In the Shadow of Appomattox: The Significance of Bennett Place

/Yesterday marked the 150th anniversary of the surrender of Confederate General Joseph Johnston to Union General William Sherman. While history focuses on Lee’s surrender at Appomattox as the end of the Civil War, Johnston’s surrender at Bennett Place was significantly larger and demonstrates the lack of a definitive end to the war.

As Appomattox was the end of the famous Overland Campaign between Generals Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee, Bennett Place was the finale of the equally famous 1864 campaign of General William T. Sherman who attacked Atlanta against the force of General Joseph E. Johnston and then swung around to hit the Carolinas. Interestingly, if President Jefferson Davis had his way, Johnston would not have been in charge when the surrender occurred in April 1865. Davis had removed Johnston from command at Atlanta on July 17, 1864, believing that the General had become ineffective as a commander, and Johnston had then moved to Columbia, SC to retire. As Sherman’s campaign continued to steamroll through the South, however, the public called for Johnston’s return to the army and Davis reluctantly reinstated Johnston on February 25, 1865. His command consisted of the remnants of the Army of Tennessee along with two other field armies.

Johnston hoped to coordinate his forces with those of Robert E. Lee in order to take care of Sherman’s army and then return to Virginia to attack Grant. Lee initially did not agree to the plan and Johnston faced Sherman alone, gaining some success at the Battle of Bentonville in March, then retreating to Greensboro, NC in the face of the Union’s larger numbers. Lee then desperately tried to reach Johnston’s army after the fall of Richmond in early April, but he was not able to evade Grant’s Army of the Potomac and surrendered at Appomattox Courthouse on April 9, 1865. With news of Lee’s surrender followed by the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln a few days later, Johnston agreed to meet Sherman for negotiations.

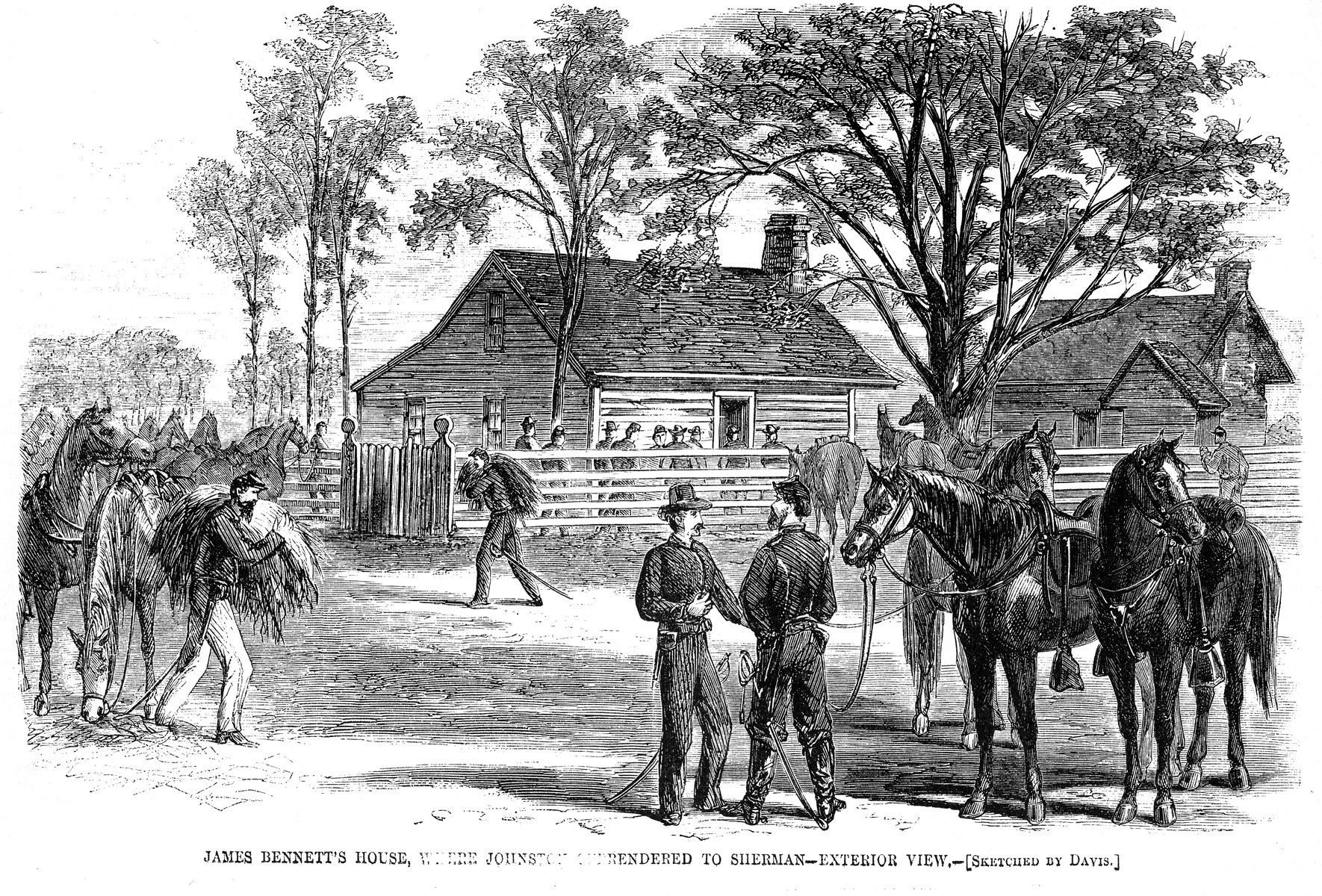

The dispatches between the two generals over Easter weekend, led to a series of negotiations on April 17, 18, and 26. Sherman and Johnston agreed to terms on April 18, advised by both General Ulysses S. Grant and General John Breckenridge, and sent them to their respective governments for approval. Sherman’s initial terms overstepped his boundaries a little as he went past the terms Grant had given to Lee and included terms that would address a general end to the war and the beginning stages of Reconstruction. These terms were not approved by the US government, and, in the end, Johnston surrendered on April 26th on terms similar to those at Appomattox.

Johnston surrendered 89,270 soldiers at Bennett Place, the largest surrender of the war. This action proved to be a final stage in peace negotiations; in the weeks and months afterwards small engagements and surrenders would continue to take place, but the majority of Confederates were no longer active in the field. In terms of numbers, Bennett Place overshadows Appomattox and it brings a finality to the conflict that Appomattox does not. However, Lee’s popularity was much greater than Johnston’s and Lee’s surrender was a moral blow to the entire Confederacy, leading to many of the following surrenders (including Johnston’s). Taken together, both Appomattox and Bennett Place ended the significant military resistance to the Union army in the South, but Johnston’s surrender also demonstrates that the end of the war was never cut and dry. While Lee’s surrender is seen by many as the “end of the war,” there were still active Confederate armies in the field. And, while Johnston’s surrender removed a large number of Confederate soldiers from active service, there remained smaller forces that would still need to surrender to the now inevitable defeat of the Confederacy.

Further Reading:

Mark L. Bradley. This Astounding Close: The Road to Bennett Place. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2000.

Kathleen Logothetis Thompson graduated from Siena College in May 2010 with a B.A. in History and a Certificate in Revolutionary Era Studies. She earned her M.A. in History from West Virginia University in May 2012. Her thesis “A Question of Life or Death: Suicide and Survival in the Union Army” examines wartime suicide among Union soldiers, its causes, and the reasons that army saw a relatively low suicide rate. She is currently pursuing her PhD at West Virginia University with research on mental trauma in the Civil War. In addition, Kathleen has been a seasonal interpreter at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park since 2010 and has worked on various other publications and projects.