Editorial: Nathan Bedford Forrest Day: A Failure of Morality, History, and Politics

/Today is Nathan Bedford Forrest Day in Tennessee.

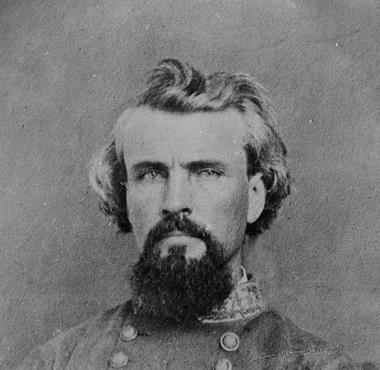

For those who don’t know, Nathan Bedford Forrest (whose middle name must always be included for some reason) was a Confederate cavalry general in the Western Theater during the Civil War. He proved an aggressive, capable commander, hailed by some as a something of a self-taught military genius. In his own apocryphal words, his strategy was simple: “Git thar fustest with the most mostest.”

Like many Southern commanders, he enjoys a prominent place in Civil War memory. And however regrettable, the celebration and veneration of Confederate commanders isn’t particularly unusual even today, circa 2019. After all, Tennessee also recognizes Robert E. Lee Day and Jefferson Davis Day.

There’s always a certain segment of the public, and definitely a certain segment of the Civil War world, willing to divorce military figures from the causes for which they fought. Great generals get pedestals and proclamations, even if their causes were atrocious and in no way reflect the values or morality of the 21st century. And any attempt to tear down those pedestals or trash those monuments is met with cries of “revisionist history” (an especially silly charge from a historian’s point of view, since history is always being revised in the face of new evidence) or “political correctness” (I find that most things labelled “politically correct”…are just correct).

Yet we cannot divorce military commanders or their abilities from the causes for which they fought, at least not when it comes to deciding who gets a pedestal and who gets a proclamation. Confederate generals chose to renounce their allegiance to the United States to join in a rebellion whose raison d’etre was slavery. They fought for an immoral, terrible cause, the world is a better place because they lost, and they are not worthy of veneration. Why are we still celebrating them?

But to be fair, Nathan Bedford Forrest isn’t just any Confederate commander. Let’s not deny Nathan his favorite hits. Born into poverty, Forrest sought to improve his material standing in a variety of ways, but nothing proved more lucrative than slave trading. In the 1850s, he moved to Memphis to expand his slaving business. He bought a prime piece of real-estate on Adams Street downtown and built an empire on the backs of human beings.

One of those humans was Horatio Eden, sold in Forrest’s Memphis slave yard: “We were all kept in these rooms but when an auction was held or buyers came, we were brought out and paraded two or three around a circular brick walk in the center of the stockade. The buyers would stand nearby and inspect us as we went by, stop us, and examine us.”

With a prosperous business buying and selling human lives, Forrest grew in wealth and prominence. When the Civil War broke out in 1861, he unsurprisingly joined the Confederate cause as a private. He rose quickly through the ranks, earning a reputation as an aggressive, straightforward general who excelled as a raider. He’s long been considered an exceptional commander, a “wizard of the saddle,” though more recent military scholarship has begun to challenge this narrative.

Like their commander, Forrest’s troopers were hard-bitten, hard-fighting soldiers, whose appealing grit and determination allow many today to overlook just what they were fighting for. The Fort Pillow Massacre should remind us.

On the morning of April 12, 1864, Forrest’s 1,500 men struck a small, 500-man garrison at Fort Pillow in West Tennessee. Among the United States defenders were Southern Unionists of the 13th Tennessee Cavalry and African-Americans of the 2nd and 6th United States Colored Artillery.

Attacking from all sides, the Southern troopers quickly breached the fort’s outer defenses, but for several hours struggled to crack the inner fortifications. In the afternoon, Forrest demanded the fort’s surrender, warning “Should my demand be refused, I cannot be responsible for the fate of your command.” The United States soldiers refused anyway.

The Confederates swarmed over the inner defenses in a final afternoon assault. As the Rebels overwhelmed the fort, they found themselves faced with runaway slaves and white Southerners in Federal uniforms. The enraged Confederates massacred them. As one Southern sergeant recalled, “The poor deluded negroes would run up to our men fall upon their knees and with uplifted hands scream from mercy but they were ordered to their feet and shot down. The whitte [sic] men fared but little better. Their fort turned out to be a great slaughter pen.” Before that slaughter stopped, over 276 Federal soldiers lay dead, including 64% of the fort’s African-American contingent.

In command, the responsibility for the massacre rested at Forrest’s feet, but there’s little evidence he felt any initial remorse over the incident. Instead he crowed that the affair “will demonstrate to the Northern people that negro soldiers cannot cope with Southerners.”

Nathan Bedford Forrest finished the Civil War a Confederate lieutenant general.

After war’s end, Forrest helped established the first iteration of the Ku Klux Klan, an organization dedicated to ousting Republican rule and returning Democrats—and white supremacy—to power. Forrest served as the KKK’s “Grand Wizard” until 1869. He ultimately left the organization and ordered its dissolution, which of course didn’t happen, and the KKK instead embraced increasingly violent, terrorist tactics to accomplish its racist aims.

Late in his life, his views on race apparently softened, as he disavowed racial violence and the Klan.

This is the man Tennessee is honoring today. What exactly merits an official day of remembrance? Forrest’s inhumane entrepreneurship? The massacre of black and white United States soldiers? His role in founding the KKK? If we’re supposed to find a redemption story in his less-racist views later in life, I don’t…nor would it redeem a lifetime of inhumanity and violence. All of this history deserves to be explored and remembered; none of it should be honored by the State of Tennessee with a proclamation.

But a proclamation Forrest got, and Tennessee Governor Bill Lee signed the proclamation on Wednesday this week. Of course, by Thursday the proclamation was rightfully under fire. Democrats and Republicans alike have denounced the proclamation. When asked about his decision to sign the proclamation, Lee responded, “I signed the bill because the law requires that I do that and I haven’t looked at changing that law.”

Bill’s not wrong. Tennessee Title Code 15 (Holidays), Section 15-2-101 states the following:

Each year it is the duty of the governor of this state to proclaim the following as days of special observance: January 19, “Robert E. Lee Day”; February 12, “Abraham Lincoln Day”; March 15, “Andrew Jackson Day”; June 3, “Memorial Day” or “Confederate Decoration Day”; July 13, “Nathan Bedford Forrest Day”; and November 11, “Veterans' Day.” The governor shall invite the people of this state to observe the days in schools, churches, and other suitable places with appropriate ceremonies expressive of the public sentiment befitting the anniversary of such dates. [Consider this post my expressive sentiment befitting the anniversary of such this date.]

So honoring Forrest, Lee, and the Confederacy is firmly ingrained in Tennessee legislation. Not only has Governor Lee not bothered to consider changing this law, he also declined to offer an opinion on whether it should be changed. (And to be fair, prior governors have followed the law as well, apparently blind to its idiocy.)

I don’t know about you, but I really appreciate the crassness of a politician who pretends to be ignorant of history, ignorant of the law, ignorant of the political climate, and ignorant of the current (much deserved) reappraisal of Confederate history.

Let’s get to the point. Nathan Bedford Forrest was not a force for good. He made money by selling human beings, earned a general’s stars fighting for the right to own human beings, and founded a post-war organization dedicated to reducing the rights of other human beings. To be crass myself, Forrest was an asshole.

In playing possum on this issue, Governor Bill Lee either doesn’t understand history, doesn’t have the courage to acknowledge history, or is playing gross politics. Maybe he’s never bothered to brush up on Forrest. Maybe he doesn’t understand that the Confederacy stood for slavery. Maybe he doesn’t understand the pain and fear and shame that many Americans undoubtedly feel when his state decides to honor a man who so fiercely fought for white supremacy.

But he damn well should. He should know the history of his state. He should know the link between Forrest and slavery and massacre. He should know the link between the Confederacy and slavery. He should know the laws of his state. He should have an opinion on those laws. He should know how to change those laws. These things are literally incumbent to his job.

And if, as I suspect, Bill Lee’s refusal to acknowledge the problems with the proclamation represent his pathetic attempt to avoid offending the “Lost Cause” views of certain red-blooded Tennesseans, he’s abdicating moral responsibility and historical literacy in hopes of saving a few votes. And to a certain extent, that’s exactly what happens when Americans prioritize military skill and bravery over morality and history.

Down with the Nathan Bedford Forrest Days, and Robert E. Lee High Schools, and Jefferson Davis Highways of the world. If history matters, we should look it in the face, acknowledge these men for what they were, and agree that their accomplishments on behalf of such a wretched cause are not worthy of commemoration in today’s world.

Zac Cowsert currently studies 19th-century U.S. history as a doctoral candidate at West Virginia University, where he also received his master's degree. He earned his bachelor's degree in history and political science at Centenary College of Louisiana, a small liberal-arts college in Shreveport. Zac's research focuses on the involvement and experiences of the Five Tribes of Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) during the American Civil War. Zac has published in the Chronicles of Oklahoma, North Louisiana History, and Hallowed Ground (magazine of the American Battlefield Trust). He has also worked for the National Park Service at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park. ©

Sources & Further Reading:

Allison, Natalie. “Gov. Bill Lee signs Nathan Bedford Forrest Day proclamation, is not considering law change.” The Tennessean. July 12, 2019.

Cimprich, John. Fort Pillow, A Civil War Massacre, and Public Memory. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2005.

Cowsert, Zachery. “The South Needs to Commemorate Its Southern Unionists.” Civil Discourse. August 25, 2017.

Hickox, Will. “Remember Fort Pillow!” Disunion, blog of the New York Times. April 14, 2014.

Huebner, Timothy S. “Confronting the true history of Forrest the slave trader.” Memphis Commercial Appeal. December 8, 2017.

Hurst, Jack. Nathan Bedford Forrest: A Biography. New York: A.A. Knopf, 1993.

Powell, David A. Failure in the Saddle: Nathan Bedford Forrest, Joseph Wheeler, and the Confederate Cavalry in the Chickamauga Campaign. New York: Savas Beatie, 2010.

Tures, John A. “General Nathan Bedford Forrest Versus the Ku Klux Klan.” Huffpost. July 6, 2016.

Ward, Andrew. River Run Red: The Fort Pillow Massacre in the Civil War. New York: Viking, 2005.

Waters, David. “New historical marker to tell truth of Nathan Bedford Forrest, slave trade in Memphis.” Memphis Commerical Appeal. March 5, 2018.

Wills, Brian S. “Nathan Bedford Forrest.” Tennessee Encyclopedia.

*Special shout-out to Will Hickox’s superb Disunion piece on Fort Pillow and Timonty Huebner’s piece in the Commercial Appeal, from which I pulled the Horatio Eden and Fort Pillow quotes.