Caught in the Crossfire: Civilians at Fredericksburg

/In December 1862, the city of Fredericksburg found itself in the crossfire of the armies of Lee and Burnside. For several months that summer, residents were forced to deal with the indignities and inconveniences of living in an occupied city. Now the Union army was back once more and this time General Robert E. Lee and his army were in place to contest their presence. With armies on either side of it, Fredericksburg braced itself for the storm.

On November 21, 1862, General Ambrose Burnside demanded the surrender of the town with the explanation that shots had been fired at his army. Townspeople avoided surrendering, and the threatened artillery barrage, by arguing that the shots had been fired by Confederate military personnel, not residents. They assured the Burnside that it would not happen again and promised that Lee would not occupy the town or use it for military purposes. At the same time, however, Lee issued orders for women, children, and invalids to leave town immediately. Many Fredericksburg residents heeded the warning, packed up whatever belongings they could, and left their homes.

These refugees scattered in all directions from the city. Some residents used the railroad to move south to Richmond, Petersburg, or Charlottesville. Many stayed with family members or friends in the country, or sheltered in barns, churches, and outbuildings. Several families sought the charity of complete strangers. Mathilda Hamilton wrote that “[t]he house is as full as it can be, and all our outhouses full. Respectable white people, with their own provisions are refugeeing in our servants houses, and all about in the neighborhood it is the same way.” Some huddled under tents in make-shift camps, braving the December weather the best they could. One such camp was located on the opposite side of Marye’s Heights, behind the Confederate line and another was located at Salem Church where:

All was bustle and confusion. I suppose there were several hundred refugees there. Some were cooking outside in genuine gypsy fashion, and those who were infirm or sick were trying to get some rest in the cold, bare church. The leafless trees, through which the winter wind sobbed mournfully, the scattered groups seen through the smoke of numerous fires, and the road, upon which passed constantly back and forth ambulances and wagons full of wounded soldiers, presented a gloomy and saddening spectacle. (Fanny White)

After the initial threats and excitement, there was little movement by the Union army. General Burnside was waiting for pontoon boats to arrive before advancing across the Rappahannock River. When there was no fighting for two weeks, many refugees returned home. It was a bad decision to make and the crack of two signal guns in the early morning hours of December 11, 1862 warned them that the worst was at hand.

The two shots fired by Confederate guns warned the army that the Union crossing had begun. Mississippi soldier in the homes and buildings along the river contested the bridge building operations, firing at the Union Engineers struggling to construct the pontoon bridges across the river. Consequently, Burnside ordered an artillery bombardment of Fredericksburg to drive the Confederates from the houses. This act began the large scale destruction of the city. For much of the afternoon, 150 Union guns fired on the town, damaging or destroying most of the structures. Confederate artillerist E.P. Alexander estimated that more than 100 shells were fired per minute on the city.

The flash of one cannon after another as they were arranged along the hills beyond, lighting up the scenery around, and the deafening shouts that followed, were sights and sounds which the novel spectator must have viewed and listened to with eager eyes and ears. It was a beautiful but awful sight.

In the streets the confusion was dreadful. Here, a child was left, its frantic mother having fled; and there a husband, who, in the excitement of the moment, had become separated from his wife, ran madly about in search of her while she was being safely conveyed from the scene of terror on a wood cart. Here, families were crouching in their dark cellars for protection from the ruthless shells; while there, the more reckless ascended to the house-top to view the impossible grandeur of the scene before the daybreak. (Mamie Wells)

Those residents who had stayed in town or returned to their homes were caught in the middle of the bombardment. Hurrying to cellars and basements, families and slaves huddled together as shells tore through their houses. From early morning until mid-afternoon Fredericksburg residents bore the brunt of Union artillery. Some families fled in the midst of the bombardment, becoming refugees again. Jane Beale’s family was rescued from their cellar with the help of an ambulance borrowed from the army and Fanny White with family and others who sheltered with them hurried away from their home only partly dressed:

They urged my mother to take her children and fly at once from the town. After resisting until the gentlemen in despair were almost ready to drag her from her dangerous situation, she finally consented to leave. The wildest confusion now reigned…but the gentlemen insisted so that we had only time to save our lives, that they would not even let my mother go back into the house to get her purse or a single valuable. So we started just as we were; my wrapping, I remember, was an old ironing blanket, with a large hole burnt in the middle. I never did find out whether Aunt B. ever got her clothes on, for she stalked ahead of us, wrapped in a pure white counterpane, a tall, ghostly looking figure, who seemed to glide with incredible rapidity over the frozen ground.

A few families were forced out of their homes, such as the eighty year old postmaster, Reuben Thom, and his family who had to escape the flames when shells set their house on fire. At least fifty structures were destroyed by fire during the course of December 11th. A few civilian lives would be lost as well, although the details are sketchy. Eighteen year old Jacob Grotz was apparently killed by an exploding shell and an African-American woman was also killed by a shell as she huddled under her bed.

Another civilian would become a casualty after the first Union troops had crossed the river and were endeavoring to empty the town of Confederates, moving house by house, street by street. Captain George Macy of the 20th Massachusetts placed an old man found in one of the houses in front of his troops as a guide to lead them through the streets of Fredericksburg. In the fierce crossfire of the street fire, the guide soon dropped dead, killed by Confederate fire. By nightfall, the Confederates had pulled out of town and Union soldiers poured over the river on the now-completed bridges. Officers took private residences as their quarters and soldiers bunked down among the ruins of houses.

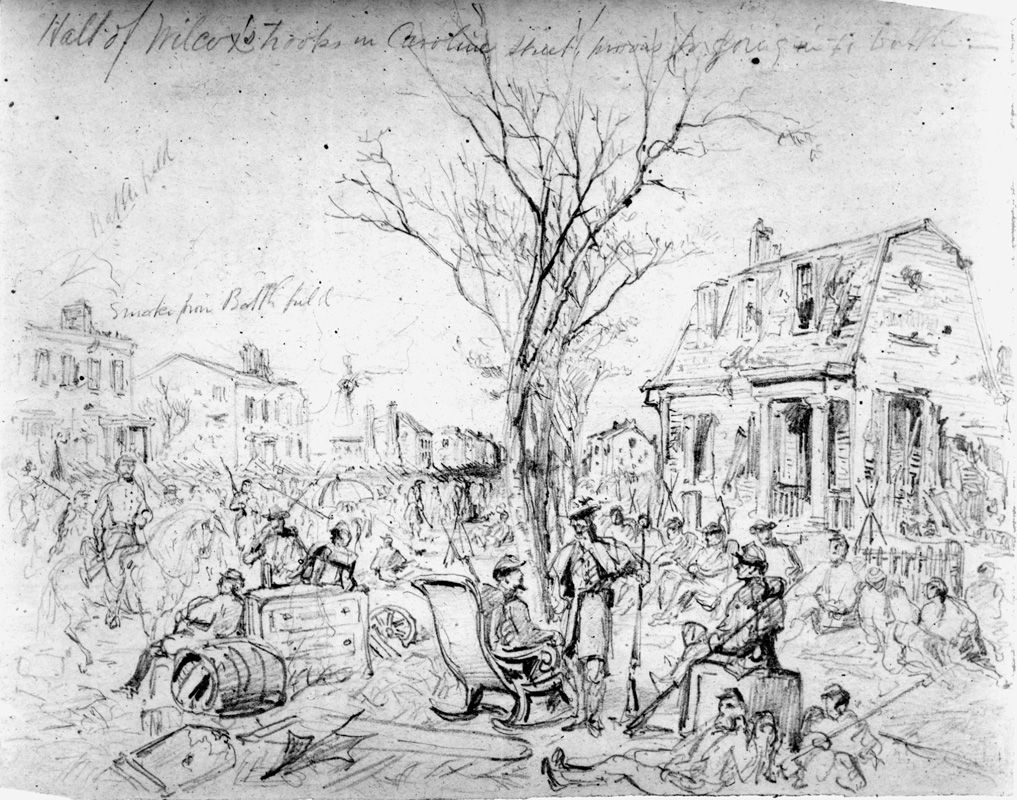

December 12th was a day of little fighting between the two armies, giving the Union soldiers time to roam the city of Fredericksburg. Many found the abandoned houses too tempting and took supplies and souvenirs. Petty thieving soon escalated into full-scale looting and wanton destruction. Soldiers stole what they wanted and destroyed everything else that they could not use. Furniture was dragged into the streets and men lounged about as if at home or broke up the pieces for firewood. Precious family heirlooms, china, paintings, mirrors, all were destroyed. Men invaded the most private spaces of homes and emerged decked out in women’s dresses and undergarments, frolicking in the streets in their weird attire. The destruction was a marked shift in policy towards civilians. Previously Union armies took great care to protect private property, now they destroyed it at will. “They deserved it all for there is not a stronger secession city in Virginia than Fredericksburg,” wrote one soldier and another mused, “[d]o our friends cry out against this? So do we—it is wrong, essentially wrong, but it is War.”

Few civilians remained in town during the battle, but for those who remained the sights and sounds of December 13th were as bad as what had come before. Mamie Wells, trapped in her basement with the rest of her family, watched the lines of Union men march past the window towards Marye’s Heights:

At each charge the roar of musketry—that soul-sickening sound—had the effect of almost stopping my breath. In those moments I pictured to myself the dead and the dying, and wondered why such a cruel thing as war should ever be allowed in a civilized country. That childish wonder still clings to me. We spent that Saturday afternoon huddled together beneath the windows, silently gazing at each other’s mournful countenance as we strained our ears to catch every sound, even though they chilled us to the heart.

As wave after wave of Union attacks failed to take the heights hundreds of wounded men streamed back into town and sought refuge in any structure they could find. Churches, public buildings, and private homes were all turned into hospitals and the streets filled with the injured and the dead.

With Burnside’s defeat and retreat back across the river, civilians began to emerge from basements and return from their temporary homes to face a town destroyed. Besides the bombed and burned out buildings, the evidence of looting was overwhelming. “Let us enter this house,” wrote Mamie Wells:

It belongs to an intelligent, enterprising citizen, who fled with his wife the morning of the eleventh. See the empty portrait frames upon the wall! Upon the floor lies a portion of the canvas, an aged face, mayhap one long since buried beneath the sod. We cannot enter this room; for a barrel of molasses has been poured upon the velvet carpet. The piano is covered with salt pork, the keys are broken and the wires cut. The mirrors are shattered; gas fixtures trampled upon; the bottoms of the sofas are cut out; chairs split with axes, and the plastering, even the laths, torn from the wall. We will go upstairs. Here are the relics of handsome dresses torn to ribbons. There is no bedding—that lies in the street in the mud. This carpet has been spread with butter. The doors of the wardrobes and washstands are broken off, and ruin stamped upon everything around. There is no silver to be found anywhere—a portion of that we have already seen in the possession of a Federal officer. The owner of this once pleasant home will return in a few days to find but the shadow of a house; not a change of garments for himself, wife or child; not an article of value left him either at his house or store.

Fanny White’s family came home to find their living room filled to the windows with feathers. The streets were filled with furniture, books, clothing, even a stuffed alligator. People’s lives, trampled in the mud. Families took stock of their losses and tried to survive and rebuild. “I can tell you much better what they left,” stated Joseph Alsop, “than what they destroyed.” Besides the physical damage, injured soldiers remained in town and the dead bodies and fresh graves lay scattered over the landscape. Fredericksburg residents now had to pick up and move on amidst the destruction around them.

The destruction of Fredericksburg shocked the South and fueled anger against the Union troops. Charitable contributions poured in from the Confederacy to help residents survive the winter and rebuild the town. Soldiers in James Longstreet’s corps raised $1,391 and in total the city received $170,000 plus gifts of supplies. Even such generosity fell short of the scale of need and Fredericksburg struggled through the remainder of the war.

December 1862 was not the first time Fredericksburg encountered the armies, and it would not be the last. Situated between the two wartime capitals, the city would play host to both armies several times during the war. The destruction of the city was so bad that some families never returned and it would take over a century for Fredericksburg to recover. Scars of the ordeal still exist today.

Suggested Reading

Blair, William A. “Barbarians at Fredericksburg’s Gate” The Impact of the Union Army on Civilians.” In The Fredericksburg Campaign: Decisions on the Rappahannock. Edited by Gary Gallagher. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1995.

Felder, Paula, and Barbara Willis, eds. The Journal of Jane Howison Beale of Fredericksburg, Virginia. Fredericksburg, 1979.

Hennessy, John. “For All Anguish, For Some Freedom: Fredericksburg in the War.” Blue and Gray (Winter 2005).

O’Reilly, Francis Augustín. The Fredericksburg Campaign: Winter War on the Rappahannock. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2006.

Rable, George. Fredericksburg! Fredericksburg! Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2002.

Kathleen Logothetis Thompson graduated from Siena College in May 2010 with a B.A. in History and a Certificate in Revolutionary Era Studies. She earned her M.A. in History from West Virginia University in May 2012. Her thesis “A Question of Life or Death: Suicide and Survival in the Union Army” examines wartime suicide among Union soldiers, its causes, and the reasons that army saw a relatively low suicide rate. She is currently pursuing her PhD at West Virginia University with research on mental trauma in the Civil War. In addition, Kathleen has been a seasonal interpreter at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park since 2010 and has worked on various other publications and projects.