Private Uriah "Duck" Alley: The Story of West Virginia's Last Civil War Veteran

/In May 1944, four men stood together for a photograph in the small town of Cameron, West Virginia. On the far left stood Donald Solomon Redd, a veteran of World War II. On his right stood Charles Everett Anderson, a WWI veteran, and Robert Calvin Yoho, who had fought in the Spanish American War. And on the far right side of the remarkable photograph stood 95-year-old Uriah Talmage Alley, affectionately known to many as “Uncle Duck.” Uriah Alley was West Virginia’s last Civil War veteran. The photograph ran in the May 22, 1944 issue of Life magazine, and as the four generational photograph of American veterans suggests, Uriah Alley’s life proved quite a story.

Uriah Alley was born on November 18, 1847 in Cameron, Marshall County, (West) Virginia to John “Jack” and Margaret Alley. Jack Alley was a farmer and Methodist minister, who enjoyed a degree of prosperity (possessing $2,500 in real estate in 1860). Jack Alley, who had been married once before, had eight children, the youngest of whom was Uriah Talmage Alley.

As the Civil War erupted in 1861, Marshall County—like many counties in western Virginia—disdained secession and largely remained loyal to the United States. In December of 1861, Uriah’s older brother William “Leep” Alley journeyed to Mannington and enlisted in Company L, 6th (West) Virginia Infantry. The 6th spent much of the war guarding railroads and chasing Rebel guerrillas in north-central West Virginia, a luckless, thankless task. Leep’s personal record mirrored the plaintive service of his regiment; he suffered from illness and was also found guilty by a courts-martial for being absent without leave in 1863. Despite the hard service, Leep re-enlisted in January 1864.

By late 1864, Uriah Alley was determined to follow his older brother into Federal service. Despite being sixteen, on September 5 Uriah lied about his age and enlisted in 6th West Virginia in Wheeling. Young Uriah stood five feet, seven inches high, with dark hair and brown eyes. He joined Company L alongside his brother William. His term of service was one year, and he was paid a $100 bounty for enlisting. Little could Uriah have known how quickly he would experience war.

Within a matter of weeks, Uriah and William found themselves guarding New Creek (now Keyser), in the eastern panhandle of West Virginia. New Creek served as a major Federal supply depot along the vital Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, the U.S.’s major east-west artery. Due to its strategic value, New Creek was guarded by several fortifications, most notably Fort Kelley (also known as Fort Fuller). Uriah and William belonged to the 700-man garrison protecting New Creek; despite the garrison’s size, many of the men were unarmed. Only 160 toted weapons, and “they principally with arms which had been condemned.”

On November 27, 1864, Major General Benjamin F. Kelley fired a telegram to Colonel George R. Latham, commander of the New Creek garrison. “Put your post in the best possible condition for defense, as it is possible that the rebels will attack you,” Kelley warned. Shortly after midnight, Colonel Latham replied, “I am prepared for them.” Latham strengthened and extended his picket lines. Headed his way were 2,000 Confederate troopers under Major General Thomas Rosser.

Despite the Federals’ knowledge of the Rebels’ approach, the Confederate cavaliers had a ruse planned. The Confederates knew the Union garrison was expecting the return of a large cavalry patrol. Dressing dozens of men in captured Federal uniforms, an advance party of Rebels approached New Creek around 10 a.m. under the guise of the returning cavalry scouts. This ruse worked repeatedly on four picket posts, each time the Confederates riding close enough to quickly and quietly overwhelm the Union outposts. With Rosser’s main column not far behind, the entire Confederate force managed to slip through the Union picket lines and into New Creek untouched and undetected.

When the Confederates drew within thirty yards of the Federal fortifications, “at a given signal, they drew their pistols and commenced firing on my men,” Colonel Latham reported. The Rebels “set up a horrible yell and charged down with great fury upon the fort,” noted the Wheeling Intelligencer. As with the pickets, the Federal garrison initially thought the arriving soldiers were Union cavalry. Caught flatfooted, and with most of the garrison unarmed, there was little that could be done. “They got possession of the artillery, and having but 160 armed men in camp, they were almost immediately overpowered, as the whole rebel column, some 2,000 strong, dashed impetuously upon them. The panic and stampede became in a few moments hopelessly general; to rally was impossible.” Quartermaster Agent Winants similarly reported, “The surprise was complete and successful.” While Rosser’s men pilfered New Creek, a smaller detachment was sent to destroy railroad machinery and shops a few miles north at Piedmont, but they were checked by a detachment of Company A, 6th West Virginia Infantry (Uriah and William were attached to Company L, and apparently were in New Creek proper). After a three hour firefight, the Confederates burned what the could and returned to the main force.

The Confederate raid on a New Creek was a disaster for Union forces. Tens of thousands of dollars of damage was done as commissary stores, uniforms, ordinance, quartermaster wares, and buildings and 200 wagons went up in flames. The fort’s magazine was blown up, and siege guns spiked. The Rebel raiders captured four pieces of field artillery, 400-500 head of cattle and sheep, and eight stands of United States colors. For their efforts, the Confederates lost 2 killed, 2 wounded. Colonel Latham reported several men wounded, but 443 captured; General Rosser put the number of captured at 700-800 (virtually the entire garrison). General Robert E. Lee was thrilled with the raid, as the “expedition was conducted with great skill and boldness, and reflects great credit upon General Rosser and the officers and men of his command.” Despite a court-martial, George Latham survived the mishap and ended the war a brigadier general.

Uriah and William Alley were not so fortunate. They had been among the poorly armed New Creek garrison and were both captured. Union newspapers reported the mistreatment of the New Creek prisoners. “The rebels put the prisoners on the double-quick and ran them through the mud for about three miles. When any of the prisoners would attempt to avoid a miry place in the road , which they frequently did, they were rewarded for their care by a slap across the head or shoulders with a sabre.” Yet the Confederates, having imbibed freely of captured whisky from New Creek, drunkenly allowed many Union prisoners to escape. Uriah and William slipped away as night fell, hiding atop a nearby mountain. The following morning, believing the coast was clear, the two brothers descended, only to be captured yet again.

Firmly in Confederate clutches, the Alley brothers were marched to Richmond in the middle of winter. Without shoes (perhaps taken by raiders or worn out on the march), Uriah carried scars on his feet for the rest of his life from the trek. Arrival at infamous Libby Prison in Richmond offered little comfort. Uriah came down with dysentery, and William shared his ration of parched corn to keep his brother alive. The Alley boys fought off lice and struggled to keep warm.

On February 17, 1865, Uriah and William were paroled and sent to Camp Chase, Ohio. Uriah fought to regain his health, but suffered from pneumonia and “general debility” that kept him from again taking the field. He mustered out in June 1865 in Wheeling, bringing a much-needed end to his brief, luckless military career. He went home to Cameron and returned to farming.

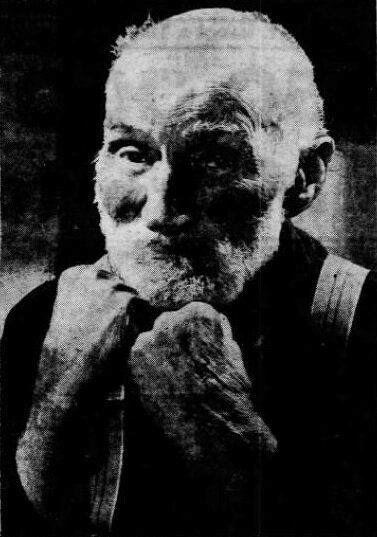

Despite his unspectacular military career, “Uncle Duck” Alley’s connection to the Civil War grew in importance as the years passed by. Living well into the 20th century, Uriah Alley became the oldest Civil War veteran living in West Virginia. His Civil War legacy brought him a degree of local notoriety, and he was interviewed by several newspapers and Life magazine.

By all accounts, Uriah’s old age did little to temper his sense of adventure. A well-known and popular figure in Cameron’s community, Alley traded horses (his great pastime) and played checkers with younger men downtown. As one Cameron local mused, “When he gets too old to trade horses he’ll not even be here.” Even into his 90s, Alley continued to enjoy life. “I still love to chew ‘Happy Jim’ (chewing tobacco),” he confessed to a newspaper reporter. “I smoke a little and I don’t mind a drink now and then.”

In February 1946, disaster struck when Alley’s home burned down in a fire. Though Uncle Duck escaped, warning two other occupants of the house in the process, the 98-year old was homeless. The Cameron community quickly rallied around Uriah Alley. A neighbor took him in, while local churches, veteran’s groups, and civic organizations pledged the funds and materials needed to build Alley a new home.

In August of 1946, Alley visited Aspinwall Veterans’ Hospital in Pittsburgh, where he met recovering World War II veterans and reflected on the care of veterans. He chatted with fellow soldiers, albeit several generations younger than he, and opined that modern hospitals were “awful nice.”

Uriah T. Alley passed away at age 99 in 1947, the last surviving Union veteran in West Virginia. He is buried in Cameron, and in 2019, a historic marker was placed in his hometown to commemorate Alley’s unique Civil War legacy in West Virginia.

A Civil War historian, Dr. Zac Cowsert holds a PhD in history from West Virginia University, where he also received his master's degree. He earned his bachelor's degree in history and political science from Centenary College of Louisiana in Shreveport. Zac’s dissertation explored the American Civil War in Indian Territory (modern Oklahoma), and his research interests include the Civil War Trans-Mississippi, Southern Unionism, and the interactions between Civil War armies and newspaper presses. ©

Sources & Further Reading:

Richmond Daily Dispatch.

Wheeling Daily Intelligencer.

Wheeling Daily Register.

Fluharty, Linda Cunningham. "6th W.Va. Infantry, Uriah Talmage Alley," WVGenWeb. https://www.wvgenweb.org/marshall/6-duck.htm

National Archives. M508. Compiled Military Service Records of Volunteer Union Soldiers Belonging to Units Organized for Service from the State of West Virginia. Accessed via Fold3.

Rada, Jr. James. "Keyser a strategic stronghold during Civil War." Cumberland Times-News. October 8, 2012. https://www.times-news.com/news/local_news/keyser-a-strategic-stronghold-during-civil-war/article_6752279c-409c-5518-8886-9a06284189e0.html

"Skirmishes at Moorefield (27th and 28th), affair at New Creek (28th), and skirmish (28th) at Piedmont, W.Va. Reports." Official Records of the War of the Rebellion. Series 1. 43:1. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=coo.31924080776929&view=1up&seq=673