Sesquicentennial Spotlight: The 13th Amendment Passes the House

/The United States did not enter the Civil War with the intent to destroy slavery. However, by the end of the war in 1865 slavery had been dealt its death blow. Today marks the 150th anniversary of the 13th Amendment passing Congress, and moving on to the states for ratification. While the Emancipation Proclamation is more famous, it was the 13th Amendment that gave emancipation meaning and solidified the end of the war as the end of slavery in America.

Lincoln entered his presidency as the Union was falling apart. Southern states seceded in response to his election, fearing that a Northern Republican would attack slavery. Despite having a free labor, anti-slavery platform, Lincoln assured the South he was not determined to end slavery in the established southern states already committed to the institution. To back-up his words to the South, Union forces at the beginning of the war were required to return runaway slaves to their masters.

Butler with the Contraband (Library of Congress

Change started early in the war with former proslavery democrat Benjamin Butler. Assigned to command Fort Monroe in Virginia, he was forced to decide the face of three escaped slaves who arrived at the fort on May 23, 1861. When their owner, a Confederate colonel, came under flag of truce to claim his property, Butler informed the man that since Virginia had seceded the Fugitive Slave Law no longer applied. He declared the escaped slaves contraband of war because they had worked for the Confederate army, a term that was quickly applied to all slaves escaping to the Union lines. Lincoln and his cabinet approved Butler’s actions on May 30. This was solidified in the Confiscation Act which authorized the seizure of all property used in aiding the Confederacy.

As the war hardened so did the policies towards slavery. On July 17, 1862 Congress passed the Second Confiscation Act which stated that all Confederates within Union occupied territory who did not surrender within 60 days would have their slaves freed. In addition, all slaves that took refuge with the Union army would be set free as “captives of war.” Union generals, such as General John Pope, used the Confiscation Acts to form their policies on the ground.

Around the same time, that summer Lincoln decided to put plans in motion for emancipation, a stance very different from where he began at the start of the war. In an August 1862 letter to Horace Greeley Lincoln foreshadowed his changing policies on slavery:

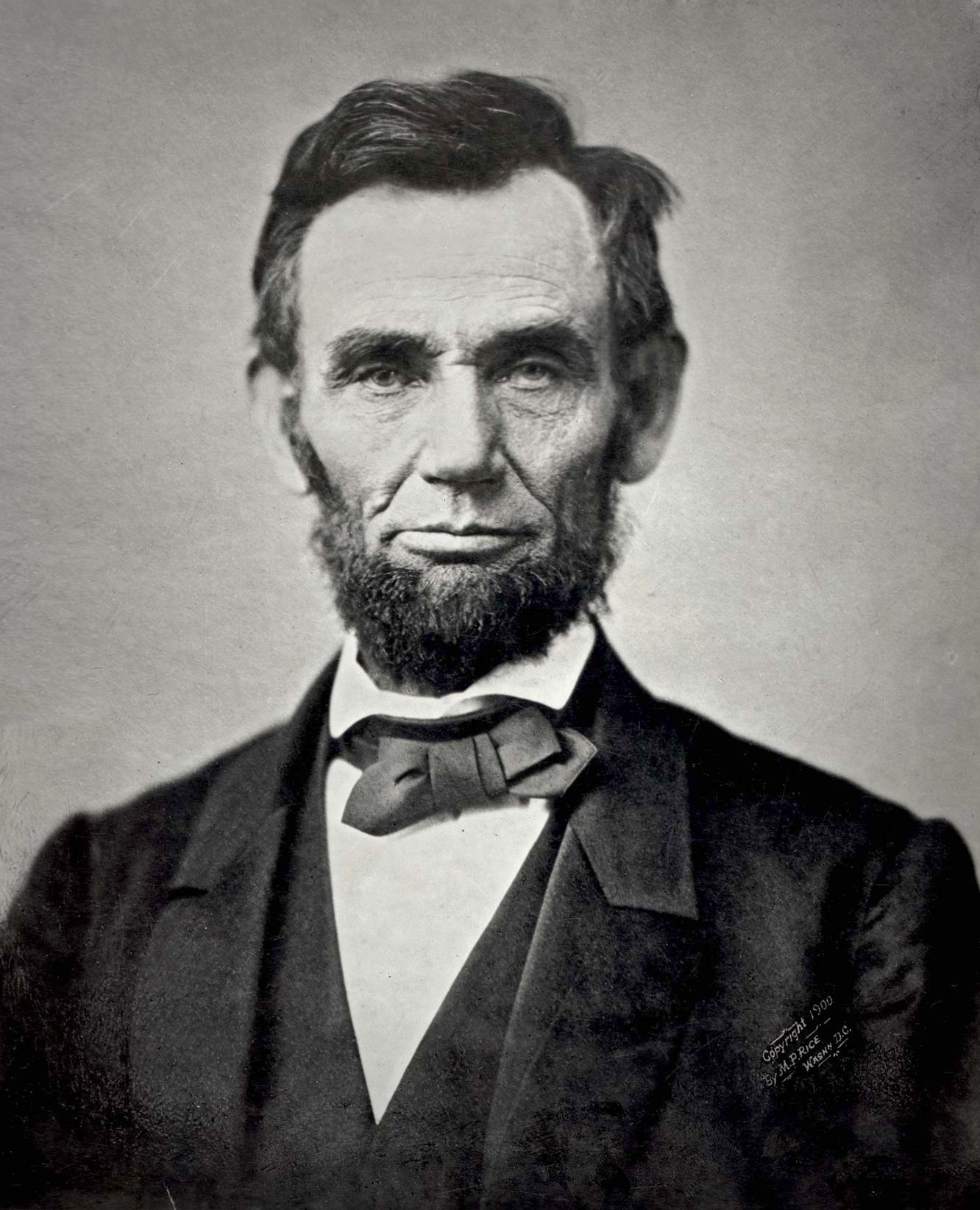

Abraham Lincoln

My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that. What I do about slavery, and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save the Union; and what I forbear, I forbear because I do not believe it would help to save the Union. I shall do less whenever I shall believe what I am doing hurts the cause, and I shall do more whenever I shall believe doing more will help the cause.

Pressure on the issue was increasing; public opinion, the confiscation policies, and the need to put pressure on the Confederacy in any way possible changed Lincoln’s mind and the course of the war. He broached the subject to Secretaries Seward and Welles in a carriage on their way to a funeral for Secretary Stanton’s son. Nine days later Lincoln called his full cabinet together to announce his decision to issue an emancipation proclamation. His cabinet members expressed a mixture of support and doubt and upon their advice Lincoln put the proclamation away until his armies could give him a military victory in the wake of which he could issue his radical policy.

Unfortunately for Lincoln, his armies suffered disappointment and defeat consistently in 1861 and 1862 in the eastern theater. Finally in September 1862 General George McClellan gave him a glimmer of hope. The Battle of Antietam was not the decisive victory Lincoln wanted, but the Union held the field at the end of the battle and General Robert E. Lee and his Confederates retreated back to Virginia. It was enough for Lincoln to pull out the dormant idea of emancipation:

I think the time has come now. I wish it were a better time. I wish we were in better condition. The action of the army against the rebels has not been quite what I should have best liked. But they have been driven out of Maryland, and Pennsylvania is no longer in danger of invasion.

On September 22, 1862, five days after Antietam, Lincoln called his cabinet together and issued the Preliminary Proclamation announcing to the Confederacy that unless they ended their rebellion he would issue the full Proclamation at the start of the new year. At that point their slaves would be freed.

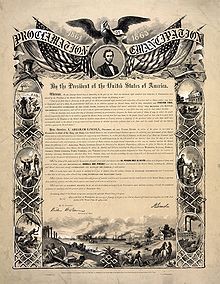

Not having the decisive victory he wanted for the Preliminary Proclamation, he pushed his new commander of the Army of the Potomac, Ambrose Burnside, to achieve victory before the end of the year. That pressure led to the disastrous Battle of Fredericksburg in December of 1862. Even with that loss looming large, Lincoln moved ahead with his plans to sign the Proclamation into law, thus redefining the Union cause and the meaning of the war. The Emancipation Proclamation changed the course of the war, from protecting the Union to redefining freedom. But far from being the bringer of widespread freedom to all enslaved peoples, the Proclamation was very limited in its power.

The declaration promised that “…all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free…” This meant that only slaves in areas not occupied by the Union would be free and slaves in Union territory would remain enslaved. This provision was to ensure that the pro-slavery Border States would not leave the Union to maintain their property in slaves. It meant that in areas where the United States had power to end slavery they could not and in areas outside Union control slaves were declared free. At the end of the Proclamation, Lincoln outlined exactly which areas were in rebellion:

Arkansas, Texas, Louisiana, (except the Parishes of St. Bernard, Plaquemines, Jefferson, St. John, St. Charles, St. James Ascension, Assumption, Terrebonne, Lafourche, St. Mary, St. Martin, and Orleans, including the City of New Orleans) Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia, (except the forty-eight counties designated as West Virginia, and also the counties of Berkley, Accomac, Northampton, Elizabeth City, York, Princess Ann, and Norfolk, including the cities of Norfolk and Portsmouth[)], and which excepted parts, are for the present, left precisely as if this proclamation were not issued.

The exempted counties in Louisiana and Virginia were areas firmly under Union control, and thus outside the influence of the Proclamation.

In the moment, the Emancipation Proclamation freed very few slaves; it was the meaning and precedent that was important. News of the Proclamation spread into the South, giving slaves hope that the end of slavery was possible. It also gave them encouragement to take actions for their own freedom, for example enlisting in USCT regiments later in the war. Lincoln knew, however, that the real power behind emancipation would have to come through a Constitutional amendment.

Although the words “slavery” and “slave” do not appear in the document, the Constitution protected the institution through passages such as the Three-Fifths Compromise and the Fugitive Slave Clause. Protection of property was very important to the founding fathers and those who came after them. In order to ensure emancipation, especially after the war, Lincoln and Northern Republicans moved toward a Constitutional amendment meant to put power behind the Emancipation Proclamation. James Mitchell Ashley, James F. Wilson, John B. Henderson, Charles Sumner, Thaddeus Stevens, and others presented initial drafts of the amendment in late 1863 and early 1864, and Lyman Trumbull chaired a Senate Judiciary Committee to merge the different proposals.

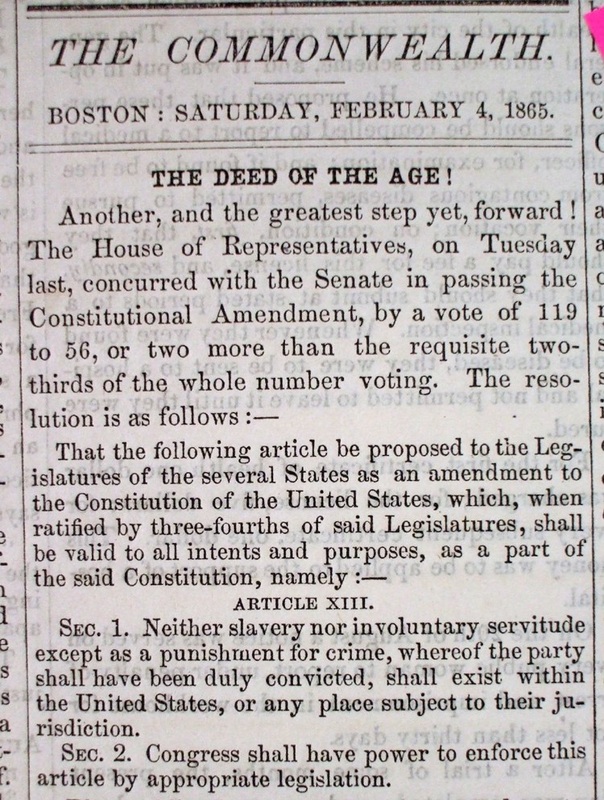

Boston newspaper announces the passage of the 13th Amendment.

On April 8, 1864, the Senate passed the amendment with a vote of 38 to 6, but the House had difficulty getting the necessary two-thirds vote to pass it. While arguments continued in the House, Lincoln grew more concerned about the amendment’s fate. He worried that without the Constitutional amendment, the step forward taken with the Emancipation Proclamation might be lost at the end of the war. After winning a second term in late-1864, Lincoln made the amendment a top priority and encouraged his cabinet to secure votes by any means possible. With the efforts of Lincoln and his team, the House finally passed the 13th Amendment on January 31, 1865 by a vote of 119 to 56. The final wording read:

Neither Slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime; whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

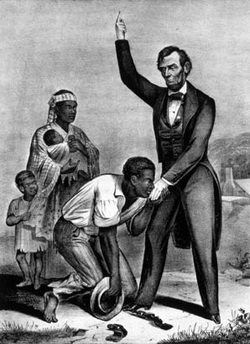

Emancipation and Lincoln's Assassination solidified Lincoln as the "Great Emancipator."

While Lincoln was a force behind emancipation and the 13th Amendment, he did not live to see it come to fruition. The amendment was submitted to the states for ratification on February 1, 1865, but did not receive the three-fourths ratification needed for its passage until December 1865, months after the war’s end and Lincoln’s assassination. Once ratified, the 13th Amendment put power behind the meaning of the Emancipation Proclamation, ensured the abolition of slavery in America, and nullified the pro-slavery passages in the Constitution. As the first of the Reconstruction Amendments, the passage of the 13th Amendment marked the beginning of Reconstruction and the political, economic, and racial restructuring of the country. This amendment cemented the Civil War as a war to end slavery, catapulted the United States into the uncertainty of Reconstruction, and ensured Lincoln’s legacy as the “Great Emancipator.”

Further Reading:

Eric Foner. The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery. W.W. Norton & Company, 2011.

James Oakes. Freedom National: The Destruction of Slavery in the United States, 1861-1865. W. W. Norton & Company, 2014.

James Oakes. The Radical and the Republican: Frederick Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, and the Triumph of Antislavery Politics. W. W. Norton & Company, 2008.

Michael Vorenberg. Final Freedom: The Civil War, the Abolition of Slavery, and the Thirteenth Amendment. Cambridge University Press, 2004.

"The 13th Amendment Passes the House" is the latest post in our Sesquicentennial Spotlight series. As we move through the 150th anniversary of the final year of the American Civil War, Civil Discourse will revisit the major battles and events that shaped the war's conclusion and its legacy. Keep an eye out for further posts in our Sesquicentennial Spotlight series.

Kathleen Logothetis Thompson graduated from Siena College in May 2010 with a B.A. in History and a Certificate in Revolutionary Era Studies. She earned her M.A. in History from West Virginia University in May 2012. Her thesis “A Question of Life or Death: Suicide and Survival in the Union Army” examines wartime suicide among Union soldiers, its causes, and the reasons that army saw a relatively low suicide rate. She is currently pursuing her PhD at West Virginia University with research on mental trauma in the Civil War. In addition, Kathleen has been a seasonal interpreter at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park since 2010 and has worked on various other publications and projects.