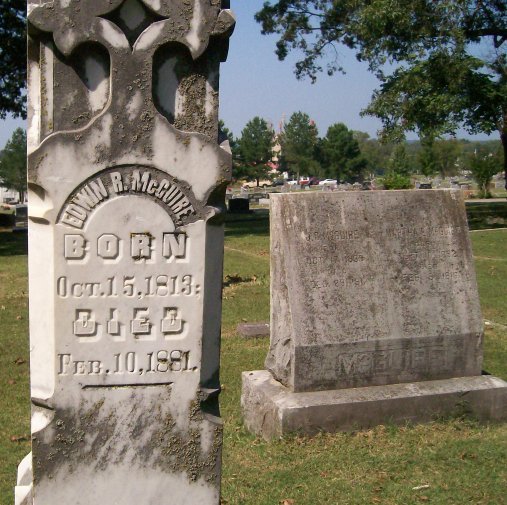

The Plight and Flight of Unionist Edwin R. McGuire: Divided Loyalties and Violence in Independence County, Arkansas

/On Friday, December 4, 1863, Missouri Corporal John Winterbottom recorded in his diary that just days before, “20 Rebels attacked the house of a rich unionist 10 miles West of here, by the name of McGuire. He killed two of the Rebels and then made his escape with a slight wound. The Rebels then burned his house, which was the finest in the country.” Two days later, on Sunday the 6th, two companies of the Third Missouri Cavalry rode out of Jacksonport, Arkansas, accompanied by a wagon train. Crossing the White River, the convoy traveled 10 miles west towards Oil Trough Bottoms, a fertile, low-lying stretch of countryside. Oil Trough was home to Edwin R. McGuire, one of the wealthiest landowners in Northeast Arkansas.

The McGuires now found themselves sudden refugees, and the 3rd Missouri Cavalry sought to escort them to the safety of Union lines. Arriving at burnt ruins of McGuire’s home Sunday evening, the trains were loaded and troopers bedded down for the night. The next day, the motley party returned to Jacksonport through a rainstorm, “bringing with us McGuire’s family, Negros, and all the property they had saved from the fire.”

The plight of Edwin McGuire and his family offers a window into the confused communal politics and military landscape of Independence County, Arkansas during the American Civil War.

Born in 1813 in North Carolina, Edwin Ruthvin McGuire migrated to frontier Arkansas as a young man. Settling in Oil Trough Bottoms in Independence County, McGuire quickly assumed prominence within the community. He was described as a “positive man, decided in his views and opinions; he was outspoken…to a manly form were added a sound mind and a stout heart.” In 1838, he married Emeline Craig, and the couple had four children. In 1852, McGuire assumed trusteeship of the recently-established Oil Trough Academy, a local co-educational school.

A clever land speculator, McGuire amassed a fortune in real estate; the 1850 census estimated his real estate holdings at 12,000, and by 1860 it had increased to $50,000, alongside $25,000 in personal estate value. McGuire also held 24 enslaved persons: 13 males and 11 females ranging in ages from a few months to 86 years old. He was one of the wealthiest men in Northeast Arkansas.

When the Civil War erupted in 1861, the 14,307 white Arkansans in Independence County proved conditional Unionists. They did not rush into secession. When the first Arkansas convention on secession was held in February 1861, approximately 1500 county citizens voted for Unionist delegates against only 300 votes for secessionists delegates. Only following the clash at Fort Sumter and President Abraham Lincoln’s call for troops—both indicating the inevitability of civil war—did Independence County delegates accede to secession.

Even after Arkansas’s official secession of May 6, 1861, however, many in Independence County continued to favor the Union. Over the course of the Civil War, 1,525 men from Independence enlisted in the Confederate Army and 815 enlisted in the United States Army—a clear indication of a strong Unionist minority. In short, like many other Arkansas counties during the Civil War, Independence County experienced political divisions among its inhabitants that would contribute to spiraling violence as the war dragged on.

Edwin McGuire’s personal Unionist leanings were known to his neighbors. A friend described McGuire as a “Union man of Arkansas of intelligence and respectability second to none.” In classic Civil War style, McGuire’s family was not united in their political views; Edwin’s nephew William McGuire enlisted in the 1st Arkansas Cavalry (CS). Despite Edwin McGuire’s contrarian Unionism, he appears to have done relatively little to harm the Confederate cause. Indeed, one small incident offers insight into McGuire’s affability towards fellow secessionist Southerners.

Following their defeat at Pea Ridge in March 1862, Confederate forces began to shift east of the Mississippi. Around mid-March, the 10th Texas Cavalry under Colonel Matthew F. Locke camped in the vicinity of McGuire’s plantation in Oil Trough. The Rebels dubbed their encampment Camp Van Dorn (after General Earl Van Dorn). Nineteen year old Elvena Maxfield, a friend of the McGuires, visited the plantation for nearly two weeks to see Southern soldiers in person. She found the soldiers “some of the nicest kind of men.”

Yet in the low-lying bottomlands, Confederate troops suffered mightily from various illnesses. Elvena wrote: “a great many of the Reg. sick a good many had the measles. There was at one time twenty sick at Mr. McGuire’s.” Another trooper of the 10th Texas complained to his parents, “There are several of our Company sick at the Hospital and on the road. Our Company is not more than 30 or 40 strong…The sickness most prevailing in camp is Measles…They are dying on every hand.”

Edwin McGuire tended to the Confederate sick and dying. “I think that mr. McGuire is one of the kindest men I ever saw,” Elvena gushed in a letter. “[H]e payed [sic] every attention to the sick that a friend could. he would sit up with them and do any & every thing that any one could. The soldiers have cause to bless him.” Despite his loyalty to the Union, McGuire’s actions reveal him as a compassionate man even towards political foes.

Over the course of the war, the United States Army occupied Batesville three times, including the winter of 1863-1864. Federal forces attempted to impose order: administering oaths of loyalty, recruiting Unionist Arkansans to the military, and quashing Rebel guerrillas. Guerrilla warfare constituted the heart of the wartime experience for many in Arkansas. Desperate to stymy Union advances, Confederate authorities encouraged Arkansans to pick up their muskets and resist the Federal foe in small guerrilla bands. While guerrillas did indeed harass Union forces, they often preyed upon their fellow citizens…and as the war wore on, guerrillas were less and less likely to discern friend-from-foe among vulnerable targets. Federal forces, prone to the occasional foraging and pillaging of their own, worsened the situation.

By the winter of 1863, Edwin McGuire’s wealthy plantation constituted a tempting target for marauders. Union forces garrisoned both Batesville in Independence County and Jacksonport in nearby Jackson County. Small bands of Confederate guerrillas prowled the countryside. Sometime in late 1863, McGuire was robbed of $6,000 worth of property by a gang, whether Southern in sympathy or just bandits. Word then spread that Mr. McGuire “was suspected by these horse and nigger stealing worthies of having given some [Union] scouting parties some information.” Whether McGuire actually collaborated with Union scouts is unknown. Perhaps he acted upon his Unionist leanings and helped the U.S. army. Perhaps had little choice in aiding Federal forces. Perhaps he sought recompense for his stolen property. Perhaps he gave no aid at all, and the rumor was simple fiction. Regardless, for his supposed collaboration, McGuire was susceptible to further targeting by guerillas.

On Friday December 4, several dozen armed men—described variously as a “mob of soldiers,” “butternuts,” and “jayhawkers”—rode up to McGuire’s home, demanding they be admitted. Having already been robbed and fearing the mob’s intention, McGuire stoutly refused. Having expected he might “see company,” his double-barrel shotgun was at the ready. No mention is made of his family being present, perhaps another indicator that McGuire foresaw trouble. The armed intruders again demanded McGuire surrender himself or “they would burn the house over his head.” He “firmly replied that he would kill the first man that attempted to enter.”

When the mob broke the doors in, McGuire proved true to his word and emptied both barrels of his gun, killing two of the intruders. A pair of bullets grazed McGuire’s left arm. He then fled, “barefooted and unclad, to a neighbor’s house, where he viewed the burning of his magnificent residence.” Weary and now homeless, McGuire fled towards Jacksonport and reached the safety of Union lines on the morning of Saturday, December 5. The local Union newspaper crowed, “He reached here the next morning and we dressed his wounds, which we are glad to say are not dangerous to him, but we think that left arm of his may prove dangerous to some of them [the intruders] one of these days.

Following Edwin McGuire’s flight, Companies B & G of the 3rd Missouri Cavalry traveled out to Oil Trough on December 6-7, returning with the remainder of McGuire’s family, slaves, and surviving property. McGuire later fled to permanent safety in Missouri.

The plight of Edwin McGuire and his family is illustrative of how guerrilla warfare ensnared citizens in cycles of destruction. McGuire, a peaceable Unionist—who kindly ministered to Rebel sick and dying in March 1862—was charged (rightly or wrongly) with collaborating with Union occupation forces in late 1863. As a result, an armed party of intruders—Confederate guerrillas seeking retribution? bandits seeking wealth?—assaulted McGuire and burned his home. McGuire and his family were quite literally driven into the arms of the Union army. Nor was McGuire alone in his plight; other Independence County Unionists were driven from their homes during the war, while pro-Confederate families fled during periods of Union occupation.

Edwin McGuire recovered financially and socially from the war. The 1870 census shows his personal estate value had plummeted to $500 (from $25,000 10 years prior), but he still held $15,000 in real estate value. As his obituary later admitted, “He was at one time the wealthiest man in north Arkansas, and at other times among the poorest, but no conscious wealth or conscious property seemed to effect the man.” McGuire remained socially prominent, eventually serving as justice of the peace for Independence County. He was an active Freemason, and upon his death, the local chapter was named after him in his honor. The McGuires were upheld as “one of the oldest and most highly respected families in the state and county.”

Interestingly, postwar accounts of the attack on McGuire are devoid of any sectional labels—no mention is made of McGuire’s Unionism or supposed collaboration with Union forces, nor is any specific name given to the “soldiers” who attacked him that December night in 1863. In short, Union and Confederate, North and South are dropped from the story. By conveniently dropping sectional labels, the ugly truth of McGuire’s plight—and indeed, the brutal reality of the war years in Northeast Arkansas—were put to rest in an effort to move on.

Dr. Zac Cowsert teaches history and humanities courses at the Arkansas School for Mathematics, Sciences, & the Arts, a public residential high school in Hot Springs. He holds a PhD in history from West Virginia University, where he also received his master's degree. He earned his bachelor's degree in history and political science from Centenary College of Louisiana in Shreveport. Zac’s dissertation explored the American Civil War in Indian Territory (modern Oklahoma), and his research interests include the Civil War Trans-Mississippi, Southern Unionism, and the interactions between Civil War armies and newspaper presses. ©

Sources & Further Reading

Batesville Guard. April 4, 1878; February 16, 1881; February 23, 1881; March 9, 1881. Batesville, AR. Online.

Stars and Stripes. December 8, 1863. Batesville, AR. [Newspaper of the 3rd Missouri Cavalry]

Bailey, Anne J. and Daniel E. Sutherland, eds. Civil War Arkansas: Beyond Battles and Leaders. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

Biographical and Historical Memoirs of Northeast Arkansas. Chicago, IL: Goodspeed Publishing Co., 1889. Available via Google Books.

Byers, Mary Adelia. Torn By War: The Civil War Journal of Mary Adelia Byers. Edited by Samuel R. Phillips. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2013.

Christ, Mark K., ed. Rugged and Sublime: The Civil War in Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1994.

Crowley, William J. Tennessee Cavalier in the Missouri Cavalry: Major Henry Ewing, C.S.A., of the St. Louis Times. Columbia, MO: Kelly Press, 1978.

Griffith, Nancy. “Oil Trough (Independence County),” Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Online.

James Henry Lauriston Hull, 10th Texas Cavalry, Civil War Letter Collection. Transcribed by J. Brinkoeter. Online.

James, Nola A. “The Civil War Years in Independence County.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly. Vol. 28, No. 3 (Autumn, 1969): 234-274.

Mobley, Freeman K. Civil War! A Missing Piece of the Puzzle: Northeast Arkansas, 1861-1874. Batesville, AR: 2010.

Petty, A. [Alexander] W.M. A History of the Third Missouri Cavalry: From Its Organization at Palmyra, Missouri, 1861 up to November Sixth, 1864. Little Rock: J. Wm. Pemby, 1865. Available via Google Books.

Sutherland, Daniel E. A Savage Conflict: The Decisive Role of Guerrillas in the American Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009.

Winterbottom, John Sebastian. “The Civil War Diary of John Sebastian Winterbottom.” Edited by Carol L. Huber. Missouri State Parks, 2011. Available via the Battle of Pilot Knob State Historic Site.