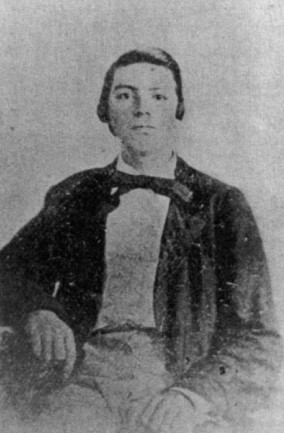

The Unfortunate Case of David O. Dodd: "Arkansas' Boy Martyr" or Fool?

/Young David O. Dodd hung on the end of a rope in the yards of his alma mater, St. Johns’ College. His death was not a merciful one, as the rope stretched and nearly five minutes passed before Dodd finally passed away. Convicted of spying on occupation forces in Little Rock, Arkansas, David had been sentenced to death by Union forces. The date was January 8, 1864, and David Dodd was only seventeen years old.

David Owen Dodd was born in Port Lavaca, Texas in November of 1846. In his youth, his parents had moved the family to Little Rock, in part due to the educational opportunities for David and his two sisters. David attended St. Johns’ College for one year, before a nasty bout of malaria forced him to delay his studies.

The Civil War, as it did to so many American families, turned the lives of the Dodds upside down. In late 1863, Union General Frederick Steele captured Little Rock, Arkansas. The Dodds evacuated south to Confederate-held Camden, Arkansas. But the family still retained connections in Little Rock, and on December 24, David O. Dodd traveled to Little Rock, ostensibly on behalf of his father’s business.

David had seemingly little to fear. Being only seventeen, he was below conscription age at the time and wouldn’t arouse Union suspicions of Confederate service. As proof of his age, he carried his birth certificate with him. Also aiding David’s safe passage was a pass from Confederate General James F. Fagan. Thus, the road to Little Rock through both Union and Confederate lines seemed clear.

Yet the truth behind David Dodd’s sojourn to Little Rock remains murky. Upon receiving his pass from General Fagan, the general remarked, perhaps in jest, that he expected a full report upon David’s return. David’s trip to Little Rock was highlighted by several holiday soirees, and upon his return home, he turned his pass over to Union authorities as he left their lines. Yet Dodd, after leaving Union lines, accidentally stumbled back into them; without a pass this time, he found himself without identification in unfriendly hands. Attempting to provide some identification, Dodd turned over a small, leather book to Union soldiers.

Within the book, the soldiers discovered a series of dots and dashes, quickly determined to be Morse code. The deciphered message pinpointed the precise strength of Union forces in the Little Rock area. David was arrested and taken to the Ten Mile House on Stagecoach Road. The Ten Mile House, still standing today, has a long history of its own. Built in the late 1820’s or ‘30’s, the house stood roughly ten miles south of Little Rock on the old Southwest Trail, which took settlers from St. Louis down to the Red River region in northeast Texas. By the outbreak of the Civil War, the brick home was in use as a Union military post on the outskirts of Little Rock, and it was here that Dodd spent his first night as a Union prisoner.

Dodd was soon transferred to the arsenal in downtown Little Rock, where he was tried and convicted of spying. The Union general in charge of Little Rock, Frederick Steele, offered Dodd his freedom in exchange for the names of those who supplied him with the dispositions of Union forces. “I can give my life for my country but I cannot betray a friend,” Dodd allegedly responded. This bravado—perhaps brave, perhaps foolish—sealed young David’s fate. On January 8th, a day so cold and bitter the Arkansas River froze over, David O. Dodd was hung.

For some, David Dodd was and remains a hero; today, he is oft remembered as “The Boy Martyr of the Confederacy” and “Arkansas’ Boy Hero”. Dodd’s death can easily be viewed as a harsh, bitter end for a boy who was playing a deadly game he hardly understood. Yet in the minds of Union authorities, and with some justification, Dodd was a Confederate spy. The coded messages of Union troop positions in his notebook, and perhaps General Fagan’s offhand remark about receiving a full report, all point to the conclusion that Dodd was very intentionally playing that deadly game. It wasn’t just his father’s business that led him to Little Rock. He received the punishment any other spy would receive-death. Seventeen maybe young, but certainly thousands of young men of a similar age to David were fighting and dying for their respective causes—Northern and Southern.

Today, David Dodd rests in Mount Holly Cemetery in downtown Little Rock (a stone’s throw away from General Fagan’s final resting place as well). He is honored every year by the Sons of Confederate Veterans, and he remains enshrined in local folklore. The unfortunate case of David Owen Dodd fascinates local Arkansans, but also leads to tough questions.

Does the impetuosity of David’s youth excuse his actions? Was he acting under Confederate auspices or did he act alone? Should he be revered as a martyr? Feel free to share your thoughts.

Zac Cowsert currently studies 19th-century U.S. history as a doctoral student at West Virginia University, where he also received his master's degree. He earned his bachelor's degree in history and political science at Centenary College of Louisiana, a small liberal-arts college in Shreveport. Zac's research focuses on the involvement and experiences of the Five Tribes of Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) during the American Civil War. He has worked for the National Park Service at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park. ©