Seceeding from the Secessionists: Creating West Virginia

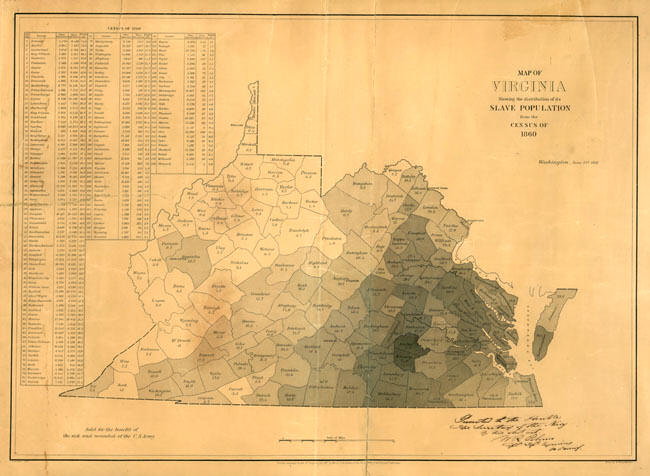

/From the very beginning, there was division between eastern and western Virginia. Families in western Virginia did not usually own the land on which they lived which excluded those white men from voting, and they generally did not own slaves. This was very different than eastern Virginia where there was a larger degree of land and slave ownership. Western Virginia was largely tied to white wage labor in a rapidly industrializing economy and many of the area’s residents supported abolition because they felt slaves were taking jobs that white laborers should be paid to do. This led to steady conflict over the years about voting rights and representation in the state government. In October 1829, prominent Virginians met to develop a new constitution and eastern conservatives defeated every reform proposed by western Virginians. The new constitution was approved statewide 26,055 to 15,566, but in western Virginia voters rejected it 8,365 to 1,383.

There was some resolution in 1850 at a Reform Convention in which eastern and western Virginians compromised on many of the issues left unresolved from 1829, and with the 1850 Constitution eastern and western Virginians seemed politically closer than ever before. National depression in 1857, however, defeated most attempts to support the industry in the western counties and tension rose again. The start of the Civil War brought those tensions to a head. On April 17, 1861, right after the firing on Fort Sumter, a convention of Virginians voted to submit a bill of secession for a vote of the people. Many western delegates marched out of the Secession Convention and vowed to create a state government loyal to the Union. These delegates met at Clarksburg, WV on April 22 and called for a pro-Union Convention which met in Wheeling from May 13 to 15. Days later, on May 23, Virginia voters approved the Ordinance of Secession and the state joined the Confederacy.

The Second Wheeling Convention, meeting in June 1861, formed the Reorganized Government of Virginia and chose Francis H. Pierpont as governor. President Lincoln recognized this body as the legitimate government of Virginia and placed pro-Union delegates in the Senate and House. The residents of 39 western counties voted to form a new Unionist state on October 24, 1861, although the accuracy of this vote has been questioned because of the presence of Union troops at the polls. In addition to these 39 counties, delegates at the Constitutional Convention selected other counties for inclusion based on political, economic, or military need bringing the total up to 50 counties. On May 29, 1862 Senator Waitman T. Willey formally petitioned for the admission of West Virginia into the Union.

The United States Constitution states that a new state must gain approval from the original state, in this case Virginia. Lincoln avoided this roadblock, and bypassed the Constitution, by his recognition of the Reorganized Government as the legitimate government of Virginia. The one hiccup to the process was demands by northern Congressmen, particularly Senator Charles Sumner, for the inclusion of an emancipation clause. The Senate rejected the first statehood bill because it did not contain that clause. After some debate, compromise was made in the form of the Willey Amendment which provided for graduate emancipation in the state. With the addition of the Willey Amendment the Senate approved statehood on July 14, 1862 and the House followed suit on December 10. Lincoln signed the bill into law on December 31, 1862, approving the creation of West Virginia as a loyal Union state and passed the issue on to the people for a vote. Citizens in the western counties voted on March 26, 1863 approving the statehood bill and West Virginia was officially born on June 20, 1863.

The creation of a new state led to more internal divisions within West Virginia. In May 1863, the Constitutional Party ran their candidate for governor, Arthur I. Boreman, unopposed. The Restored Government of Virginia and Pierpont (who continued as governor) moved into Virginia following the war and challenged the legality of West Virginia statehood. Pierpont called for elections in Berkeley and Jefferson counties to determine whether those two counties should be in Virginia or West Virginia, but the vote was swayed by the presence of Union troops at the polling sites. The two counties were awarded to West Virginia in 1871 by the US Supreme Court.

In addition, the creation of a new Union state did not automatically sway all loyalties to the north. Men from West Virginia fought for both Union and Confederate armies. Men who fought for the Confederacy often could not return home during the war for fear of capture, and in the post-war years tension between family members and neighbors over divided loyalties caused conflict that sometimes escalated into violence.

The state of West Virginia was born from division: first east-west division within Virginia, then north-south division in the lead-up to war, and then physical division into a new Union state. Within the state divided loyalties created tension between families and neighbors that marked much of the state’s early years. After the war there were calls to reunite the two divided portions of Virginia, but that never happened and West Virginia remains the only state truly born from the chaos of the Civil War.

Suggested Reading:

Michael B. Graham. Coal River Valley in the Civil War, The West Virginia Mountains, 1861. The History Press, 2014.

W. Hunter Lesser. Rebels at the Gate: Lee and McClellan on the Front Line of a Nation Divided. Sourcebooks, 2005.

John W. Shaffer. Clash of Loyalties: A Border County in the Civil War. West Virginia University Press, 2003.

Mark A. Snell. West Virginia and the Civil War: Mountaineers Are Always Free. The History Press Civil War Sesquicentennial Series, 2011.

Kathleen Logothetis Thompson graduated from Siena College in May 2010 with a B.A. in History and a Certificate in Revolutionary Era Studies. She earned her M.A. in History from West Virginia University in May 2012. Her thesis “A Question of Life or Death: Suicide and Survival in the Union Army” examines wartime suicide among Union soldiers, its causes, and the reasons that army saw a relatively low suicide rate. She is currently pursuing her PhD at West Virginia University with research on mental trauma in the Civil War. In addition, Kathleen has been a seasonal interpreter at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park since 2010 and has worked on various other publications and projects.