Chasing Bushwhackers: The 3rd Missouri Cavalry and a "Scout to Hot Spring County," Arkansas

/On February 8, 1864, blue-clad troopers of the 3rd Missouri Cavalry rode southwest out of Little Rock, Arkansas on a “scout to Hot Spring County…for the purpose,” explained Private Alexander W.M. Petty, “of driving out a company of bushwhackers reported to be committing all kinds of depredations there upon the persons and property of the loyal citizens.” Over the next week, the Federals journeyed over 200 miles, clashed repeatedly with Rebel guerrillas, suffered casualties, and took enemy prisoners. Their scout through Southwest Arkansas—typical of the countless small counterinsurgency expeditions and clashes with Rebel bushwhackers that infested the Ozarks and Ouachitas—offers a window in the harsh realities of guerrilla warfare and the difficulties that faced U.S. soldiers in attempting to suppress it.

The Civil War ravaged Arkansas. In the early years of the war, Union and Confederate forces clashed repeatedly in the northern part of the state, hoping not only to secure Arkansas but also Missouri to the north. Decisive Union victories at Pea Ridge in March and Prairie Grove in December of 1862 ended Confederate hopes of ever permanently occupying Missouri. Moreover, these victories made the invasion of central Arkansas a true threat. In 1863, Union forces campaigned to secure the Arkansas River Valley stretching through the very center of Indian Territory and Arkansas. Federal victories at Honey Springs, Bayou Fourche, and elsewhere collapsed the Confederacy’s Arkansas River defenses. By autumn of 1863, Old Glory floated over Fort Gibson, Fort Smith, and Little Rock, forcing Confederate forces into small footholds in the southern portion of Arkansas.

While these military campaigns determined the military and political fate of “Rackensack,” as Arkansas was sometimes called, increasing guerrilla violence shaped the everyday lives of many more Arkansans. As historian Daniel Sutherland eloquently argues: “This is how the Civil War was fought in Arkansas: ambushes, midnight raids, often with civilians treated as combatants and neighbors turned predators.” In the Boston and Ouachita Mountains of western Arkansas, Rebel guerrillas preyed on Unionist families, isolated Federal outposts, and the occasional innocent traveler. Guerrillas infested the counties to the southwest of Little Rock: Saline, Montgomery, and Hot Spring. Guerrilla activity forced many families to flee their homes altogether; by late 1863, the small village of Hot Springs—famous then and now for its warm, natural thermal springs and after which Hot Spring County was named—was almost entirely deserted.

Having conquered Little Rock and the Arkansas River Valley, local Union forces shifted much of their attention into bolstering Unionist sentiment and suppressing Confederate guerrilla activity. In January 1864, a provisional, pro-Union government was installed in Little Rock, with Unionist Isaac Murphy made provisional governor. A new constitution was adopted that nullified secession and abolished slavery. Yet public support for the provisional government, to be ratified by formal vote in March, demanded the Union quash, or at least contain, Rebel bushwhackers. Union patrols routinely scoured Central Arkansas in search of guerrillas.

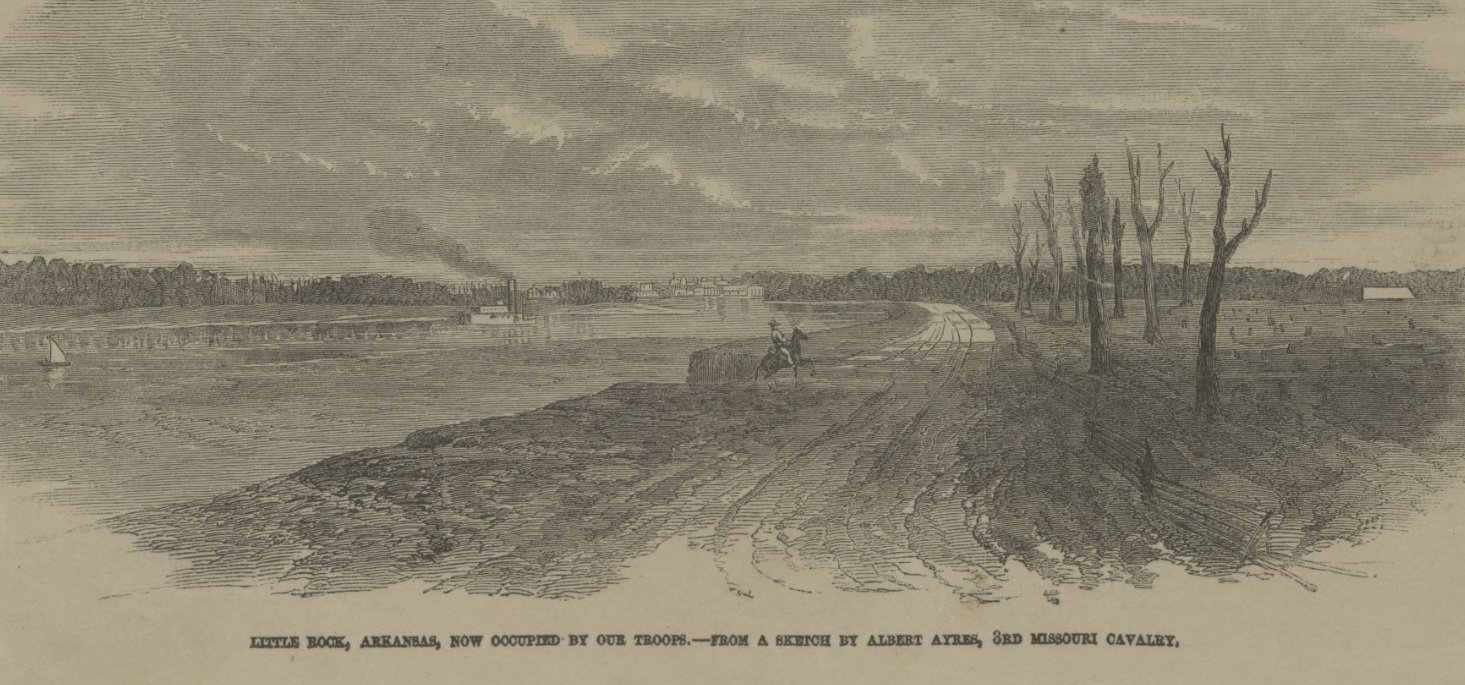

A Sketch of Little Rock by Albert Ayres of the 3rd Missouri Cavalry. (Courtesy of the Central Arkansas library System)

The hard-bitten troopers of the 3rd Missouri were longtime veterans of such counter-insurgency activities. The regiment was raised in the summer of 1861 and entered service that winter; many of its men actually hailed from nearby Illinois, although plenty of Missourians also filled out the ranks. The regiment was immediately tasked with combating guerrillas in southern Missouri, and over the following two years, the troopers scoured the piney woods and Ozark hollows of Arkansas and Missouri. They participated in the Federal expedition that captured Little Rock in September 1863. And it was from Little Rock that the Illinoisans and Missourians departed for yet another scouting expedition into the countryside in February 1864.

Somewhat unusually, the Official Records of the War the Rebellion—the first go-to source for military historians—acknowledges that an expedition towards Hot Springs took place but contains no official report. Thus, nearly everything we know about the affair comes from the writings of Private Alexander W.M. Petty, a 22 year-old private of Company I. Petty apparently kept a journal during the war; in 1865, at the behest of his fellow comrades-in-arms, he published his History of the Third Missouri Cavalry in Little Rock. A few supporting details of the raid are also found in Quartermaster Sergeant John Sebastian Winterbottom’s diary, available courtesy of Missouri State Parks. From these sources we can reconstruct the scout’s events in early February.

Led by Captain John H. Reed, the opening phase of scout proved relatively uneventful. The Federal troops left Little Rock and ventured west, passing through the northern stretch of Hot Spring County and into Montgomery County. Upon reaching Cedar Glades (also known as Harold Post Office) in eastern Montgomery County, the troopers made camp. While resting, the 3rd Missouri’s pickets briefly skirmished with the enemy, which “had the effect of making the men comprising the scout keep a lookout for the future.” The Federal forces continued westward, crossing the Ouachita River and “capturing some few contraband horses, etc.”

Having accomplished little, the troopers turned back to return to Little Rock, “despairing of having an opportunity offered [denied] them for battle with the enemy except some small skirmishes.” The Federals would soon get their wish, however; things were about to get lively. Moving eastward through the hills near the North Fork of the Saline River, the Federal troopers were ambushed by nearly 100 Confederate guerrillas “who had taken a concealed position on the bluffs that flanked our party on both sides.” The initial sharp burst of gunfire wounded three troopers along with several horses. Sergeant William Henry Clyma’s horse fell dead beneath him, pierced by four shots. Fortunately, Clyma himself escaped unharmed, an undoubted relief to his wife and seven children back home in Monticello, Wisconsin.

Having sprung their ambush, the guerrillas quickly dispersed into the woods in true hit-and-run fashion. Determined to prevent their escape, Captain Reed ordered Captain John D. Crabtree to take Company M and charge the fleeing foe. Rushing forward into the forest, Reed’s troopers closed in around several bushwhackers, including the Rebel commander whose name was “Aikens.”

“This man [Aikens] fought desperately,” reported Petty. “Throwing himself behind a tree, he fired the contents of two revolvers at the captain and his party ere he would consent to surrender.” Struck by the Rebel chieftain’s bravery, Captain Crabtree determined to take him alive. The Federals succeeded in nabbing Aikens along with at least two more guerrilla prisoners. Further searches for the remaining guerrillas—doubtless long since fled—proved fruitless, and the 3rd Missouri Cavalry resumed their return to Little Rock, arriving in the city around 2 a.m. on Monday, February 15th. According to Sergeant Winterbottom, the troopers had endured eight days in the field and “traveled over 200 miles. They were Bushwhacked six times in the mountain passes.” Winterbottom also reported that the Missourians burned a number of houses during their expedition, a detail Petty neglects to mention. Both Petty and Winterbottom agree that three Union troopers were wounded; Petty also records that five men of the 3rd Missouri were captured by the enemy during the expedition.

Despite terrorizing Union citizens in the area and coordinating the ambush of the 3rd Missouri near the Saline River, the guerrilla leader “Aikens” remarkably escaped serious punishment. Petty indignantly recorded that Aikens was taken to the Federal provost marshal in Little Rock. Apparently, a number of local citizens spoke on Aikens’ behalf, and the provost marshal allowed Aikens to take an oath of allegiance to the United States in return for his freedom. “We subsequently learned he reorganized his chivalrous band of cut-throats, murderers, and assassins,” Petty angrily reported, “and soon again was engaged in the very laudable enterprise of robbing helpless women and children, hanging and shooting old grey headed citizens, for no other cause than they were loyal to the Federal government.”

This 1864 map of Arkansas shows the route of the 3rd Missouri’s Scout: West from Little Rock through Saline County and Hot Spring County to Harold’s Post Office (Cedar Glades), across the Ouachita River (misspelled here as “"Washita”) then back through the hills bordering the north fork of the Saline River. (Courtesy of LOC)

Who was this fortunate “Aikens”? Determining the identity of any guerrilla is often a tall task (both then for the soldier, and now for the historian). No records I’ve uncovered definitively reveal “Aikens” identity, but I’ll hazard putting forth a possible candidate.

Northern Hot Spring County was home to a small post office known as Akin’s Store. Established by Edward Akin in the 1830s, the store sat right along the road travelled by the 3rd Missouri Cavalry and was near the area of the guerrilla ambush. Born in 1808, Edward Akin likely would’ve been too old to take to the brush as a guerrilla during the Civil War.

Edward had several sons, however, including Samuel L. Akin. Samuel enlisted in the 2nd Arkansas Infantry Battalion at Hot Springs in September 1861 and saw service in the Eastern Theater. Suffering intense casualties in the Seven Day’s Campaign, the 2nd Arkansas Battalion was lauded by General Robert E. Lee for its sacrifice. In Special Order 152 of July 18, 1862, Lee specifically mentioned all the battalion’s survivors by name, including “S.L. Aiken.” Although the 2nd Battalion was folded into its fellow 3rd Arkansas Infantry, Akin did not transfer and disappears from Confederate records. In July 1863, he and his wife Elizabeth had their first child Frances, corroborating his return home.

Could Samuel L. Akin have been the notorious guerilla leader “Aiken”? Given his family’s proximity and prominence within the area and his military experience, Samuel Akin makes a plausible candidate. Edward Akin died in June 1864; family lore holds that Edward was slain at the hands of “bushwhackers” (whether Union or Confederate is unclear) and that his family sought revenge and killed his assassins. Samuel L. Akin died a month later in 1864 at age 26; nothing is known about his death. Could these untimely deaths hint at a deeper connection to local guerrilla violence? Perhaps, but we will likely never know.

Ultimately, the 3rd Missouri Cavalry’s February 1864 scouting expedition stands as a perfect example of the frustrating efforts by the United States military to quash Confederate guerrilla activity during the Civil War. Reports of Unionist Arkansans being harried by guerrillas spurred the expedition, but of course by the time of the 3rd Missouri’s arrival in the area, the bushwhackers had all but disappeared. Resorting to securing wayward horses and burning homes, the frustrated Missourians seemed to have accomplished little.

The classic guerrilla ambush near the Saline River typifies the types of hit-and-run attacks that inflicted a steady trickle of casualties on Union forces and hardened Federal soldiers’ attitudes towards guerrillas they perceived as “cut-throats, murderers, and assassins.” The few prisoners taken must have seemed like a poor prize for their efforts, especially given the mysterious Aikens’ quick release in Little Rock. For the veteran troopers of the 3rd Missouri and many other soldiers of the Union Army, scouring the enemy countryside and clashing with guerrillas must have seemed a tough, grueling affair, and expeditions like that of February 1864 were common scenes throughout the mountainous South.

A Civil War historian, Dr. Zac Cowsert holds a PhD in history from West Virginia University, where he also received his master's degree. He earned his bachelor's degree in history and political science from Centenary College of Louisiana in Shreveport. Zac’s dissertation explored the American Civil War in Indian Territory (modern Oklahoma), and his research interests include the Civil War Trans-Mississippi, Southern Unionism, and the interactions between Civil War armies and newspaper presses. ©

Sources & Further Reading

Bailey, Anne J. and Daniel E. Sutherland, eds. Civil War Arkansas: Beyond Battles and Leaders. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

Christ, Mark K., ed. Rugged and Sublime: The Civil War in Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1994.

Mackey, Robert R. The Uncivil War: Irregular Warfare in the Upper South, 1861-1865. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2004.

Petty, A. [Alexander] W.M. A History of the Third Missouri Cavalry: From Its Organization at Palmyra, Missouri, 1861 up to November Sixth, 1864. Little Rock: J. Wm. Pemby, 1865. Available via Google Books.

Richter, Wendy. “The Impact of the Civil War on Hot Springs, Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 43:2 (Summer 1984): 125-142.

Sutherland, Daniel E. A Savage Conflict: The Decisive Role of Guerrillas in the American Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009.

Sutherland, Daniel E., ed. Guerrillas, Unionists, and Violence on the Confederate Home Front. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1999.

Williams, Charles G. “A List of Confederate Citizen Prisoners Held at the US Military Prison at Little Rock, Arkansas.” Pulaski County Historical Review 36 (Winter 1988): 93-95.

Winterbottom, John Sebastian. “The Civil War Diary of John Sebastian Winterbottom.” Edited by Carol L. Huber. Missouri State Parks, 2011. Available via the Battle of Pilot Knob State Historic Site.