"Grant is beating his head against a wall": Lt. Col Walter Taylor on the Overland Campaign

/In preparation for a week-long visit to various central Virginia Civil War battlefields, I’ve been reviewing the writings of various military participants. Over at the Civil War Monitor, Gary Gallagher recently recommended a variety of writings essential to understanding the Army of Northern Virginia. Included in his list was the correspondence of Lieutenant Colonel Walter Taylor, who served as General Robert E. Lee’s aide-de-camp throughout the Civil War.

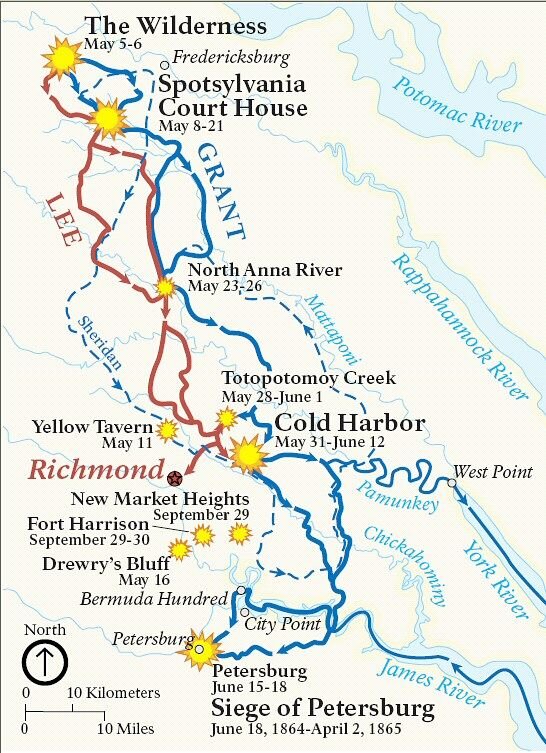

With Gallagher’s recommendation in mind, I reviewed Walter Taylor’s writings on the critical 1864 Overland Campaign. The first clash between Ulysses S. Grant & Robert E. Lee, Grant spent the summer of 1864 tirelessly working to overrun the Confederacy via simultaneous military offensives and to bring Robert E. Lee to bear in a decisive, open-field battle. The result was nearly two months of continual combat, including devastating clashes at the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Court House, North Anna River, Totopotomoy Creek, and Cold Harbor.

Taylor’s writings offer an invaluable window into morale and thoughts of the Confederate high command throughout the summer. They likewise reveal Confederates’ ultimate faith in Robert E. Lee and disdain for Ulysses S. Grant. I’ve compiled several critical passages from Taylor’s writings. These passages come from two sources: Walter Taylor’s wartime correspondence to friends and family (which are dated), as well as his 1877 post-war memoir Four Years with General Lee (which I’ve labeled as excerpts). At the conclusion, I’ve offered some thoughts on Taylor’s invaluable insights into the campaign.

March 4, 1864, Camp Orange County

“My chief [Lee] is first rate in his sphere—that of a commanding general. He has what few others possess, a head capable of planning a campaign and the ability to arrange for a battle, but he is not quick enough for such little affairs as the one I have described. He is too undecided, takes too long to form his conclusions. He must have good lieutenants, men to move quickly, men of nerve such as Jackson. With such to execute and the Genl to plan, we could accomplish anything within the scope of human powers.”

March 20, 1864

“As far as I can judge from the latest papers we have from the North, it appears to be their intention to place Sherman where Grant now is and either to have the latter on duty as Commandr in Chief in Washington with Halleck as Chief of Staff, or to place him at the head of the army of the Potomac. In either position I do not think he is to be feared. He has been much overrated and in my opinion, I am sorry to say, owes more of his reputation to Genl Pemberton’s bad management than to his own sagacity and ability. He will find, I trust, that General Lee is a very different man to deal with & if I mistake not will shortly come to grief if he attempts to repeat the tactics in Virginia which proved so successful in Mississippi.”

April 3, 1864, Camp Orange County

“The General [Lee] called me into his tent this afternoon to talk over some matters, and after discussing several things all relating to Grant’s movements & probable intentions he said ‘but Colo we have got to whip them, we must whip them and it has already made me better to think of it.’ He had been complaining somewhat and it really seemed to do him good to look forward to the trial of strength soon to ensue between himself & the present idol of the North. Our army increases daily. In morale & discipline its condition is excellent. We are taking the necessary steps to put the ‘concern’ in fighting trim—reducing baggage—getting up horses—etc. Have entirely suspended leaves to officers and all begins to look like work. I am very hopeful, feeling confident that with God’s help, we will defeat their last great effort & make this the last year of serious fighting.”

May 1, 1864, Camp Orange County

“Burnside has joined Grant. It will take them perhaps three or four days to get matters into shape for an attack. At any day after that period, we will not be surprised to hear that the last ‘onward’ has commenced. Grant may perhaps managed to get together seventy or eighty thousand men—the latter figure will, I think, cover every man he has or will have for this battle. If all our army is placed under Gl [General] Lee’s control, I have no fear of the result. Even as matters now stand, with the help of God, we will render the usual good account of victory. I am deeply impressed with the vast importance of success in this campaign. If Grant’s army is demolished, I don’t think there is a doubt but that peace will be declared before the end of the year. If we are defeated, which may a Kind Providence prevent, then the war must dragon on a year or so longer. Oh how earnestly should our people pray for God’s help in this emergency.”

Excerpt from Four Years with Lee Regarding the Battle of the Wilderness

“Much hard fighting ensued: for two days there was a murderous wrestle; severe and rapid blows were given and received in turn, until sheer exhaustion called a truce, with the advantage on the Confederate side. Notably was this the case in a brilliant assault made by General Longstreet on the Federal left on the 6th of May; and in a turning movement on their right on the same day, executed by a portion of General Ewell's (Second) corps—the brigades of Gordon, Johnston, and Pegram—doubling up that flank and forcing it back a considerable distance…

The Third Division of Hill's (Third) corps, tinder General Anderson, and the two divisions of Longstreet's (First) corps, did not reach the scene of conflict until dawn of day on the morning of the 6th. Simultaneously the attack on Hill was renewed with great vigor. In addition to the force which he had so successfully resisted the previous day, a fresh division of the Fifth Corps, under, General Wadsworth, had secured position on his flank, and cooperated with the column assaulting in front. After a short contest, the divisions of Heth and Wilcox, who had expected to be relieved, and were not prepared for the enemy's assault, were overpowered and compelled to retire, just as the advance of Longstreet's column reached the ground. The defeated divisions were in considerable disorder, and the condition of affairs was exceedingly critical. General Lee fully appreciated the impending crisis, and, dashing amid the fugitives, personally called upon the men to rally. General Longstreet, taking in the situation at a glance, was prompt to act—immediately caused his divisions to be deployed in line of battle, and gallantly advanced to recover the lost ground.

The soldiers, seeing General Lee's manifest purpose to advance with them, and realizing the great danger in which he then was, called upon him in a beseeching manner to “go to the rear,” promising that they would soon have matters rectified, and begging him to retire from a position in which his life was so exposed. The general was evidently touched and gratified at this manifestation of interest and anxiety on the part of his brave men, and waved them on, with some words of cheer. Their advance under such circumstances was simply irresistible; every man felt that the eye of the commanding general was upon him, and was proud of the opportunity of showing him that his trust in his men was not misplaced. The Federal advance was checked, and the Confederate lines reestablished.”

May 15, 1864, Near Spotsylvania Courthouse

“We have had some very severe fighting & a great deal of one kind & another. With one single exception, our encounters with the enemy have been continuously & eminently successful. In the Wilderness we enjoyed several victories over vastly superior numbers—on arriving here we were blessed with signal success. After we were established here, the enemy attacked every portion of our lines at different times, and with one exception mentioned, were invariably handsomely repulsed & severely published. The 12th was an unfortunate day for us—we recovered most of the ground lost but cd not regain our guns. This hurts our pride—but we are determined to make our next success all the greater to make amends for this disaster. Our men are in good heart & condition—our confidence, certainly mine, unimpaired. Grant is beating his head against a wall. His own people confess a loss of 50,000 thus far.”

Excerpt from Four Years with Lee Regarding the Battle of Spotsylvania Courthouse

“Upon an examination of the lines, General Lee had detected the weakness of that portion known as ‘the salient,’ to the right of the point assailed on the 10th, to which I have just alluded, and occupied by the division of General Edward Johnson (Ewell's corps), and had directed a second line to be constructed across its base, to which he proposed to move back the troops occupying the angle. These arrangements were not quite completed, when he thought he saw cause to suspect another flank-movement by General Grant, and, on the night of the 11th, ordered most of the artillery at this portion of the lines to be withdrawn, so as to be available to take part in a counter-movement.

Toward the dawn of day, on the 12th, General Johnson discovered indications of an impending assault upon his front. He sent immediate orders for the return of his artillery, and caused other preparations for defense to be made; but the enemy, who could advance without discovery to within a short distance of the works under cover of a body of woods, had massed there a large force, and, with the advent of the first rays of morning light, by a spirited assault, quickly overran that portion of the lines before the artillery could be put in position, and captured most of the division, including its brave commander. The army was thus cut in twain, and the situation was one well calculated to test the skill of its commander and the nerve and courage of the men. Dispositions were immediately made to repair the breach, and troops were moved up from the right and left to dispute the further progress of the assaulting column. Then occurred the most remarkable musketry-tire of the war: from the sides of the salient, in the possession of the Federals, and the new line, forming the base of the triangle, occupied by the Confederates, poured forth, from continuous lines of hissing fire, an incessant, terrific hail of deadly missiles. No living man nor thing could stand in the doomed space embraced within those angry lines; even large trees were felled—their trunks cut in twain by the bullets of small-arms. Never did the troops on either side display greater valor and determination. Intense and bitter was the struggle.

The Confederates, moving up to fill the gap, fell with tremendous power upon the Federal mass, caused it to recoil somewhat, closed with it in a hand-to-hand conflict, but failed to dislodge it; while the Federal assault, which threatened such serious consequences, was effectually checked, and the advantage to the enemy resulting therefrom was limited to the possession of the narrow space of the salient and the capture of the force which had occupied it. The loss of this fine body of troops was seriously felt by General Lee; but sadly reduced though his army was, by this and a week's incessant fighting, such was the metal of what remained that his lines, thus forcibly rectified, proved thereafter impregnable.”

May 23, 1864, Telegraph Road, Camp Hanover Junction

“For the first time since the 4th of this month, I on yesterday was spared the sight of the miserable Yankees…He dared not, as we prayed he wd, attack us again at Spottsylvania. With several rivers between us he could move to Bowling Green and below without any danger of our intercepting him. He wd thus get some miles nearer Richmond in a geographical sense, but in reality he was as far from it as ever, because this army will still confront him, let him change his base as often as he pleases…Why Grant did not carry his army to his new base without incurring the heavy losses he has sustained in battle I can not say. If Fredericksburg was his destination he cd have obtained possession of it without the loss of 100 men. The same can be said of West Point. After his whipping in the Wilderness, he started for Spottsylvania C.H. hoping to reach there before Genl Lee. There were but few indications of his departure from our front at that time, but Gl Lee seemed to divine his intention & sent a corps to Spottsylvania just in time to meet the enemy at that place. We engaged & beat them back thereby securing Spots. C.H. As the result of this, the Northern papers say we retreated & Grant pursued us, whereas he was totally outgeneraled. No doubt the whole Yankee nation is this day glorying over our retreat to this place. Yet the battlefield was left in our possession & we marched here without any molestation whatever.

This does not look like a retreat. Our army is in excellent condition—as good as it was when we met Grant, two weeks since for the first time. He will feel us again before he reaches his prize. His losses have been already fearfully large. Our list of casualties is a sad one to contemplate, but does not compare with his terrible record of killed and wounded; and the man is such a brute, he does not pretend to bury his dead, leave his wounded without proper attendance, & seems entirely reckless as regards the lives of his men. This and his remarked able pertinacity are the only qualifications he has exhibited, which differ in any way from those of his predecessors. He certainly holds on longer than any of them. He alone of all would have remained this side of the Rappahannock after the battle of the Wilderness. This may be attributable to his nature, or it may be because he knew full well that to relinquish his designs on Richmond, even temporarily, wd forever ruin him & bring about peace. This is, I think, sure his last campaign.”

Early Morning, May 30, 1864, Camp Atlee’s Station

“The Genl [Lee] has been somewhat indisposed & cd attend to nothing except what was absolutely necessary for him to know & act upon & during the past week my cares have been thereby increased. He is now improving. I had half a notion to get sick myself, but his attack frightened all sickness away from me.”

June 1, 1864

“Since the General’s indisposition he has remained more quiet & directs movements from a distance. This is as it should be, if we had capable lieutenants ‘tis the course he might always pursue…We are in good condition. By the way, think nothing about our numerical weakness when compared to Grant’s army. Recently we recd something less than several thousand reinforcements and have plenty of men to manage the enemy.”

June 9, 1864, Camp (near Cold Harbor)

“I have not heard a gun today, nor did I hear many during the night. I presume Grant is waiting for further developments in the Valley. Plague that force at Staunton say I. I fear it will be increased & prove troublesome to us. But though apparently about to be sorely pressed, I doubt not the good God who has always shielded us, will provide a way of defence and bring us safely through our trials.”

Excerpt from Four Years with Lee Regarding the Battle of Cold Harbor & Beyond

“…The two armies again gravitated east, and were soon (June 3d) face to face on the historic field of Cold Harbor. Here, gallant but fruitless efforts were made by General Grant to pierce or drive back the army under General Lee. The Confederates were protected by temporary earthworks, and while under cover of these were gallantly assailed by the Federals. But in vain: the assault was repulsed along the whole line, and the carnage on the Federal side was frightful. I well recall having received a report after the assault from General Hoke—whose division reached the army just previous to this battle—to the effect that the ground in his entire front, over which the enemy had charged, was literally covered with their dead and wounded; and that up to that time he had not had a single man killed. No wonder that, when the command was given to renew the assault, the Federal soldiers sullenly and silently declined to advance. After some disingenuous proposals, General Grant finally asked a truce to enable him to bury his dead. Soon after this he abandoned his chosen line of operations, and moved his army to the south side of James River. The struggle from the Wilderness to this point covered a period of over one month; during which time there had been an almost daily encounter of hostile arms, and the Army of Northern Virginia had placed hors de combat of the army under General Grant a number equal to its entire numerical strength at the commencement of the campaign, and, notwithstanding its own heavy losses and the reenforcements received by the enemy, still presented an impregnable front to its opponent, and constituted an insuperable barrier to General Grant's “On to Richmond!”

After an unsuccessful effort to surprise and capture Petersburg—which was prevented by the skill of Generals Beauregard and Wise, and the bravery of the troops, consisting in part of militia and home-guards—and a futile endeavor to seize the Richmond & Petersburg Railroad, General Grant concentrated his army south of the Appomattox River. General Lee, whom he had not been able to defeat in the open field, was still in his way, and the siege of Petersburg was begun.”

What do Taylor’s writings, both during and after the war, reveal about the 1864 Overland Campaign? A few dominant takeaways stick out:

Confederates retained great faith in Robert E. Lee throughout the campaign.

Throughout his writings, Taylor consistently places firm faith that Lee will lead the Army of Northern Virginia to victory. “If all our army is placed under Gl [General] Lee’s control, I have no fear of the result.” Even after the bloodshed of the Wilderness (where the Federals were given a “whipping” according to Taylor) and Spotsylvania, followed by Lee’s move south, Taylor continued to believe Lee the superior commander who had “outgeneraled” his foe. Taylor’s views on Lee reflected those of many not only in the Army of Northern Virginia, but throughout the Confederacy. Though costly engagements, Confederates generally believed they were getting the better of the fighting that summer.

Confederates viewed Grant as merely another Union general to be held in contempt.

Taylor writes of Grant with considerable disdain. Prior to the campaign’s start, Taylor suggests Grant owed his stature to the inferiority of commanders whom Grant faced out west, such as General John C. Pemberton at Vicksburg. (Ironically, this charge could also be placed against Lee, who had fared well against a slate of overly-defensive or overly-confident commanders in the East.) Grant was '“overrated.” As the campaign wore on, Taylor adopted the view that Grant was waging a losing campaign but was either too aggressive or too afraid to end it lest he be removed from command. Taylor predicted it would be Grant’s “last campaign.” In Taylor’s writings, we can already see the beginnings of the Lost Cause interpretation of “Grant the Butcher,” who merely threw bodies at Lee and the Confederacy until victory was secured. In reality, Grant desperately wanted to avoid a war of attrition and bring Lee to heel in open battle. (And it is a testament to Lee that he prevented an open battle on unfavorable terms.)

Robert E. Lee struggled with the reliability and performances of his corps commanders throughout the campaign.

It’s clear that Taylor believed that Lee’s “lieutenants” (i.e. corps commanders) failed to successfully carry out their duties. Taylor’s letter of March 4 notes that while he considers Lee a great “commanding general,” Lee falls short of the qualities needed to manage the details of a battle. For Taylor, qualities such as decisiveness and resolve were necessary among Lee’s corps commanders. “He must have good lieutenants, men to move quickly, men of nerve such as Jackson.” Although he never directly criticizes Lee’s corps commanders (Longstreet/Anderson, Hill, & Ewell/Early) by name, implicit in his writing is that Lee’s lieutenants are lacking (hence his almost mournful references to the departed “Stonewall” Jackson). To a certain extent, this criticism of Taylor’s is fair. Longstreet was undoubtedly Lee’s most experienced and reliable corps commander, but his wounding at the Wilderness removed him from the campaign early. Hill and Ewell proved unreliable throughout the campaign, and J.E.B. Stuart would die following a clash at Yellow Tavern in May. Lee was thus fighting arguably the most important campaign of his career with a questionable high command in a state of flux.

Lee was ill during the campaign.

Taylor’s letters make clear that Lee was ill and “indisposed” around the time of North Anna River. Lee had medical issues with his heart, and the first three weeks of May were some of the most trying in the war for him thus far (as Taylor’s account of the Wilderness “Lee to the Rear” incident indicates). While the Confederacy perhaps held an opportunity to strike at a divided Union army around North Anna River in late May, Lee’s illness may have contributed to the lack of any serious offensive. (It’s worth noting that modern scholars like Mark Grimsley have questioned whether any North Anna River offensive would’ve achieved much…so we shouldn’t get too carried away with “what ifs” here.)

Confederate leaders failed to understand the importance of Ulysses S. Grant’s “pertinacity.”

Following clashes at Wilderness and Spotsylvania, Grant changed his line of operations, shifting southeast in hopes of moving around Lee’s right flank. Taylor didn’t understand this maneuver: “Why Grant did not carry his army to his new base without incurring the heavy losses he has sustained in battle I can not say.” As he rightly points out, Grant could have taken that line of operations from the campaign’s start without losing a man. What Taylor (and Lee) failed to recognize was that Grant’s objective was not simply advancing southward to take Richmond, but rather Grant’s objective was Lee’s army itself. Bases of operation and lines of advance only mattered to Grant insofar as it allowed him to force Lee into open battle.Similarly, Taylor’s critique of Grant as a butcher too ignorant or proud to admit defeat glosses over the strategic reality that Grant’s seizure of the initiative and constant offensives were, in fact, grinding down Lee’s army. While Taylor scorned Grant’s “pertinacity,” this trait made Grant a threat to the Army of Northern Virginia unlike any before. Although Taylor didn’t recognize the danger of Grant’s stubborn offensive at first, Lee recognized the danger in time. “We must destroy this army of Grant’s before he gets to the James River,” Lee worried. “If he gets there, it will become a siege, and then it will be a mere question of time.” Although a war of attrition wasn’t want Grant wanted, it nevertheless proved a successful military strategy; Grant was not, in Taylor’s words, “overrated.”

Ultimately, as Robert E. Lee’s aide-de-camp and a consistent correspondent throughout the war, Walter Taylor’s writings provide an invaluable window into the thinking of Confederate high command during the Overland Campaign. Taylor’s writings suggest a confident Army of Northern Virginia that viewed Lee as nearly infallible and held Grant in low regard, even as the bloody campaign wore on. Taylor and others failed to understand the significance of Grant’s offensive perseverance, instead seeing Grant as an overly-proud butcher. They were in time proven wrong. Taylor’s writings also indicate that despite the high morale of the army and their faith in Lee, questions about the reliability and skill of Lee’s corps commanders lurked, as did Lee’s health itself in late May.

Taylor’s writings also remind us of the importance of moving forward through time as we explore history. While we know Grant and the Army of the Potomac were headed for ultimate victory, in the summer of 1864, many Confederates believed firmly in future success. As Taylor himself wrote, “I am very hopeful, feeling confident that with God’s help, we will defeat their last great effort & make this the last year of serious fighting.”

A Civil War historian, Dr. Zac Cowsert holds a PhD in history from West Virginia University, where he also received his master's degree. He earned his bachelor's degree in history and political science from Centenary College of Louisiana in Shreveport. Zac’s dissertation explored the American Civil War in Indian Territory (modern Oklahoma), and his research interests include the Civil War Trans-Mississippi, Southern Unionism, and the interactions between Civil War armies and newspaper presses. ©

Sources & Further Reading

Mark Grimsley. And Keep Moving On: The Virginia Campaign, May-June, 1864. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

Walter H. Taylor. Four Years with General Lee. New York: Appleton & Co., 1877. Available online.

Walter H. Taylor. General Lee: His Campaigns in Virginia, 1861-1865. 1906. Reprint. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1994.

Walter H. Taylor. Lee’s Adjutant: The Wartime Letters of Colonel Walter Herron Taylor, 1862-1865. Edited by R. Lockwood Taylor. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1994.