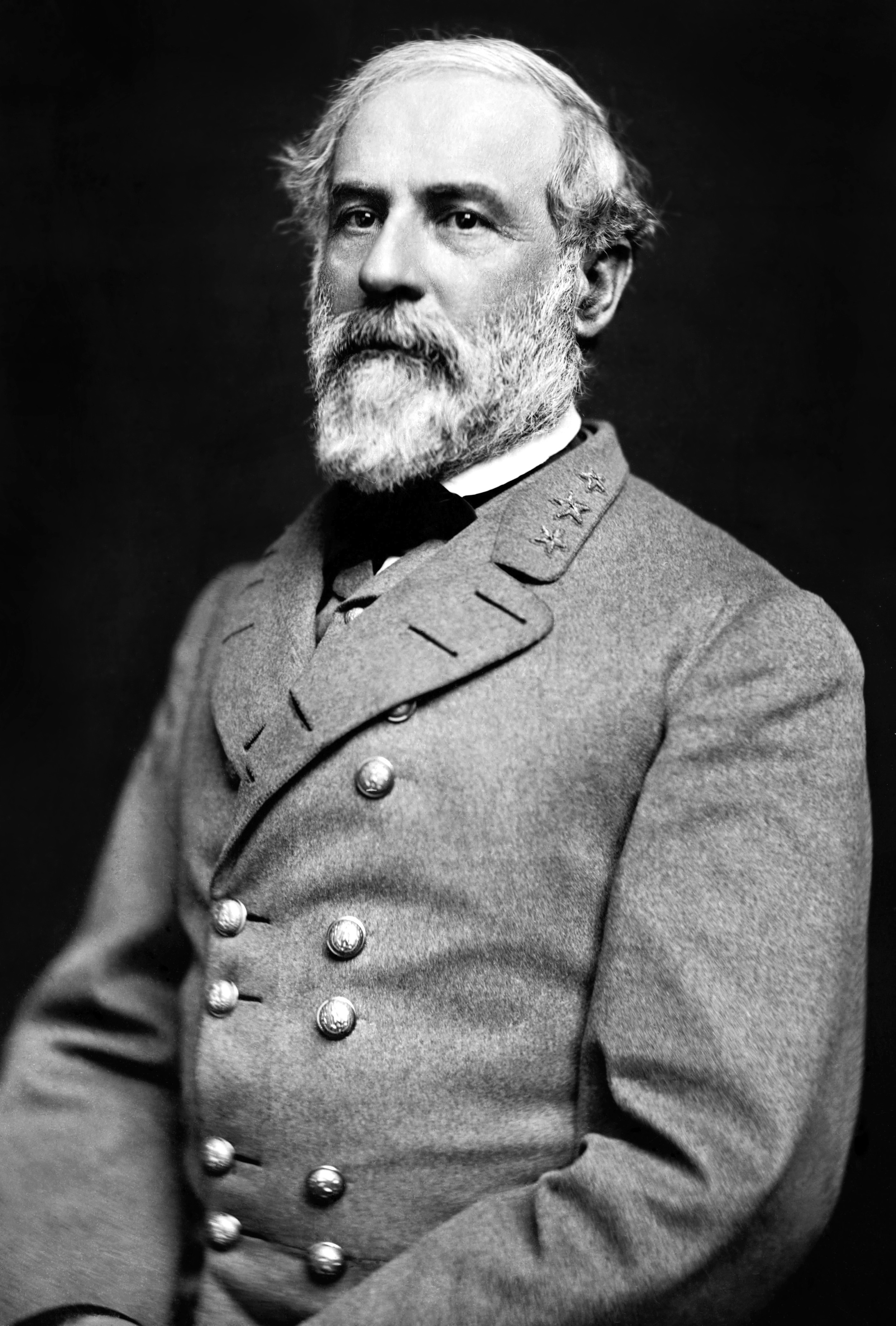

Did Robert E. Lee Kill A Man? Did Douglas Southall Freeman Cover It Up?

/Tucked away in a brief footnote within later editions of Douglas Southall Freeman's monumental four volume R.E. Lee, the famous Civil War historian penned a short account of an intriguing and "unhappy" episode in Robert E. Lee's younger life. The young Lee spent the summer of 1835 surveying the boundary between Ohio and Michigan Territory. Buried in a Freeman footnote, we learn the following:

An unhappy incident of Lee's experience on this survey was the accidental death of a Canadian lighthouse keeper "in a scuffle" over the use of his tower for running one of the survey lines. The only reference to this, so far as is known, is in Lee to G.W. Cullum, July 31, 1835...A search of Canadian records yields no details.

Freeman's account is rather vague. The Robert E. Lee letter Freeman references is more explicit. Lee wrote to his friend that, after breaking into the lighthouse on Pelee Island:

...we discovered the keeper at the door. We were warm & excited, he irascible & full of venom. An altercation ensued which resulted in his death....I hope it will not be considered that we have lopped from the Government a useful member, but on the contrary--to have done it some service, as the situation may now be more efficiently filled & we would advise the New Minister to make choice of a better Subject than a d----d Canadian Snake.

Did Robert E. Lee kill a man? And did Douglas Southall Freeman bury the horrifying incident in a footnote?

The simple answer is that Lee--the "Marble Man" himself--did not kill a man. In fact, his letter was quite specific on what he did kill...a snake! Writing a facetious letter to his friend, Lee in mock seriousness penned an account of killing a "d----d Canadian" serpent, "irasible [sic] and full of venom." Historians have combed through the series of letters Lee wrote during this period, and it is clear that Lee often joked with his close friend George Washington Cullum in their correspondence. The affair with the lighthouse "keeper" was just the same, a jesting letter between friends.

To quell your perhaps still-doubtful hearts, research by historian John Gignilliat essentially confirms that no murder took place. In 1835, there was no permanent lighthouse keeper on Pelee Island, and only one man lived on the island (William McCormick...who died in 1840). No lighthouse keeper, human anyways, existed for Lee and his party to kill. Beyond this, no persons went missing that summer, nor did the local McCormick family (who still lived on Pelee as of 1971) have any knowledge or rumor of a murdered man.

Lee, then, can be absolved for his crime of killing a snake.

Perhaps a little less worthy of absolution is Douglas Southall Freeman, who apparently misinterpreted the letter, took it too seriously, and thought that Robert E. Lee did in fact kill a man. Freeman acquired the Lee-Cullum letter shortly after the publication of his Pulitzer-winning R.E. Lee in 1935, which portrayed Lee as a paragon of virtue and morality. Recognizing the affair as "sensational", Freeman consistently promised those who knew of the letter's contents that he would put the account in the next edition of his work. "I think, in justice to historical truth," Freeman affirmed, "I should, in the next printing, publish the letter, because there probably will be no official 'second edition.'"

Despite these begrudging promises, it was not until February of 1949 that Freeman finally added not a full publication or even explanation of the letter, but instead a small footnote vaguely describing the whole affair. R.E. Lee was originally published in 1935, and Freeman acquired the letter (whose authenticity he did not doubt) soon after. Freeman, then, took over a decade to finally mention the affair in his volumes, even then barely shedding any real light on the incident. Considering the in-depth biographical nature of R.E. Lee, a murder committed by its main protagonist would seem to warrant far more than a vague footnote.

Perhaps it is best that Douglas Freeman did not significantly rework his masterpiece around a killing that historians and evidence today agree did not take place. Yet it remains that Freeman did not know that Lee didn't kill a man, and it is clear that he buried that supposed crime in his work, relegating the murder to a foggy footnote.

On one hand, I understand Freeman's dilemma. What do you do after publishing a Pulitzer Prize winning book extolling the virtues a Confederate icon, only to discover evidence that points to the contrary? It is a tough situation to be in, and Freeman seems to have struggled with it. On the other hand, however, Freeman's course of action should be a warning both to us historians and to you the reader. Too easily we can come to sympathize with and even care for our subjects in ways that endanger scholarship. Freeman built a "marble man" in his head, and he couldn't bring himself to tarnish that marble despite evidence to the contrary.

Robert E. Lee did not kill a man. But the thought that he might have made Douglas Southall Freeman abandon, at least for a moment, academic integrity and obfuscate what he believed to be true. It's a tale worth remembering, and a tough lesson in honesty worth walking away with. We should always be true to history...the good, the bad, and the ugly.

Sources & Further Reading:

Freeman, Douglas Southall. R.E. Lee. Vol. 1.

Gignilliat, John. "A Historian's Dilemma: A Posthumous Footnote for Freeman's R.E. Lee." Journal of Southern History, Vol. 43, No. 2 (May, 1977).

Heleniak, Roman J. & Lawrence J. Hewitt, eds. The Confederate High Command & Related Topics.