Mental Stress in the Union Army

/The conditions and new experiences of the war were unsettling to the volunteer soldier, and they had to deal with them mentally as well as physically. Some men adapted to the war better than others, but all were affected by what they saw, did, and felt. As Argentinean writer José Narosky said, “In war, there are no unwounded soldiers.” Becoming callous to the death and destruction of battle did not mean that soldiers were impervious to its effects. Men had to overcome and reverse their cultural understandings of killing other men to be effective soldiers; for many men it was easier to die than to kill. Men feared dehumanization; feeling like machines could help them withstand battle, but feeling desensitized or disposable was not comfortable. Soldiers came to realize that there were limits to courage, including the fact that it would not protect them from harm. Men realized their own vulnerability and knew their chances of wounds, death, and survival. This acceptance of war’s reality could turn a soldier bitter and hopeless, leading some to varying degrees of depression. Soldiers could concentrate on their task during battle, taking advantage of the “hardening” process, but they still witnessed horrible things and reacted to them.

Lt. Col. Dave Grossman’s modern study of warfare, entitled On Killing, points to a combination of fear for life and safety, physical exhaustion, the horror of their situation, facing the hate and aggression of fellow human beings, a steady decrease in a man’s “well” of inner strength and fortitude, and the burden of killing others in creating a psychiatric casualty. In this, he argues, fear for personal safety is far outweighed by the burden of killing other men, an act which goes against human nature and cultural constraints. Following orders, acting within a group (which diffuses responsibility), and creating physical and emotional distance with the enemy assist soldiers in the act of killing, but in the aftermath they must come to terms with their actions. The larger the resistance overcome in the act of killing, the more trauma may be experienced. Another large factor studied by Grossman is the concept of fortitude; soldiers can draw on inner strength to sustain them through war and battle, but there comes a point when that well runs dry. It is at that point that a soldier may break, and many become psychiatric casualties of some sort.

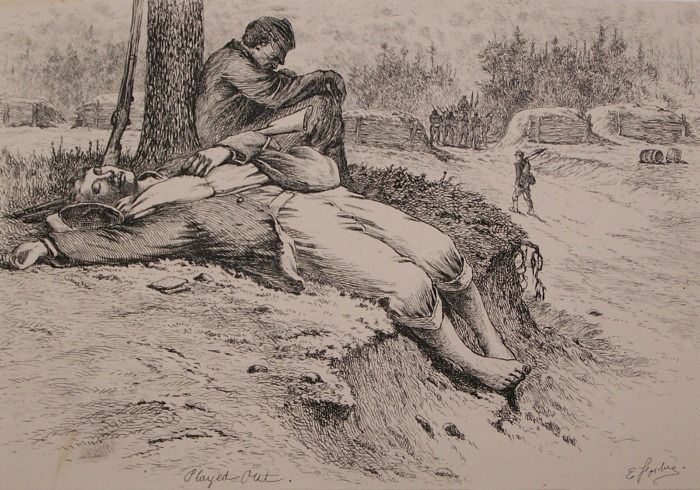

A soldier’s own words often betrayed the fact that his experiences affected him even after “hardening” and having time to acclimate to combat and soldier life. Without an official diagnosis or complete understanding of trauma soldiers used terms such as “the blues,” “lonesome,” “disheartened,” “downhearted,” “discouraged,” “demoralized,” “nervous,” “played out,” “used up,” “anxious,” “worn down,” “worn out,” “depressed,” “rattled,” “dispirited,” “sad,” “melancholy,” and “badly blown” to describe what they were feeling, stemming from a variety of causes. For example, “the blues” could result from the boredom of camp, disease, separation from home, inclement weather and sometimes battle. Cavalryman Henry C. Meyer referred to feeling blue several times in his memoirs; after the Second Battle of Manassas he stated “We all felt rather blue over the loss of comrades in the affair the night before, which had seemed to us so needless,” and after an engagement at Aldie he said, “That night was rather a blue time for us.” “Demoralized” and “rattled” were most often used when describing the mental collapse of an individual or group while “badly blown” referred primarily to physical collapse with occasional references to mental issues.

Despite the murky definitions given by the language used by soldiers, historian Eric Dean has argued that many of these soldiers suffered from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. According to Dean, PTSD, while given that name only after Vietnam, was seen in earlier wars under different definitions, such as “nostalgia,” “combat fatigue,” and “shell shock.” Though using modern terms and definitions in the context of the Civil War may be anachronistic, Dean demonstrates the existence of mental trauma in Civil War soldiers. One example is the case of John Bumgardner of the 26th Indiana Light Artillery, who was knocked down by the concussion of an exploding shell. Recovering himself he was shaken and pale and became morose and sullen for several weeks, in addition to suffering fits of trembling. He would talk about fighting and yell about the enemy approaching when there was no combat present; he was finally sent to an insane asylum in Kentucky.

In some cases, connections to specific symptoms associated with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder are evident in cases of Civil War soldiers; for example, one symptom of PTSD is reexperiencing trauma through instances of flashbacks or nightmares. James O. Churchill wrote that he would be haunted by a recurring nightmare about his Civil War service: “I would be in battle and charge to the mouth of a cannon, when it would fire and I would be blown to pieces.” The case of Albert Frank, fighting around Bermuda Hundred near Richmond, VA, is more severe. While offering the man next to him a drink from the canteen around his neck, the other soldier was decapitated by a shell. That night Frank began to act strangely, running over the breastworks toward the enemy where his fellow soldiers found him huddled, and making shell sounds followed by saying “Frank is killed.” His comrades had to restrain him and eventually sent him to a hospital in Washington under a declaration of insanity.

It did not help that Civil War doctors did not have a good understanding of mental stress and trauma. The Union army recognized insanity as grounds for discharge or exclusion; however, there were no exact guidelines to inform these decisions because more exact diagnoses of insanity would not come until the late nineteenth century. They were, however, becoming aware of the concept of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Prior to the war doctors noticed that victims of railroad accidents experienced “nervous shock” and “hysteria,” fear of the place of the accident, sleeplessness, mental depression, loss of energy, stuttering, loss of sexual desire, contraction of the visual field and sleep disturbances, a condition they labeled “railway spine.” With the rise of “scientific medicine” in the nineteenth century, moving away from pragmatic or religious explanations, doctors struggled to find the physical changes in the nervous system that would explain these symptoms and be consistent with exact scientific principles. With more study and changes in the theory of treating the mentally ill, the idea began to emerge that the brain was the seat of mental illness and that the symptoms of “railway spine” might be psychological.

These theories did not all translate to the Civil War military in which policies focused on maintaining manpower in the field. Many officials were convinced that any man seeking medical attention or discharge due to a mental or physical disability was a shirker who should be returned to duty. Likewise, doctors saw it as their duty to return shirkers to their units and were on the lookout for feigned insanity in the men seeking their attention. Those who did exhibit physical signs of mental trauma were treated for the physical symptoms; if the doctor found “nothing wrong” the men were treated like malingerers. In reality, some, if not many, of these cases may have been recognized as psychiatric casualties from a modern view. However, in the conditions of the Civil War it could be very difficult to tell exactly what a patient was suffering from, whether illness, psychological stress, exhaustion, or a combination of factors.

When faced with blatant cases of mental trauma, doctors struggled to define them without an official diagnosis. Picking up on antebellum definitions, they saw suicide as a result of “insanity” rather than a rational mind. Like the soldiers themselves, doctors had to find words to express what they were seeing in patients, creating four major categories: “insanity,” “nostalgia,” “irritable heart,” and “sunstroke.” Insanity could mean rejection from military service or, if already a soldier, admittance into a hospital and/or discharge. This category could be exhibited in three ways: “mania” referred to exhibited agitation or anxiety that could not be attributable to a cause such as a physical symptom or fever; “melancholia” defined depressed or lethargic behavior; and “dementia” was reserved for soldiers who demonstrated a mental deterioration or disordered mental process. The second category, “nostalgia” or “homesickness,” was primarily a type of mental deterioration in soldiers far away from home, but it occasionally described post-combat conditions as well. “Trotting heart” did not necessarily pertain to combat experiences, but resulted from exhaustion caused by long periods of exertion. The final category, “sunstroke,” was employed similarly to the modern use of “combat fatigue” to reference men who broke down in battle.

The policy on military discharges was to maximize manpower in the army, even if soldiers exhibited signs of mental stress. Discharges for insanity could be made only for “manifest” conditions and approval had to be obtained by both the soldier’s commanding officer and unit medical officer. However, by 1863 a medical officer in the field could not discharge a man on the basis of insanity; instead, these men went to the Government Hospital for the Insane in Washington, DC where they could be observed by experts. Only about 1,231 men were treated at the Government Hospital for the Insane; the records available for these cases show soldiers who had broken down in battle, gone berserk, or deserted. Most soldiers facing mental stress never made it to Washington. In addition, soldiers suffering from “manifest” insanity and other severe disabilities were not eligible for the Invalid Corps (later renamed the Veteran Reserve Corps), which took men who could no longer fight on the front lines and gave them other duties, such as guard duty, garrison duty, and hospital positions. Instead, some were treated in the field or sent to asylums throughout the states. They were sent from both camp and battlefield for causes ranging from exposure, fear before battle, war excitement, “shock of battle,” and the explosions of shells to “fatigue,” “sunstroke,” and “overexertion.” In some cases, if comrades noticed a man who was unable to perform his duties they kept the afflicted in camp, gave him lighter duties, and excused him from combat. Soldiers sometimes took their removal from combat into their own hands, straggling behind, helping a wounded comrade to the rear, or resorting to the more extreme actions of mutiny or self-mutilation. Desertion was another way some men may have sought to remove themselves from the army once they realized they could no longer manage the mental stress; deserters often flew under the radar or remained quiet about their reasons for leaving, but some cases show that mental issues could have been a cause of some desertions.

For more on the experience of soldiering, read Experiencing the War: The Soldier's View

Kathleen Logothetis Thompson graduated from Siena College in May 2010 with a B.A. in History and a Certificate in Revolutionary Era Studies. She earned her M.A. in History from West Virginia University in May 2012. Her thesis “A Question of Life or Death: Suicide and Survival in the Union Army” examines wartime suicide among Union soldiers, its causes, and the reasons that army saw a relatively low suicide rate. She is currently pursuing her PhD at West Virginia University with research on mental trauma in the Civil War. In addition, Kathleen has been a seasonal interpreter at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park since 2010 and has worked on various other publications and projects.