Scapegoat or Scandal? J.E.B. Stuart and the Battle of Gettysburg

/The June 12th, 1863 edition of the Richmond Examiner seethed. Just days before, Confederate cavalry had been caught completely by surprise in a daring strike by their Union counterparts at Brandy Station Virginia, and only after a hard fight with the help of Southern infantry was the enemy repulsed. “But this puffed up cavalry of the Army of Northern Virginia,” the Examiner crowed, “has been twice, if not three times, surprised since the battles of December, and such repeated accidents can be regarded as nothing but the necessary consequences of negligence and bad management.” Such humiliations were unacceptable, and the Examiner concluded by charging that better organization, more discipline, and greater earnestness among “vain and weak-headed officers” was needed. Other Southern papers offered more of the same. The Richmond Sentinel called for greater “vigilance…from the Major General down to the picket.” The Charleston Mercury thought the affair an “ugly surprise,” while the Savannah Republican thought it all “very discreditable to somebody.”

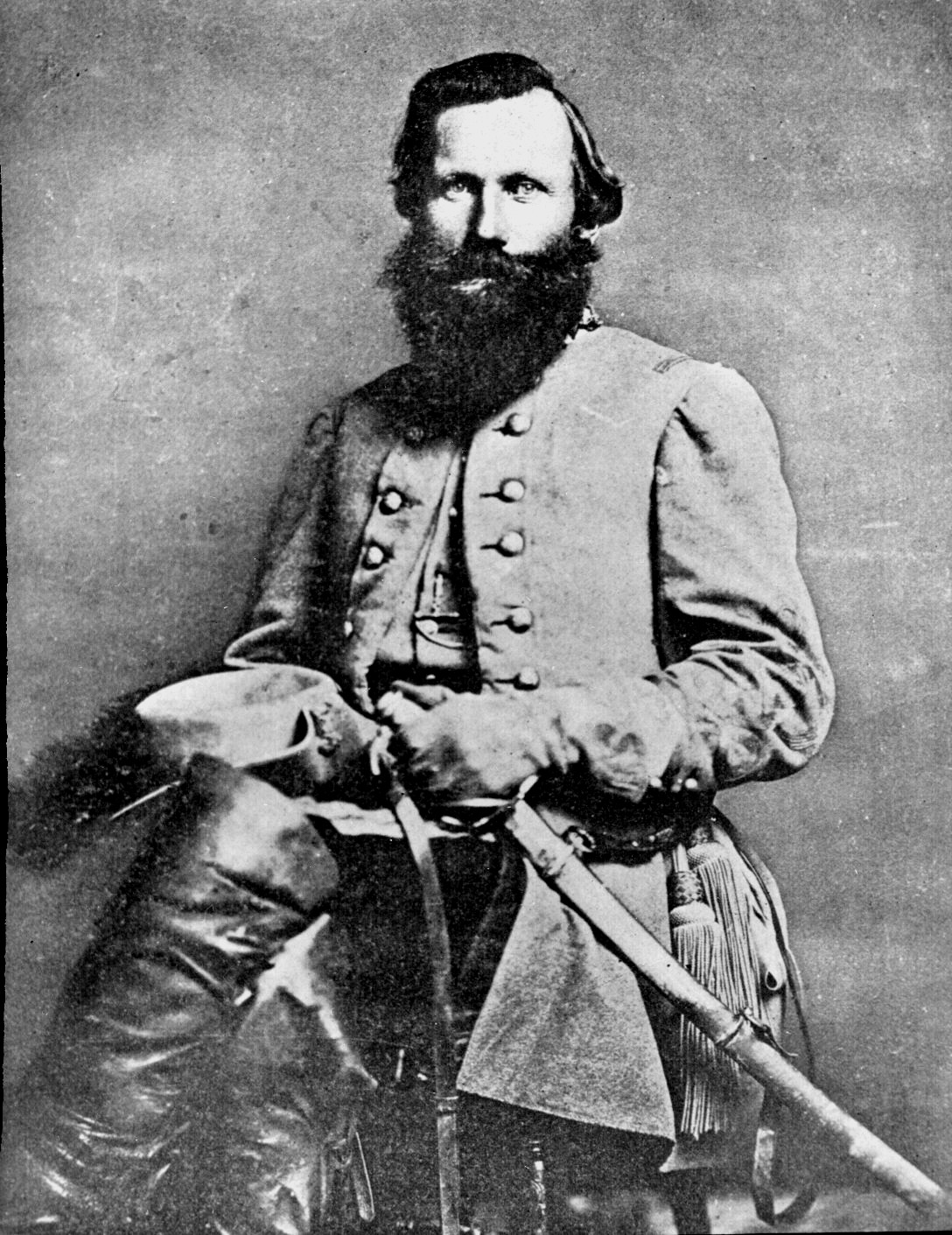

The commander of Confederate cavalry, James Ewell Brown (Jeb) Stuart, had to be wondering if the Brandy Station fight wasn’t “discreditable” to him. Having risen to command by superb leadership during the war's first years, the surprisingly tough fight at Brandy Station seemed to stain Stuart's reputation (which he cultivated assiduously). For the troopers underneath him, Brandy Station was “the hardest cavalry fight…since the war began.” The Army of Northern Virginia's cavalry had always enjoyed total domination over its Yankee foe; Brandy Station challenged that assumption.

Soon enough, however, Jeb Stuart and his Confederate troopers would have a chance at redemption. Young Benjamin Parker of the 2nd North Carolina Cavalry, writing to his sister on June 10th, opined that “[Robert E.] Lee I think is going to make a move across the river. There will be some hard fighting pretty soon.” The young Tarheel’s intuitions proved correct. Indeed, Confederate soldiers were already pounding the roads north, headed for the small Pennsylvania hamlet named Gettysburg. The Confederate cavalry would soon be trotting north as well, in search of glory and perhaps redemption.

Throughout June, the Army of Northern Virginia snaked north in the valleys west of the Bull Run and Blue Ridge Mountains, headed for Maryland and Pennsylvania beyond. It was Stuart’s duty to screen these movements with his 10,000 troopers, divided into five brigades. By mid-June he was off to an excellent start. Throughout mid-June, at the minor battles of Aldie, Middleburg, and Upperville respectively, Stuart’s horsemen successfully repulsed probing Union troopers hoping to confirm the location of Lee’s army. The combination of the Bull Run Mountains and Stuart’s cavaliers kept the Union Army of the Potomac in the dark; Lee’s move north remained a secret.

As Lee’s army approached Maryland, the time arrived for Stuart’s role in the upcoming campaign to be laid out. In a pair of orders on June 22nd and 23rd, Lee outlined his objectives for Stuart. The cavalry commander was to leave at least two brigades to continue securing the mountain passes as the army moved north. Stuart could take the remaining three brigades, however, through Maryland and “take position on General [Richard S.] Ewell’s right, place yourself in communication with him, guard his flank, keep him informed of the enemy’s movements, and collect all the supplies you can use for the army.”

The stain of Brandy Station still lingering, Stuart hoped to carry out these new orders in dramatic fashion. Twice before in the war he had ridden his troopers all the way around the Union army, to their chagrin and his glory. Stuart felt convinced he could circle the Union army yet again. Conferring with the “Gray Ghost” John Mosby, Stuart felt confident his men could ride around the Yankees to unite with Ewell; a perfect remedy to Brandy Station. In Lee’s order, it was left to Stuart to “judge whether you can pass around their army without hindrance, doing them all the damage you can.” With a wide amount of discretion, Stuart could move north as he chose, as long as he guarded the Blue Ridge passes and kept in touch with General Ewell. Stuart’s fate in the upcoming campaign rested in his own gloved hands.

Jeb Stuart elected to ride around the Union army. To ensure the army remained protected, Stuart left behind two brigades of cavalry under Beverly Robertson and William “Grumble” Jones, known both for his temper and his skill in commanding detachments. A brigade of troopers under Albert Jenkins would be at Lee’s disposal as well. All in all, nearly five thousand cavalrymen would stay with the Army of Northern Virginia. Satisfied that Lee was well-taken care of, Stuart took his remaining three brigades under Wade Hampton, Fitz Lee, and John Chambliss and started off on his grand raid, sure that glory lie ahead.

Riding out on June 25th, Stuart begin to immediately encounter troubling signs. Attempting to move east through Glasscock Gap in the Bull Run Mountains, Stuart discovered the path blocked by Federal infantrymen; Stuart’s horse artillery failed to move them. Moving south, Stuart discovered only more Yankee columns. The enemy was on the march and blocking Stuart’s path. Stymied, Stuart could not move east until the next day. Lee’s orders allowed Stuart to pass around the enemy if there was “no hindrance.” Whether these north-bound Yankee columns constituted a hindrance is debatable, but it no doubt delayed Stuart.

The next two days brought Stuart better luck. Continuing south, Stuart found a way east all the way to Fairfax Court House in central Virginia, where on the 27th they encountered a small body of the enemy under the 11th New York Cavalry. Charging forward under the lead of Wade Hampton, the 1st North Carolina Cavalry cleared the Federals out and secured a large supply of stores. At this time, Stuart scribbled off a message to Robert E. Lee, informing him of his location, the captured goods, and the northward movement of the Union army. That message never reached General Lee.

Turning north himself, Stuart’s troopers reached the swollen Potomac and crossed into Maryland. To keep their artillery shells dry, the Rebels “carried them in our hands” across the river. William Blackford recalled the reaching Maryland’s shore joyously; “Oh, what a change! From the hoof-trodden, war-wasted lands of old Virginia to a country fresh and plentiful.” Fresh and plentiful was right; the men were rewarded on the morning of the 28th with the pleasure of destroying several Chesapeake and Ohio Canal barges filled with food. Private John Armstrong of the 4th Virginia Cavalry remembered “filling my haversack with salt herring.”

At this point, Stuart had crossed the Potomac and uncovered the enemy’s movements (although unbeknownst to him, his courier had not reached Lee). He had captured a variety of goods, destroyed enemy property, and generally made a nuisance of himself. Yet all of this came at a cost. He was now approximately eighty miles southeast of the Confederate army, and the Federal army stood between him and Lee. He had yet to link up with Richard Ewell’s corps as his orders dictated. Worse, his ability to communicate with Lee was circuitous and precarious at best. Robert E. Lee, in turn, was “surprised and disturbed” to learn on June 27th that Stuart and his troopers were still in Virginia. Lee ordered scouts to try and locate his lost general. There was a growing, uneasy disconnect between Lee and his cavalry commander.

Jeb Stuart having crossed the Potomac, he found himself at a crossroads. Instead of turning northwest to attempt to unite with Lee and Ewell, he decided to continue his raid and turn east. Moving to Rockville, a Washington D.C. suburb, Stuart captured 125 Union supply wagons, loaded with food, hay, bread, bacon crackers and more. Thinking in bigger terms, Stuart contemplated then dismissed the possibility of striking Washington itself. Having by now captured nearly 400 Union prisoners up to this point, Stuart took some time to parole them, then plodded northward with his newly captured wagon train throughout the rest of the 28th and 29th. The splashier his raid, the further away Brandy Station seemed.

On the 29th, while his men cut telegraph wires and tore up the tracks of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, Stuart discovered that the enemy was in Frederick, Maryland. The move seems to have jolted Stuart, who realized the sudden importance of uniting with Lee “to acquaint the commanding general with the nature of the enemy’s movements…” Finally, Stuart recognized just how serious the Union movements were, and just how imperative his presence with the Army of Northern Virginia had become.

Clashing with Yankee cavalry at Westminster on June 29th, Stuart and his men entered Pennsylvania the next day. They nearly ran into disaster. The lead elements of Stuart’s column and a single brigade of enemy cavalry nearly ran into one another outside of town. Taking the offensive, several of Stuart’s Virginia and North Carolina regiments charged ahead, only to be met with a vicious counterattack. In the wild retreat, Stuart and his staff were nearly captured, escaping only by leaping a fifteen-foot-wide gully. The Federals, content with their little victory, didn’t pursue.

With most of his troopers guarding the long wagon train, Stuart was unable to mass a large enough force to dislodge the enemy, and instead had to find another way north. The men were tired, “broken down and in no condition to fight” as one officer reported, and the wagon train slowed Stuart’s column down. Plodding northward, by July 1st Stuart's tired troopers were resting in Dover, Pennsylvania. The Battle of Gettysburg was beginning blindly, and Jeb Stuart was miles away. Animals and men alike were exhausted. Writing home, a North Carolinian confessed, “I thought I knew some thing of the hardships of a soldier’s life but must confess that I did not.”

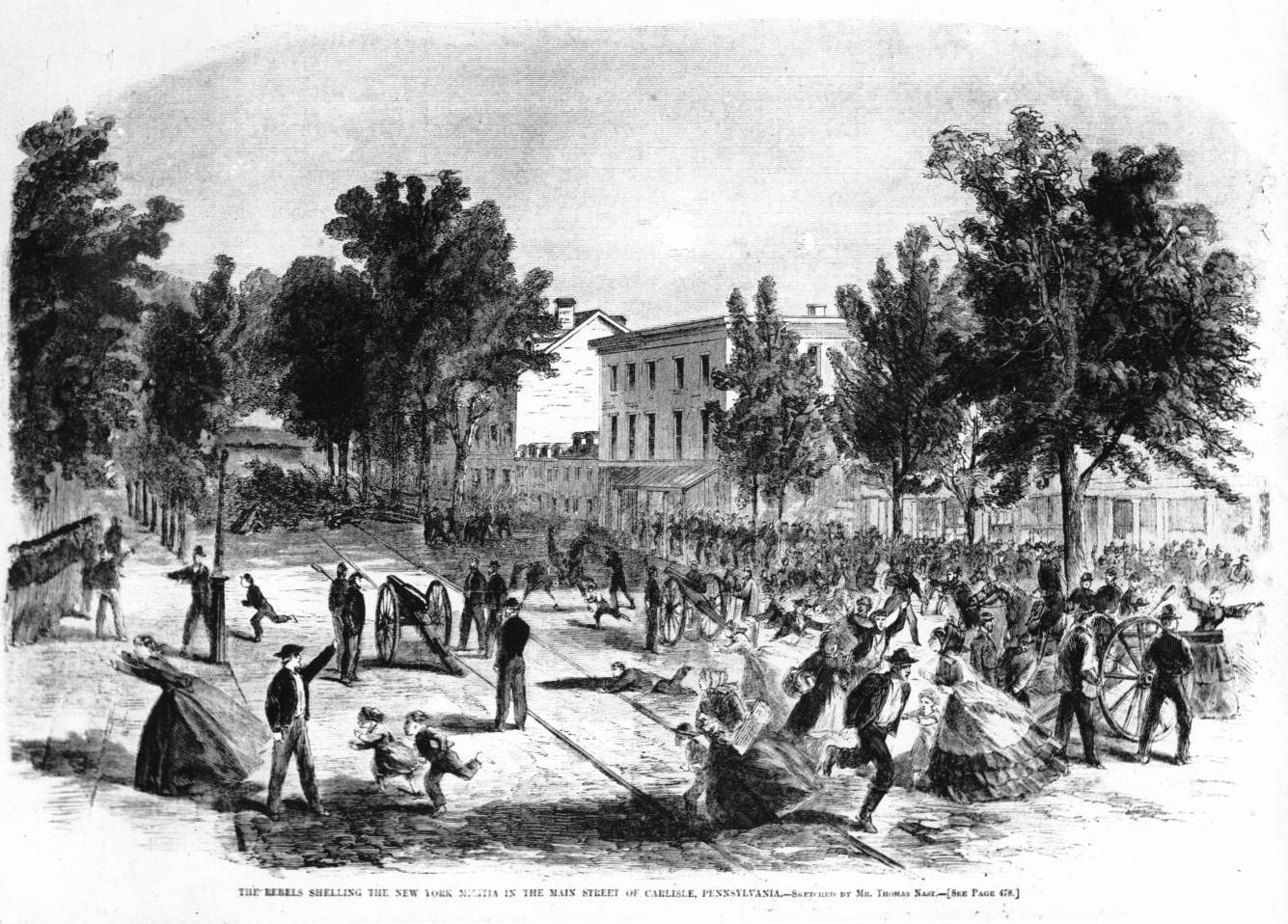

By now, Stuart was actively searching to unite with Ewell, but didn’t know where to find him. Believing Ewell to be in Carlisle, Stuart set off for that town, only to discover that it was occupied not by Ewell but instead 2,400 Union militiamen. Threatening to shell the town if the Yankees didn’t surrender, “shell away and be damned!” came the reply. So shell away Stuart did, opening fire on the town. The Confederates were so exhausted that many of the troops slept through the bombardment.

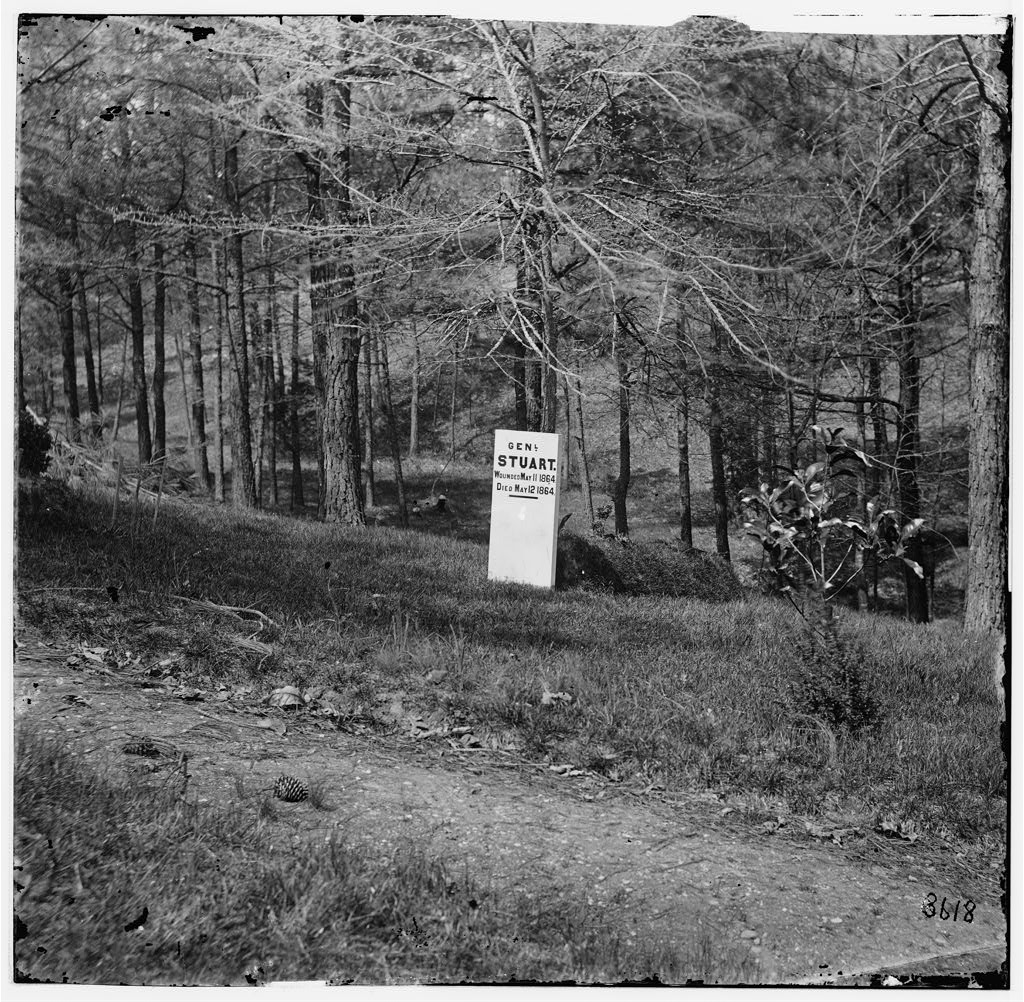

Meanwhile, Robert E. Lee, only thirty miles away, remained unsure of Stuart’s whereabouts. Inquiries to subordinates brought only disappointment. An aide overheard Lee grumble that “Gen’l Stuart has not complied with his instructions.” Finally, one of Stuart’s riders located Ewell’s corps in Gettysburg, and returned to Stuart with orders to march for the town. This was the first communication that Stuart or Lee’s army had with one another since June 25. In that time, the Army of Northern Virginia had blindly moved north and found itself unwittingly trapped in an engagement at Gettysburg.

In the morning hours of July 2nd, Jeb Stuart made his way to General Lee. “Well, General Stuart,” Lee said simply, “you are here at last.” However muted, the rebuke no doubt stung. Stuart and Lee’s conversation was, according to an aide, “painful beyond description.” Regardless, Stuart had arrived, as did most of his tired troopers throughout the day. Stuart spent the July 2nd familiarizing himself with the ground, for he had new orders to guard the Confederate left and strike the Union right. Thus, Jeb Stuart and his men took their position, ready to participate in the final, climactic day of battle at Gettysburg.

On July 3rd, 1863 some 14,600 grad-clad Confederate infantrymen belonging to the divisions of Generals Pettigrew, Trimble, and George Pickett made one of the greatest charges in American history. Crossing nearly a mile of open ground, their attack was aimed at the center of the Union line, an arrow shot at the Army of the Potomac’s heart. It was the role of Jeb Stuart’s troopers, reinforced by Albert Jenkins and numbering some 3,500, to strike the Union far right while this attack was being made. If Pickett’s great charge was successful, there was hope that Stuart would be in position to exploit the breakthrough and cut-off lines of retreat.

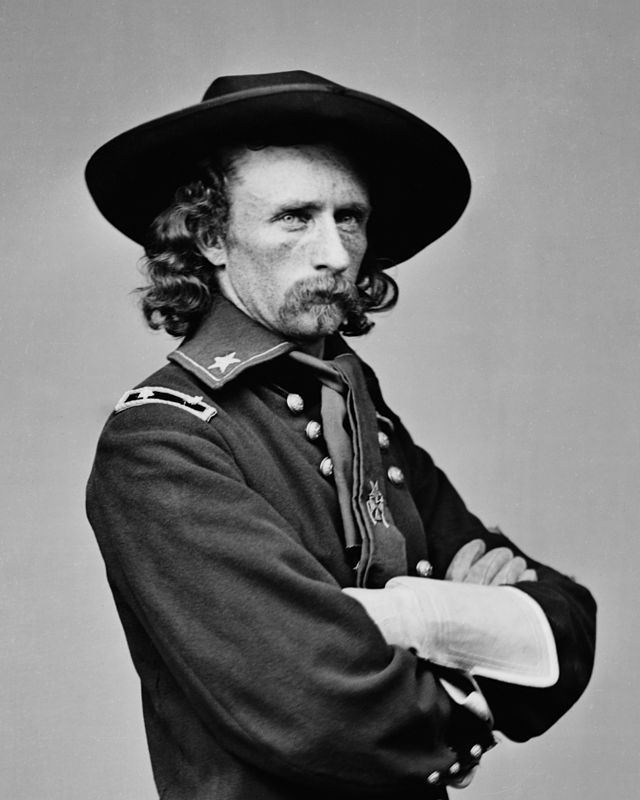

Jeb Stuart rode out to battle with four brigades of cavalry, those of Wade Hampton, Fitz Lee, John Chambliss, and Milton Ferguson (replacing a wounded Albert Jenkins). Having moved directly behind the Union army, the Confederate cavalry would need to vanquish their Federal counterparts before they could assault the Union rear or support any breakthrough made by Pickett’s charge. And the Federals were there to greet them; three brigades of cavalry under David Gregg, John McIntosh, and the flamboyant George Custer. For the first time since Brandy Station, the Union and Confederate cavalry forces squared off against one another.

Jeb Stuart decided to place his men along Cress’s Ridge, a fairly steep rise several miles east of Gettysburg. Ferguson’s troopers were on hand and took their place along the ridge; the rest of the brigades were ordered to join them. It was now roughly eleven o’clock, and back on Seminary ridge nervous infantrymen waited in the woods while dozens of artillery pieces prepared the opening bombardment of Pickett’s charge. Indeed, shortly after taking the ridge, “the most terrible cannonading of the war occurred,” wrote one Rebel trooper. The battle was shaping up at Gettysburg, and it was shaping up in front of Stuart on Cress’s Ridge as well.

George Custer and his Michigan troopers aggressively challenged the Rebels' position, throwing out a skirmish line that was soon supported by horse artillery. Stuart’s own guns attempted to reply, but the Federals seemed to have the better of it in the duel. “The Federal artillery seemed very effective,” a Confederate officer lamented, “while ours seemed to be of little service.” Skirmish lines swayed back and forth as each side marshaled its brigades for the coming fight.

Stuart struck first. The 1st Virginia Cavalry, whom Stuart had once personally commanded, charged down the ridge and shattered the enemy’s skirmish line. As the Virginians took command of the field, Custer quickly responded, personally leading the 7th Michigan in a cavalry charge. “Come on, you Wolverines!” the young brigadier general cried. The two bodies of mounted horsemen collided, sabers slashing and the sharp crack of pistols and carbines piercing the air. Although temporarily driven back, Stuart poured more men into the fray. “The battle grew hotter and hotter,” wrote a private in the 3rd Virginia Cavalry, “horses and men were overthrown or shot and many were killed and wounded.”

At this critical moment, Wade Hampton’s troopers plowed forward into the fight at a full gallop. The thundering Rebels, whose “saber blades dazzled in the sun,” were met by a reciprocal charge from, yet again, George Custer. The collision, to one Yankee trooper, like “the falling of timber…so sudden and violent.” In the middle of the melee, Hampton himself was wounded. Finding himself trapped against a fence and attempting to stave off three attacking Yankees, Hampton was shot in the back. Unwilling to lie down his sword, Hampton turned to the assailant in his rear and growled out, “You dastardly coward—shoot a man form the rear!” and began to cut his way out of the scrap.

As Hampton fell back, so did many of his men. Soon all the Confederate troopers were retreating back to the security of Cress’ Ridge. Confederate casualties numbered 181; the Federals suffered 254 casualties, most of them unsurprisingly from Custer’s command. The fight was over and lost. Confederate infantry assaulting Cemetery Ridge had fared no better. What had begun at Brandy Station—an embarrassment by the enemy and an inkling that things were changing—was confirmed at Gettysburg. Union cavalry could and would fight; the days of Southern dominance were over. Indeed, that held true for both armies in general; Gettysburg signaled a primal shift in the war, a recognition that even more tough, blood-stained roads lie ahead.

As Lee and his defeated army began their retreat southward, Stuart’s troopers, fatigued from nine days of raiding topped by a climactic battle east of Gettysburg, could not afford to rest. They were charged with covering the Confederate retreat, guarding supply trains, and holding the enemy at bay. This they did well. Despite occasional limited successes by the enemy and almost daily fighting, the Confederate troopers largely succeeded in protecting the Confederate retreat over the next ten days. By July 14th, the Army of Northern Virginia, along with its mounted men under Stuart, was back in its namesake state. The Gettysburg campaign had come to an end.

Looking across the broad sweep of events, judging Jeb Stuart’s performance isn’t as simple as it seems. Certainly, not all of his objectives were fulfilled. Most prominently, Stuart spent most of the campaign on a wild raid in which he was out of contact with his commander. He never linked up with General Ewell (not in a timely fashion, at any rate), and Lee was not kept appraised of the enemy’s movement. Whatever his raid may have accomplished, it also fatigued his troopers and possibly limited their effectiveness in the final fight on July 3rd.

Yet there are facts which defend Stuart’s course of action as well. Robert E. Lee’s orders to Stuart offered the young cavalier a tremendous amount of discretion; that he utilized that discretion rests at much on Lee’s shoulders as on Stuart’s. Materially, he brought need supplies back to the army, captured hundreds of prisoners, and disrupted the enemies supply line. Nor did his raid leave Lee entirely without cavalry. Although Stuart undoubtedly took some of the finer Confederate troopers with him, the brigades of Beverly Robertson, “Grumble” Jones, and Albert Jenkins were at Lee’s disposal. Lee can hardly be said to be bereft of cavalry when Stuart left nearly five thousand horsemen behind. While Stuart attempted to notify Lee of Union movement north, those messages never got through. Yet the three brigades of cavalry left to Lee could have detected those movements as well.

What ultimately motivated Stuart to take off on his raid? Again, answers don’t come easily. It is hard, however, not to see the battle at Brandy Station as the catalyst that pushed Stuart to undertake his grand raid, however risky. That “discreditable” debacle perhaps spurred Stuart to greater risks in order to repair his tarnished reputation. At least twice, Stuart had chances to abort his raid. On the very first day, Stuart was surprised to discover Yankee infantry blocking his path as it trudged northward. Instead of reporting to Lee and moving up the valley himself, he choose to continue his venture by moving further southeast, lengthening the raid’s duration and his distance from the Army of Northern Virginia. Again when Stuart crossed the Potomac, he could have bolted northwest to unite with Ewell as his orders directed; instead he continued his raid by scaring the Washington suburbs. Stuart pushed the raid to its limits, and the result was that Lee was without his best cavalry commander.

Ultimately, Stuart’s legacy at Gettysburg remains mixed. The raid itself was a mild success, and in accordance with Lee’s orders, but it came at a tremendous cost. Lee, whether by his own fault, the fault of the cavalry at his disposal, or the fault of Stuart, was indeed blind as he moved north into Pennsylvania. When Stuart did arrive, his worn and weary troopers failed to dislodge the enemy cavalry on July 3rd. It cannot be said that Stuart lost the Battle of Gettysburg for the Confederacy, but he certainly affected its outcome in his own search of glory and redemption.

Zac Cowsert currently studies 19th-century U.S. history as a doctoral student at West Virginia University, where he also received his master's degree. He earned his bachelor's degree in history and political science at Centenary College of Louisiana, a small liberal-arts college in Shreveport. Zac's research focuses on the involvement and experiences of the Five Tribes of Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) during the American Civil War. He has worked for the National Park Service at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park. ©

Sources & Further Reading:

Primary Sources

Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park. Bound Volumes.

Benjamin Franklin Parker. Letter. 2nd North Carolina Cavalry. Vol. 206.

Franklin Gardner Walter. Diary and Letters. 39th Virginia Cavalry. Vol. 138.

James W. Gray. Letters; 10th Virginia Cavalry. Vol. 31.

John Edward Armstrong. Autobiography. 4th Virginia Cavalry. Vol. 374.

Wiley C. Howard. “Sketch of Cobb Legion Cavalry.” Cobb Legion Cavalry. Vol. 244.

Secondary Sources

Gorman, Paul R. “J.E.B. Stuart and Gettysburg,” Gettysburg Magazine. No. 1. July, 1989. 86-92.

Longacre, Edward G. Lee’s Cavalrymen: A History of the Mounted Forces of the Army of Northern Virginia, 1861-1865. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2012.

Robinson, Warren C. Jeb Stuart and the Confederate Defeat at Gettysburg. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007.

Sears, Stephen W. Gettysburg. New York: Mariner Books, 2004.

Shevchuk, Paul M. “The Lost Hours of ‘JEB’ Stuart.” Gettysburg Magazine. No. 4. January, 1991: 65-74.

Wert, Jeffry D. Cavalryman of the Lost Cause: A Biography of J.E.B. Stuart. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2008.