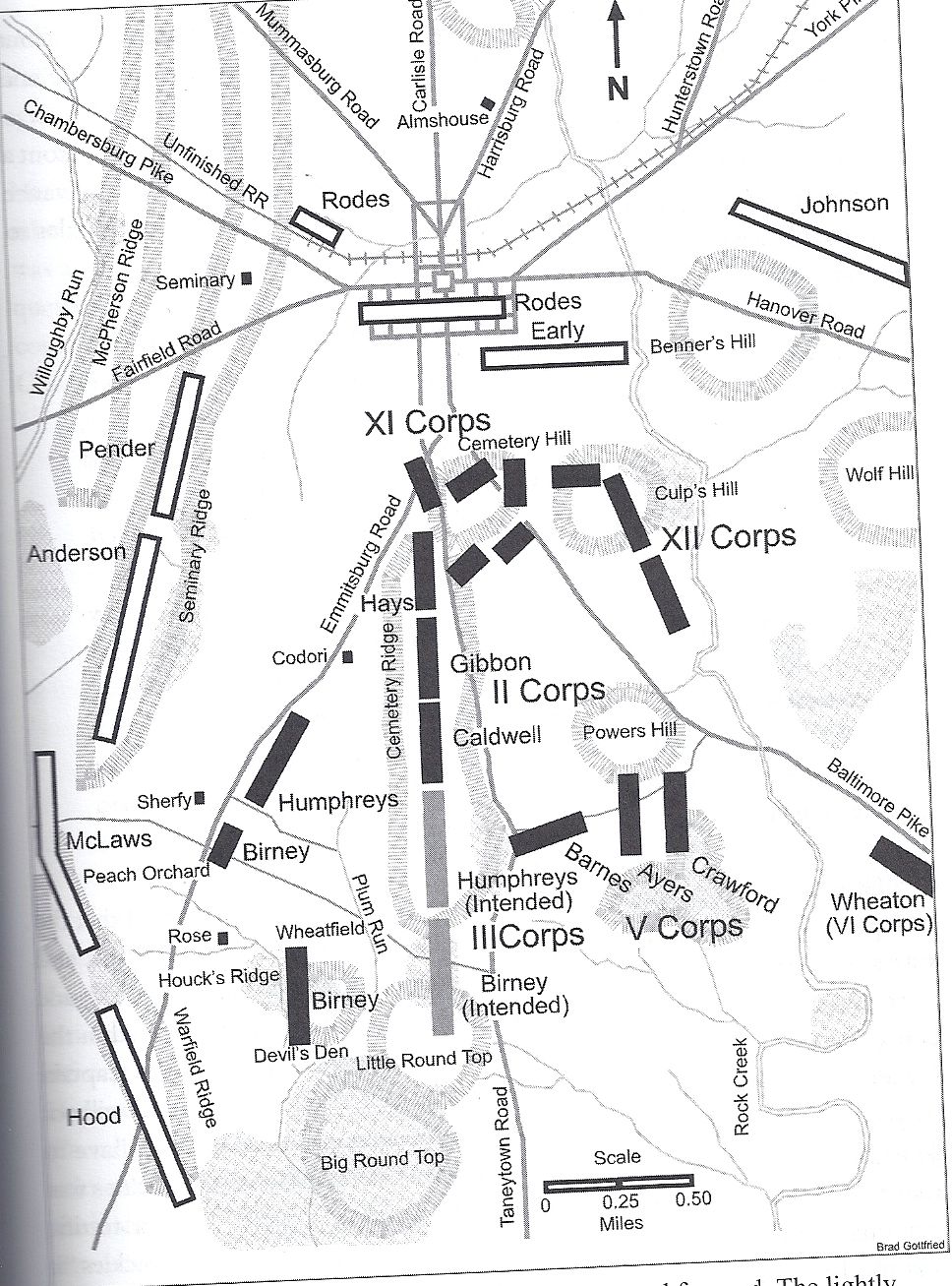

/Daniel Sickles was an infamous figure even before the war began. Sickles is notorious for his role in the Battle of Gettysburg, a role that was debated between generals and officers after the war, a debate that continues today. The III Corps under Sickles arrived at the battlefield over a period of time from the evening of July 1 after the fighting had calmed for the day into the morning of July 2. Meade intended the corps to extend his line along Cemetery Ridge, attaching themselves to the end of the II Corps line and ending at the base of Little Round Top. Whether Sickles misunderstood his orders or willfully disobeyed them, the III Corps ended up in another position entirely.

Sickles was not pleased with his position on the battlefield. His Corps was placed at the end of the ridge, in low ground before the ground rose sharply at the Round Tops. Although Little Round Top acted as a natural anchor and barrier, the terrain was a problem. Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Rafferty of the 71st New York commented on the area in front of them, calling the ground “springy” and “marshy” with many opportunities for the enemy to take cover behind the bushes, rocks, and trees in front of their position. Worse yet, Houck’s Ridge and the Emmitsburg Road were elevated in comparison to their position bringing up concerns about artillery effectiveness and the possibility of the enemy securing high ground in front of them.

Sickles took his concerns to Meade’s headquarters where he claims he received no orders. On the contrary there is evidence that Meade reiterated his orders to extend the II Corps line. Sickles asked if he could move his men according to his judgment, to which Meade replied, “Certainly, within the limits of the general instructions I have given you; any ground within those limits you choose to occupy, I leave to you.” He asked Generals Meade and Warren to accompany him to examine his position, but they were both too busy. Instead General Hunt, the Chief of Artillery, went with Sickles to look at the Union left. Sickles pointed out his issues with the position Meade wanted and the position he proposed to take, and while Hunt agreed that the current position was not ideal for artillery, he refused to formalize that agreement into changing Sickles’ orders, instead saying that he would report to Meade who would then issue new orders if necessary.

New orders did not come, but Sickles continued to be wary of his position against the fear of an enemy attack directly on his position. Despite the choices he made and how they played out, he was correct in predicting where the main Confederate attack would hit. Once there were sure signs that his men would be attacked Sickles decided to change his positions without orders. He pushed his III Corps forward to take high ground, Humphreys' Division extending along the Emmitsburg Road. The Round Tops provided an natural anchor so he refused his other division, that of David Bell Birney, back towards the two hills. This movement probably dictated, more than anything else, how July 2nd and 3rd unfolded.

A benefit of this change in location was that Sickles placed troops exactly where Longstreet’s men were supposed to attack. The presence of the III Corps made the Confederates think on their feet and change their plans on the spot. In addition, the Union did hold high ground in several places, given then an advantage particularly with their artillery.

Primarily, however, Sickles’ decision was disastrous for his III Corps. In pulling Birney’s Division back towards the Round Tops he created a salient in the line around the Peach Orchard that was particularly vulnerable to enemy attack. In addition, his corps found themselves overly stretched out. Sickles’ original position along Cemetery Ridge was around sixteen hundred yards long, covered by the III Corps’ 10,675 effectives on the morning of July 2. This equates to about six or seven men per yard, which Sickles later claimed was not enough men to hold the line. His chosen position, however, was much longer, around 2,700 yards. With the same number of men available, this meant that there were now only three to four men per yard. With this problem of manpower, Sickles did not have enough men to truly anchor his corps at Little Round Top. Instead his line ended on Houck’s Ridge around the rocky outcropping known as Devil’s Den. This meant that there was a small valley between the Union line and their intended anchor.

The Confederate attack hit the overextended III Corps at the front of both divisions. The day was one of charge and counter-charge, best exemplified by the Wheatfield which changed hands six times, but at the end of it the III Corps was overwhelmed and had to fall back to their original position, which turned out to be the stronger one in the end. The Corps lost 4,210 men at Gettysburg, primarily on July 2: 578 killed, 3,026 wounded, and 606 missing. Sickles himself was a casualty, receiving a wound in the leg which led to its amputation and the end of his military career. The Confederates retained the Peach Orchard, Wheatfield, and Devil’s Den, but they had failed to collapse the Union left.

Not only did he devastate his own corps, he placed the entire Union position at risk, particularly because he moved without Meade knowing. By leaving Little Round Top unoccupied a key anchor for the Union line was abandoned, as well as crucial high ground that could dominate the Union position. Fortunately, Brigadier General Gouverneur K. Warren found the undefended position in time to get reinforcements from Colonel Strong Vincent’s Brigade from the Fifth Corps to defend against attacks from Hood’s Division of Confederates. They were able to hold that line, mitigating the overall consequences of Sickles’ move.

In looking at topography, the line Sickles chose was thirty to forty feet higher than his intended position on Cemetery Ridge, so if high ground was only objective it would be considered the superior position. This is what Sickles said about taking that position: “I took up that line because it enabled me to hold commanding ground, which, if the enemy had been allowed to take—as they would have taken it if I had not occupied it in force—would have rendered our position on the left untenable; and, in my judgment, would have turned the fortunes of the day hopelessly against us. I think that any general who would look at the topography of the country there would naturally come to the same conclusion.” In looking at all the factors, however, it was not a wise move.

So why was Sickles so focused on the issue of high ground? Because he had been in that same situation only two months before at the Battle of Chancellorsville.

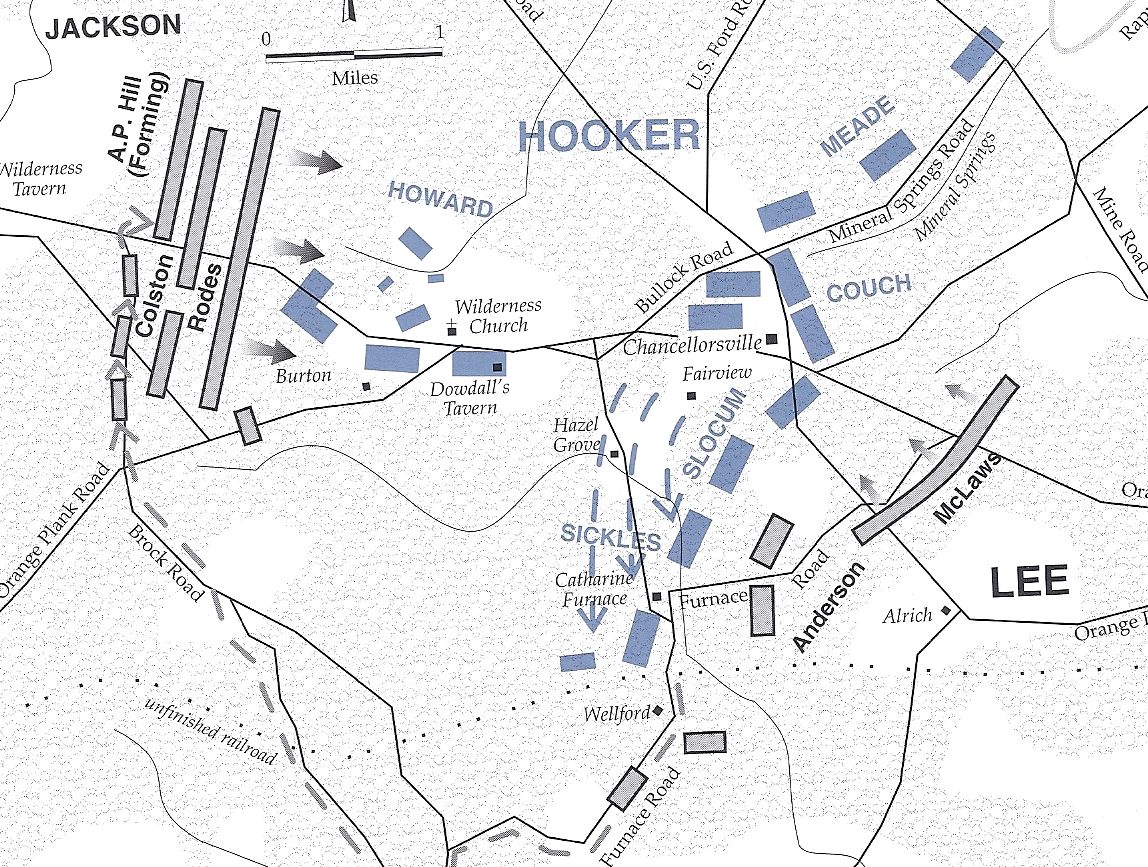

The Chancellorsville campaign, led by General Joseph Hooker, started off as an aggressive movement. The Union army left a diversionary force at their winter camp near Fredericksburg and circled around Lee’s army, crossing the Rappahannock River and approaching the Confederates from behind. It was a daring and preliminarily successful move, but Lee soon figured out Hooker’s plan and came to meet him. From the point of initial contact Hooker’s offensiveness turned to thinking on the defensive. Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson’s massive attack on the Union right on the evening of May 2 made Hooker even more wary. The XI Corps had been sticking out from the bulk of the army when Jackson struck and the corps had crumbled. Hooker looked at his position for May 3 with a very defensive eye and found another problem: the III Corps under Sickles.

Sickles and his men held a position named Hazel Grove, one of the few clearings in the trees that also happened to be high ground. Their position there was a result of the previous day’s fight. When Hooker spotted the Confederate movement that turned out to be Jackson’s Flank March, he sent the III Corps down to engage with them and ascertain their intentions. After a skirmish with Jackson’s rearguard, Hooker perceived that Lee was in retreat (which is a topic deserving of its own talk) and the III Corps fell back towards the main position. They took up position on the advantageous ground of Hazel Grove: clear field, high ground, perfect for artillery and supported by the Union guns at Fairview.

But Hooker found the III Corps position at Hazel Grove to be problematic. It stuck out from the main Union line in a small salient, a formation that was inherently weak. After the XI Corps was routed, Hooker was determined to tighten his defensive line. Sickles could see the advantages of holding the position and tried to urge Hooker to form his lines to include Hazel Grove, but the army commander refused to keep the III Corps dangling like bait for Jackson’s corps. Hooker ordered Sickles to abandon Hazel Grove and pull back into the defensive line around Chancellorsville.

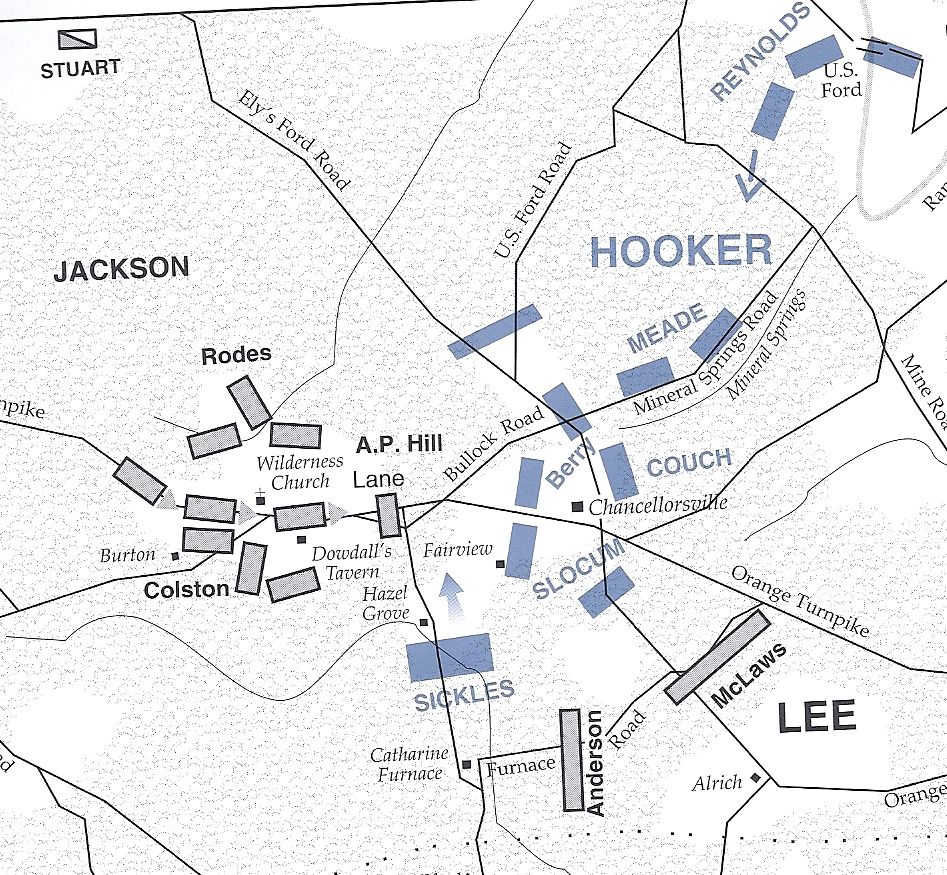

Around 5:30 AM on May 3, Brigadier General James J. Archer’s men advanced on the Union line through the trees and stumbled into Hazel Grove. Instead of meeting the two divisions, plus a separate brigade, and five batteries that Sickles had originally posted there, the Confederates collided with the rearguard of infantry and artillery that desperately tried to hold them off with what little ammunition they had left. Brigadier General Charles K. Graham’s Pennsylvanians were hit with what was described as a “galling fire” and once Captain James Huntington’s artillery faltered, the Confederates swept Hazel Grove clean, taking a hundred prisoners. The way was now clear for Archer to attack the Federal line at Fairview, which he did twice before regrouping at 6:30. He had made it within 70 yards of the main line.

Archer’s attacks came as part of the overall Confederate attack for the third day of the battle. While Hooker was thinking defensively, the mentality of the Confederates was quite the opposite. Their offensive strike the night before was immensely successful and, even though Jackson’s death and the resulting transfer of command through two officers before J.E.B. Stuart took the reigns halted the attack for the night, they wanted to continue the momentum on May 3rd. More importantly, their movements on May 2 put them in a very dangerous position. The Confederate army was divided into two parts, the troops that were part of Jackson’s attack and those who remained with Lee. While the Confederate intentions remained unknown on May 2, their position was weak but not disastrous; now the Union knew that they were both outnumbered and divided, any exploitation of that weakness would be disastrous for the Confederates. On May 3, they needed to fight on the offensive in order to reunite the pieces of their army and strengthen themselves against any Union attack.

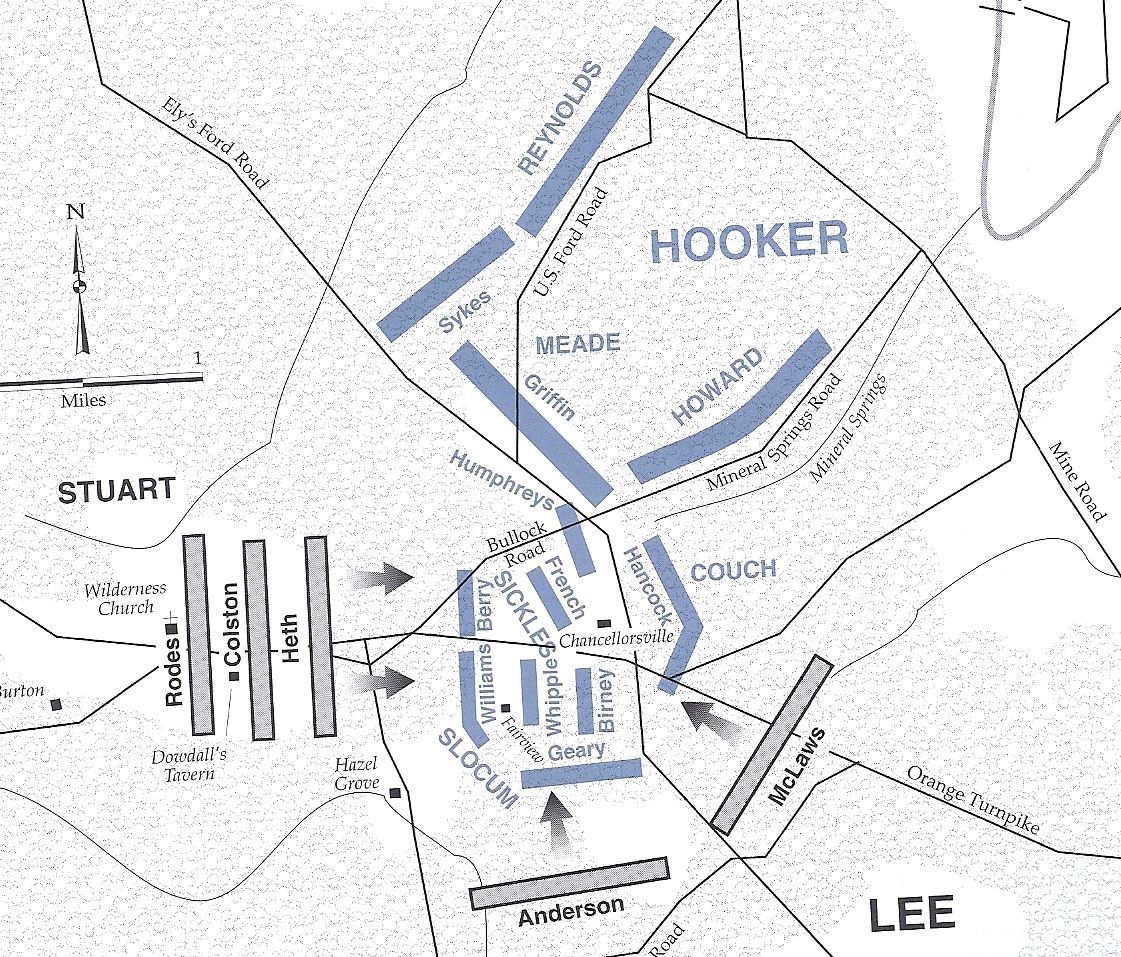

Of course they need not have worried, for Hooker is on the defensive and will remain so for the rest of the battle. Pulling Sickles and the III Corps out of Hazel Grove was just the first domino in the chain reaction. The Union’s position was assaulted on all sides as the Confederates pushed forward to connect their two lines. One by one Union positions were pushed back. With Hazel Grove no longer an obstacle and Confederates in control of the high ground, Fairview was open to attack from both Confederate lines; when that fell, there was no stopping Lee’s army from pushing into the Chancellor clearing itself, the site of Hooker’s headquarters. Before noon Lee triumphantly rode into the clearing around the burning house and inciting a cheer of victory from the troops around him.

The fighting at the main battlefield of Chancellorsville was practically over, although the battles of Second Fredericksburg and Salem Church were just beginning at the same time. Hooker withdrew his army to a defensive position close to the river which he would hold until their retreat on May 5. The morning of May third was bloody, chaotic, and very destructive to both armies. And the outcome seems to hinge on Hooker’s defensive mindset epitomized by his orders to Sickles to pull back from Hazel Grove. A member of the 120th NY fighting in the woods north of the Orange Turnpike lamented that once the Confederates gained Hazel Grove “they became virtually masters of the situation. Nothing was left for the Union forces to do, but to fall back, step by step, which was done in perfect order, every foot of the ground being contested with unabated spirit and constancy, and no position abandoned till it became untenable.”

May third was like a scene from hell for the men fighting it. The pressing Confederate attacks and the faltering Union line, the chaos and confusion of fighting in the Wilderness, the fires that trapped the able and the wounded. May 3, 1863 is still considered the bloodiest morning in American history. 17,500 Union and Confederate soldiers were killed, wounded, or captured in five hours of fighting. This number just exceeds the entire casualty count for the Union army for the entire battle. It equates to one casualty every second for five hours.

Chancellorsville is an experience that remains in the minds of the soldiers and officers who fought it. Memories and consequences linger for days, weeks, years, even decades and centuries. For example, look at “Stonewall” Jackson. His actions at Chancellorsville are still studied by scholars and soldiers alike and his death has spawned all kinds of questions and speculations both during the war and after. Also, take the Union XI Corps. Their rout at Chancellorsville by Jackson’s men ruined their reputation forever; even today they are referred to as the “Flying Dutchmen.” They certainly remembered Chancellorsville going into Gettysburg two months later, but their defeat and retreat there solidified their shame instead of repairing their reputation. Memory is strong, whether you look at psychology or anecdotal evidence. Civil War soldiers and officers remembered their experiences and used them as reference to handle new situations. This is what Daniel Sickles did when he moved his corps to take high ground at Gettysburg, despite the fact that it was against orders and dangerous to the Union line as a whole. The similarity in situations triggered a response in Sickles and he used his previous experience to comprehend and react to his situation. He saw the possibility of another disaster like May third at Chancellorsville if they let the Confederates hold the high ground and moved to prevent that perceived situation.

Suggested Reading:

Ernest B. Furguson. Chancellorsville, 1863: The Souls of the Brave. Vintage, 1993.

James A. Hessler. Sickles at Gettysburg. Savas Beatie, 2009.

Thomas Keneally. American Scoundrel: The Life of the Notorious Civil War General Dan Sickles. Anchor, 2003.

Stephen Sears. Chancellorsville. Mariner Books, 1998.

W. A. Swanberg. Sickles the Incredible. Charles Scribner's Sons, 1956.

Kathleen Logothetis Thompson graduated from Siena College in May 2010 with a B.A. in History and a Certificate in Revolutionary Era Studies. She earned her M.A. in History from West Virginia University in May 2012. Her thesis “A Question of Life or Death: Suicide and Survival in the Union Army” examines wartime suicide among Union soldiers, its causes, and the reasons that army saw a relatively low suicide rate. She is currently pursuing her PhD at West Virginia University with research on mental trauma in the Civil War. In addition, Kathleen has been a seasonal interpreter at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park since 2010 and has worked on various other publications and projects.