Sculpting the Lincoln Image: The Lincoln Memorial and Mount Rushmore in Popular Memory

/“No great character in all history has been more eulogized, no towering figure more monumented, no likeness more portrayed. Painters and sculptors portray as they see, and no two see precisely alike. So, too, is there varied emphasis in the portraiture of words; but all are agreed about the rugged greatness, the surpassing tenderness, the unfailing wisdom of this master martyr.”

These words, spoken in 1922 by a president who inspired few, eloquently captured the enduring legacy of a president who continues to galvanize change 150 years after his death. Although Lincoln was a controversial figure at his time, and remains so today, his image is undisputedly entrenched in the American consciousness. Warren G. Harding’s speech at the dedication of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. characterized not only a time of fervent memorialization in the early 20th century, but coincided with another behemoth Lincoln sculpture being constructed in the Black Hills of South Dakota. Together, the Lincoln Memorial and Mount Rushmore represent the indisputable inclusion of Abraham Lincoln on the short list of those who Americans consider to be their greatest presidents.

Today, the Lincoln Memorial and Mount Rushmore are two of America’s most famous and highly visible public spaces. An image of the Lincoln Memorial was adopted for the back of the penny in 1959. Mount Rushmore continues to attract around two million visitors per year, despite its remote location. Both landmarks have been used as backdrops for other famous speeches, campaign ads, and even Hollywood films.

However, the construction of these landmarks that have become as much a part of the American landscape as the Grand Canyon or Old Faithful were fraught with conflicting ideas, administrative setbacks, and the difficult task of determining whose Lincoln image would be portrayed.

To Americans both in the 1920s and now, Lincoln is less of a person than a myth, a martyr, and a legend. Despite scholarship highlighting negative aspects of Lincoln’s presidency, those critical of his use of executive power, and less critical attempts to humanize our sixteenth president, images of Lincoln as the Savior of Democracy, the Great Emancipator, the Rail-splitting Statesman persist. Abraham Lincoln has become larger than life, and it is fitting that the two most famous representations of Lincoln on the American memorial landscape are massive sculptures.

Work began on the Lincoln Memorial nearly 50 years after Lincoln’s death, and characterized the both the reconciliationist attitudes and patriotic memorialization at the time. Vague thoughts of a possible Lincoln memorial existed even when Lincoln was still on his deathbed, although at this time no national memorial had been built to any president except George Washington. The area where the Lincoln Memorial now stands, an integral part of the famous Washington Mall, did not exist until the late 19th century. After the Army Corps of Engineers deepened the Potomac River, dredged silt created a portion of muddy land, which would not be fit for construction until the early 20th century. Construction on the memorial officially began in 1914.

The Lincoln Memorial has often and accurately been described as a temple. Designed by architect Henry Bacon, the memorial was modeled after the Greek Parthenon and thus steeped in illusions to the birthplace of democracy. Thirty-six exterior columns are stand-ins for the thirty-six states that had reunited by the time of Lincoln’s death in 1865. Inside the three-chambered memorial, Lincoln’s statue is flanked by two of his most famous and impactful speeches, the Gettysburg Address and his Second Inaugural.

Above each of the speeches are two murals painted by artist Jules Guerin, both depicting the figure of the “Angel of Truth.” Above the Gettysburg Address is the angel surrounded by recently freed slaves, focusing on Emancipation. Conversely, the angel above the Second Inaugural Address is surrounded by representatives from the North and South, therefore depicting reunification.

Then there is the iconic statue itself. The work of sculptor Daniel Chester French, who, after meticulous study of Lincoln’s photographs and character, chose to depict two prominent qualities: his strength and compassion. One of Lincoln’s hands is clenched in a fist, said by the artist to represent both his strength and determination to reunify the nation. The other hand is relaxed, open, and more welcoming.

Work on the memorial was steady until April of 1917, when the United States’ entry into World War I slowed progress. However, the recent war would characterize the dedication ceremony in 1922, as well as what Americans in the 1920s would choose as their Lincoln image.

The memorial was dedicated on May 30, 1922 with around 50,000 people in attendance. Occurring on the footsteps of a war in which Americans from the North and South had fought and died together, the message of this ceremony largely focused on Lincoln as a “Great Unifier.” Harding’s speech highlighted this:

“How it would comfort his great soul to know that the States in the Southland join sincerely in honoring him, and have twice, since his day, joined, with all the fervor of his own great heart, in defending the flag!”

This pattern fits into the reconciliationist undertone of much of the Civil War commemoration at this time. However, this focus on reunification meant that Lincoln’s involvement with Emancipation was relegated to a secondary role or ignored entirely, which silenced the voice of the United States’ African American population. The United States had a segregated standing army at this time, and with the exception of Union Civil War veterans present at the dedication, the ceremony was segregated as well. Although the United States was once again one nation, unity on every front had not yet been achieved.

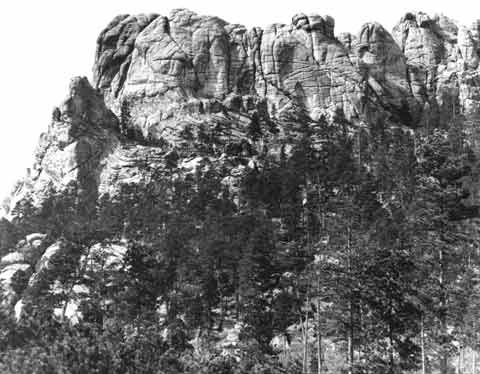

At around the same time, in the Black Hills of South Dakota, another memorial was about to begin construction.

Mount Rushmore placed Lincoln’s likeness with those of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Theodore Roosevelt as one of the four presidents early twentieth century Americans considered to be the most influential on the development of their nation. Furthermore, a dedication speech by Calvin Coolidge in 1927 claimed that Lincoln was not only one of the most remembered, but the most loved:

“After our country had been established, enlarged from sea to sea, and was dedicated to popular government, the next great task was to demonstrate the permanency of our Union and to extend the principle of freedom to all inhabitants of our land. The master of this supreme accomplishment was Abraham Lincoln. Above all other national figures, he holds the love of his fellow countrymen. The work which Washington and Jefferson began, he extended to its logical conclusion.”

Few contemporary Americans could imagine Mount Rushmore without the faces of four of our most famous leaders. However, this monument in stone nearly did not happen for several reasons.

Initial ideas for the monument included figures of frontier heroes of the American West, such as Lewis and Clark and Buffalo Bill Cody. However, Gutzon Borglum, the sculptor chosen for the project, wanted the mountain to have a more national focus. Stating, "The purpose of the memorial is to communicate the founding, expansion, preservation, and unification of the United States with colossal statues of Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln, and Theodore Roosevelt," Borglum illustrated the highly nationalistic sentiments of the early 20th century.

Borglum himself was nearly not available for the project. Ironically, he was initially selected to sculpt Stone Mountain, a representation of three Confederate figures, Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, Robert E. Lee, and Jefferson Davis, in Georgia. He left the project due to creative disputes in 1925, only completing Lee’s head, which was removed by later sculptors. However, Borglum’s general design plan to have the three figures on horseback endured, and he learned many of the techniques later used on Mount Rushmore during his foray into Lost Cause memorialization.

Issues with funding continuously plagued the project. Initially, a combination of federal funding and private donations funded the project. With the signing of Executive Order 6166 in 1933, Mount Rushmore now fell under the jurisdiction of the National Park Service, which caused tension between Borglum and government officials over creative and administrative control. The sculptor spent much of the last two years of his life travelling in search of continued funding.

The amount of manpower involved in the building of Mount Rushmore was monumental in itself. Over 400 men and women participated in the project. The Great Depression facilitated a steady stream of willing workers, who faced extreme weather conditions such as intense summer heat to high winter winds. A job carving the mountain meant facing not only the 500 foot face of the landform but also the dynamite used to create the undetailed shapes of the faces. Miraculously the project suffered not a single fatality.

Few of the workers understood the long-term impact of their project. Famously, several workers were interviews and asked the simple question, “What is it you do here?” One answered, “I run a jackhammer.” Another responded, “I earn $8.00 a day,” illustrating the importance of a steady wage in Depression-era America. A third worker answered differently, stating “I am helping to create a memorial.” That worker may have had an idea of the significance of this project, but it is doubtful that he knew just how many future Americans would gaze upon those four stone faces.

Sadly, Gutzon Borglum died in March of 1941, just months before Mount Rushmore National Monument was declared a completed project on October 31st of the same year. Creative control was relinquished to Borglum’s son, appropriately named Lincoln after his father’s favorite president.

The powerful hold Lincoln has on Americans has caused even other presidents to invoke language of reverence and awe. Harding’s 1922 speech once again illustrates how even the most powerful American at the time saw Lincoln not as a peer, but as an idol:

“Somehow my emotions incline me to speak simply as a reverent and grateful American rather than one in official responsibility. I am thus inclined because the true measure of Lincoln is in his place today in the heart of American citizenship, tough more than half a century has passed since his colossal service and his martyrdom. In every moment of peril, in every hour of discouragement, whenever the clouds gather, there is the image of Lincoln to rivet our hopes and to renew our faith. Whenever there is a glow of triumph over national achievement, there comes the reminder that but for Lincoln’s heroic and unalterable faith in the Union, these triumphs could not have been.”

Decades after the dedication of these two monuments, the meaning of both, and of Lincoln himself, to contemporary Americans has changed. However, the prominence of these two representations has only grown. The Lincoln Memorial is now famous as the setting for one of the most famous events in the Civil Rights movement, Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech. Mount Rushmore had become perhaps the most popular image used to depict great American presidents, and visitation to the site continues to increase.

The rededication of the Lincoln Memorial in 2009, on the bicentennial of his birth and the four score and seven-year anniversary of the May 30, 1922 dedication ceremony, shows that although specific meanings of monuments change, the fact that monuments are endowed with meaning persists. Lincoln was important to Americans in 1865, in 1922, and today. Four score and seven years from now, the image of Abraham Lincoln will most likely mean something entirely different to a new generation of Americans, but he will almost certainly mean something.

Although it is important to uncover “Lincoln the Man,” to not disregard his faults, and to accept that he did indeed make mistakes, how we continue to mythologize “Lincoln the Legend,” tells us that Lincoln’s true enduring image is the ability for his image to endure. That Lincoln can continue to inspire Americans today is illustrated by the National Park Service’s statement that “The Lincoln Memorial remains here, with timeless patience, reminding us every day that we must always strive toward a united, equal, and free society. We only need to listen.”

Becky Oakes, a graduate of Gettysburg College, is currently finishing her master’s degree in 19th-century U.S. History and Public History at West Virginia University. Becky’s research focuses on Civil War memory and cultural heritage tourism, specifically the development of built commemorative environments. She also studies National Park Service history, and has worked at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park, Gettysburg National Military Park, and the Civil War Institute at Gettysburg College.©

Sources and Further Reading:

Hogan, Jackie. Lincoln, Inc.: Selling the Sixteenth President in Contemporary America. New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2011.

Jividen, Jason R. Claiming Lincoln: Progressivism, Equality, and the Battle for Lincoln’s Legacy in Presidential Rhetoric. DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 2011.

Schwartz, Barry. Abraham Lincoln and the Forge of National Memory. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2000.

Thomas, Christopher A. The Lincoln Memorial & American Life. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2002.