Looking for the American Dream: Lincoln Statues in the Great Depression

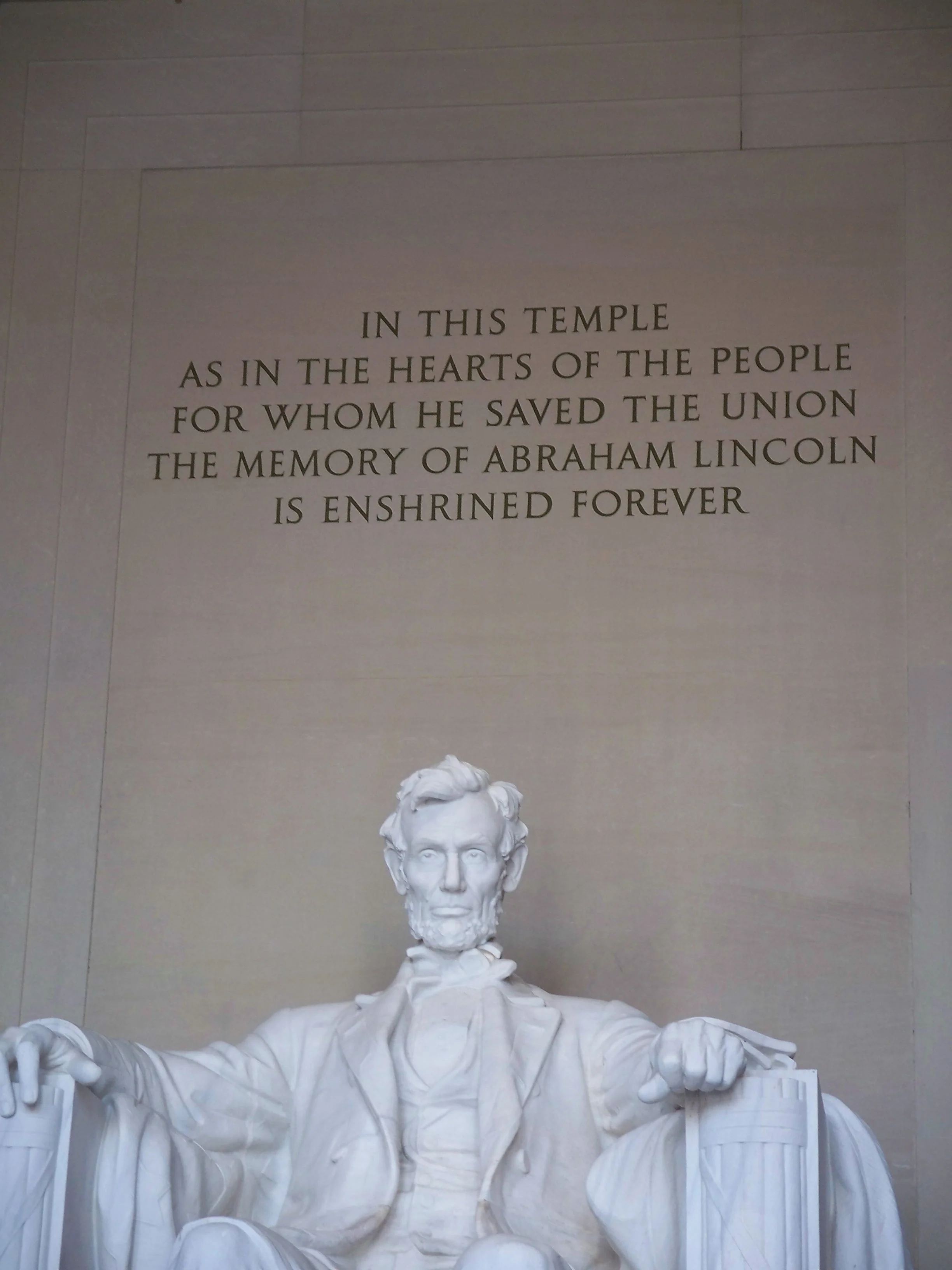

/Lincoln Memorial, Washington, DC

America is a nation dotted with monuments to its achievements and national heroes. In this theme few individuals have been honored with as many monuments and memorials as Abraham Lincoln. From local and state initiatives to the grand Lincoln Memorial that graces the National Mall, and has become a prime attraction in the United States Capital, Abraham Lincoln is heralded as one of our greatest presidents and a national icon. Interestingly, Abraham Lincoln is also one of the only American figures whose youth is widely commemorated. Even George Washington, the “Father of our Country,” has no statues dedicated to celebrating him as a child. Lincoln is unique in the fact that his childhood remains a critical part of what made him a great national hero. There are under a dozen statues to Lincoln as a youth and they were all completed in the early twentieth-century. Six out of the nine statues were completed in the period between 1930 and 1944, the time of America’s Great Depression; two of these statues are featured here. During the Depression, Abraham Lincoln meant more to the country than a great president, he was a symbol of hope and the American Dream, and in this period Lincoln statuary reflected the attitudes and needs of the American people.

The Great Depression, known for its high unemployment rates and personal hardships, created a dilemma for the United States Government. Something needed to be done to help the increasing numbers of people out of work and out of their homes, but the nation held a firm view of work and charity. To the majority of the country the ideals that white, Protestant culture held up as Americanism remained central. Self-reliance, individual initiative, hard work, honesty, and independence had built America and anything that would weaken that tradition would weaken America itself. Government charity was the embodiment of evil because it robbed people of the initiative that was so important to America’s character. Most people believed that the government should stay out of people’s personal lives and the idea that individuals would turn to the government for help was unthinkable. America believed in the “gospel of work,” the self-made man, and the “myth of America success” where opportunity existed and the only essential quality was a willingness to work.

In addition to attitudes towards work, the public atmosphere in the 1930s was conducive to increased commemoration of Abraham Lincoln. There was a revival of interest in the fate and past of ordinary people due to the dialogue of those who were struggling with unemployment and hard times, the protests of workers, and the actions of a government trying to reassure and address the concerns of the citizens. Economic decline and social unrest brought into question fundamental values promoted in the twentieth-century. The future looked uncertain so Americans looked to the past for proof that they had overcome hard times before. This interest manifested itself in commemorative activities which fused the image of the pioneer with patriotism. To Americans, especially in the Midwest, the pioneers had always represented the ordinary people who had faced and overcome difficult times. In 1938, when the sesquicentennial of the first settlement in the Northwest Territory at Marietta, Ohio was commemorated, it was decided to celebrate the strength and heritage of the pioneers, as well as the unity of a diverse community, by staging a “pioneer caravan” retracing the route from Massachusetts to Marietta. The idea of the pioneer and the frontier called up nostalgia of a lost past. This was strengthened by the ideas expressed by Frederick Jackson Turner in his paper “The Significance of the Frontier in American History” which was first read in the 1890s. The frontier, he said, was the explanation to how America developed into the grand nation is was:

Frederick Jackson Turner

Up to our own day American history has been in a large degree the history of the colonization of the Great West. The existence of an area of free land, its continuous recession, and the advance of American settlement westward, explain American development…The peculiarity of American institutions is, the fact that they have been compelled to adapt themselves to the changes of an expanding people—to the changes involved in crossing a continent, in winning a wilderness, and in developing at each area of this progress out of the primitive economic and political conditions of the frontier into the complexity of city life.

America was unique because there had been no limits to its expansion. Now, however, the frontier was closed and the first period of American history had ended. The pioneer symbol was widely used because it was diverse enough to cover the needs of a wide variety of people and it was the example of the American ideology of self-improvement. In the period after the First World War, however, the patriot symbol was mixed with that of the pioneer because the concept of self-improvement was not enough; Americans also needed to celebrate self-sacrificing citizens who placed the common good over their individual interests.

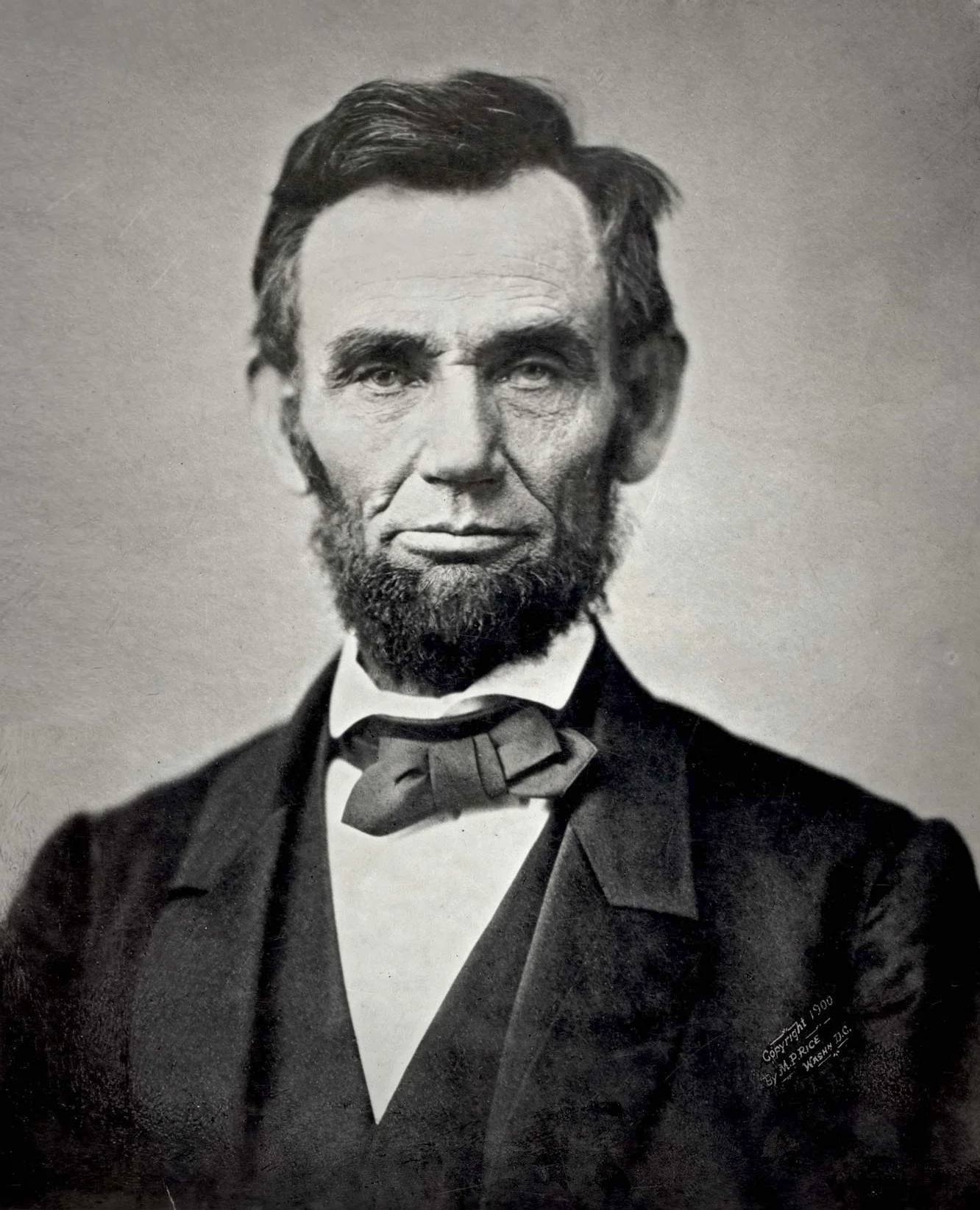

Lincoln's legacy grew in the 1930s

On February 1, 1931, President Herbert Hoover addressed the nation by radio, “Victory over this depression and over our other difficulties will be won by the resolution of our people to fight their own battles in their own communities, by stimulating their ingenuity to solve their own problems by taking new courage, to be masters of their own destiny in the struggle of life. This is not the easy way but it is the American way. And it was Lincoln’s way.” Hoover connected Abraham Lincoln directly to the fundamental “American way” and he urged Americans to show the same commitment, courage, and resourcefulness as in Lincoln’s day. Lincoln had begun his transformation into a national icon in the late Nineteenth-Century. He was the man who had upheld liberty and freed the slaves and he could rival George Washington in sacrifice, service to the nation, and exceed him in martyrdom. In addition, in the atmosphere of the pioneer symbol, he was a humble and ordinary man who had retained some of his pioneer ideas and mannerisms as he rose in power. In the Progressive Era (1900-1920), Lincoln rose even more in national esteem. He was a “fusion of potential and achievement” in a time when the businessman reigned supreme. It was during the 1920s that Lincoln surpassed George Washington in the public’s opinion of presidential greatness, a position he has held since. Lincoln’s historical renown, however, would reach its apex in the 1930s.

The people of the 1930s believed in greatness and were waiting for another Lincoln or Washington to emerge in their time, but they also connected with folk heroes who represented the masses and were a touchable and imperfect representation of society. American folk lore humanized Lincoln and made him a man that ordinary people could identify with, the “compassionate Man of the People.” His childhood as part of a frontier family connected with the nostalgia for a lost past that was growing in the early twentieth-century. Images of a young Lincoln splitting logs and the log cabin myth exaggerated the poverty of Lincoln’s background and reflected the view that the frontier equalized access to material growth. Lincoln was a man trying to improve himself which appealed to the people of the Depression who saw in him the mind and virtues of a self-starting businessman. Lincoln’s life was a story of commonness becoming self-made greatness. Depression images of Lincoln represented economic stability, self-reliance, interpersonal ties, and a family unity that Americans felt that they had lost. He symbolized overcoming problems and obstacles and he was often represented with the ax and the book as symbols of the virtues of hard work and labor. To America, Abraham Lincoln was the epitome of the extraordinariness of the ordinary American and, while different groups used his image to support their agendas, they all agreed that he symbolized the contribution of the common man to the nation. Liberals emphasized Lincoln’s courage, compassion, and commonness and used him as an image of someone who was not afraid to try new things when old methods failed. Conservatives stressed his ambition, hard work, persistence, and self-reliance to support government hesitance to give charitable handouts. In their view, no man can have freedom unless he has the will to work his way out of want. In his Lincoln Day address in 1940 in Buffalo, New York, Bruce Barton began by mimicking the language Roosevelt had used to describe the nation’s poor, “We are met here to honor the memory of an American who was ill-fed, ill-clothed, ill-housed—and did not know it.” Barton continued on to say that instead of quitting or calling on the government for help, Lincoln had worked hard, transformed those deprivations into pillars of strength, and conquered his birth and upbringing. Lincoln’s struggle was connected to the Depression and America could take strength from it. Despite emphasizing different aspects of Lincoln, both sides agreed that Lincoln could serve as a powerful image to the people of the Depression Era.

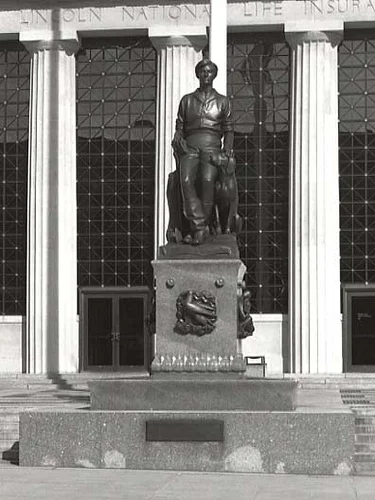

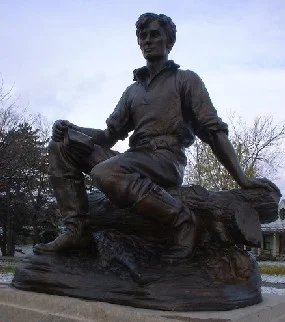

"Abraham Lincoln--The Hoosier Youth" by Paul Manship (photo credit: unknown)

The symbol of Lincoln as a common man who pulled himself out of a poor background through hard work was a powerful influence upon Depression-Era Americans, and the 1930s and early 1940s saw a wave of commemoration of Lincoln’s youth. The first of these Depression-Era Lincoln statues was unveiled in 1932 in Fort Wayne, Indiana. Sculpted by Paul Manship and commissioned by the Lincoln National Life Insurance Company to grace the front of their building, “Abraham Lincoln—The Hoosier Youth” shows a twenty-one year old Lincoln clad in the rough clothing of a frontiersman, resting on an oak stump with his axe by his side. He holds a book in his right hand where he has marked his page with his finger as he looks out at the observer and his left hand rests on the head of a dog which tradition has it he saved from abandonment as his family was crossing an icy stream while moving to Illinois. The four faces of the square pedestal each have a bronze medallion representing the virtues of Lincoln—charity, fortitude, justice, and patriotism. The dedication on September 16, 1932 consisted of a luncheon with a series of short addresses, the unveiling, and a program for schoolchildren in the plaza in front of the monument. The first speaker of the day was Dr. Joseph R. Sizoo whose address chronicled Lincoln’s youth and how he rose to greatness with humbleness. In his Dedicatory Address, the Honorable Arthur M. Hyde captured the 1930s sentiment towards Lincoln:

The Life of Abraham Lincoln is the epic of Americanism. From it, mothers gather hope for the future of their children. In it, the youth of our land see equality of opportunity. Because of it, there is no boy or girl in all America so poor or so wretched in birth or in surroundings but may dream of the loftiest attainment. The life and achievements of Abraham Lincoln is the guaranty of their opportunity…No life in history more ennobles the common man…He was the physical embodiment of that spirit of equality, of that love of ordered liberty, and of that self-discipline which are the fundamental tenets of Americanism…his life stands forth as the apotheosis of the common man, the great epic of American equality and opportunity.

Ida Tarbell continued this theme in her speech when she said, “Here you have a son of the Republic, one who early dreamed its dream.”

"The Boy Lincoln" by Percy Bryant Baker (photo credit: unknown)

Three years later Percy Bryant Baker’s “The Boy Lincoln” was unveiled in Delaware Park in Buffalo, NY. The bronze statue is situated on a low pedestal near the entrance to the park and has Lincoln seated on an oak with an axe at his feet and a book on his knee. Baker expressed that he was interested in the rise of Lincoln from frontiersman to president and his struggle against tremendous odds. He felt that Lincoln must have had an awakening to the personal responsibility to educate himself and he “wanted to express the vision that had come to him, the vision that later proved him to be above all else a great philosopher, statesman and humanitarian.” At the October 19, 1935 dedication Richard H. Templeton, a former United States attorney, used as the theme for his address the words that Lincoln supposedly said as a boy: “I will study and be ready. Then maybe the chance will come.”

Four other Lincoln youth statues were done during the Great Depression and two were done as the nation dealt with WWII. After this period the focus returns to Lincoln as President and Emancipator. The 1930s in America created an atmosphere that promoted the common, self-made image of Lincoln. The abhorrence of charity and handouts and the emphasis on finding jobs and providing work relief brought focus to Lincoln’s days as a frontiersman, living by the axe and his own strength and sweat. The conditions that people found themselves in made Americans look to Lincoln as an example of someone who had pulled themselves out of poverty to make it all the way to the highest position in the country. Lincoln gave America hope that they would survive the Great Depression as America had survived the Civil War. And Lincoln fueled the American Dream, the idea that anyone, no matter what their station in life, could work their way to success. The “Man of the People” Lincoln fit the Great Depression needs of America, and artistic sculpture reflected those needs and desires.

Bibliography and Further Reading:

Addresses delivered at the Dedication of the heroic bronze statue “Abraham Lincoln---The Hoosier Youth”, September 16, 1932, Entrance plaza of The Lincoln National Life Insurance Company, Fort Wayne, Indiana.

Bodnar, John. Remaking America: Public Memory, Commemoration, and Patriotism in the Twentieth Century. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1992.

Bullard, F. Lauriston. Lincoln in Marble and Bronze. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press [1952].

Durman, Donald Charles. He Belongs To The Ages: The Statues of Abraham Lincoln. Ann Arbor, MI: Edwards Brothers, Inc., 1951.

Fairbanks, Eugene F. Abraham Lincoln Sculpture created by Avard T. Fairbanks. Eugene F. Fairbanks, 2002.

Hern, Charles R. The American Dream in the Great Depression. Westport, Ct: Greenwood Press, 1977.

Kennedy, David M. Freedom From Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929-1945. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Peterson, Merril D. Lincoln in American Memory. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.

Pitcaithley, Dwight T. “Abraham Lincoln’s Birthplace Cabin: The Making of an American Icon.” In Myth, Memory, and the Making of the American Landscape, edited by Paul A. Shackel, 240-254. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2001.

Rose, Nancy E. Put to Work: Relief Programs in the Great Depression. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1994.

Schwartz, Barry. Abraham Lincoln and the Forge of National Memory. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2000.

---. Abraham Lincoln in the Post-Heroic Era: History and Memory in Late Twentieth-Century America. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2008.

Turner, Frederick Jackson. The Frontier in American History. Malabar, FL: Robert E. Krieger Publishing Company, 1985.

Watkins, T. H. The Great Depression: America in the 1930s. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1993.

Kathleen Logothetis Thompson graduated from Siena College in May 2010 with a B.A. in History and a Certificate in Revolutionary Era Studies. She earned her M.A. in History from West Virginia University in May 2012. Her thesis “A Question of Life or Death: Suicide and Survival in the Union Army” examines wartime suicide among Union soldiers, its causes, and the reasons that army saw a relatively low suicide rate. She is currently pursuing her PhD at West Virginia University with research on mental trauma in the Civil War. In addition, Kathleen has been a seasonal interpreter at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park since 2010 and has worked on various other publications and projects.