Flying Dutchmen: The XI Corps at Chancellorsville

/I say dam the DUTCH. Gen. Hooker soon ordered the 12th corps to kill every man that run in the 11th. I saw a number of Officers and privates shot trying to break thriugh the guard. It served them right. A coward will soon play out here. We had one in our Battery. The Capt soon ordered charges made out against him. I hope they will shoot him. If I ever run I am willing to have them shoot me.

~Darwin D. Cody of Battery I, 1st Ohio Artillery writing his parents on May 9, 1863 from Brooks Station

On the evening of May 2, 1863 Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson marched his Confederate troops to the edge of the woods near the Chancellor crossroads in northern Virginia. Ahead of them lay the campfires of the Union XI Corps, seemingly unsuspecting of what was about to occur. At 5:15, Jackson glanced at his watch and motioned his troops forward. As his mile-wide battleline swept through the first regiments of the XI Corps, Union soldiers caught unawares panicked and fled frantically to the rear. A few regiments down the line, Union soldiers turned to meet the onslaught and tried to put up a resistance, but it was too late. The Confederate momentum continued, pushing the Union line back one mile and shattering the Union XI Corps. Only the wounding of Jackson himself stopped the Confederate momentum, even though darkness had already fallen over the battlefield.

In the aftermath of defeat at Chancellorsville, the XI Corps received the bulk of the blame. They had run, had crumbled under Jackson’s attack without resistance. They were labeled cowards and forevermore known as the “Flying Dutchmen.” The nickname was earned within a short period of time on the battlefield but the series of events that caused the XI Corps’ flight was put into action long before that moment, even before the armies knew they would meet in the Wilderness west of Fredericksburg.

By the end of 1862, the XI Corps were veterans of John C. Fremont’s Western Virginia expedition, and the Second Battle of Manassas, but they were brand new to the Army of the Potomac. Having been added to the army after the bloody disaster of Fredericksburg the rest of the army did not welcome or necessarily trust the newcomers who had not yet proven themselves within the Army of the Potomac. To make matters worse, the XI Corps was deemed “foreign” due to a large percentage of German soldiers. Thus the seeds of distrust toward the XI Corps were sown early.

Trouble first arrived on the wave of reforms and changes Hooker brought about when he took command of the Army of the Potomac in January 1863. He reorganized the army back into a system of corps and dismantled Ambrose Burnside’s Grand Divisions. Unhappy with the change was General Franz Sigel who was left in the command of his old corps—the XI Corps was the smallest corps in the army. He was the most senior of the major generals in the army and felt entitled to command a larger corps. When he was not given a new command, Siegel left. The natural successor to his post would have been Carl Schurz, the most senior divisional commander and a well known member of the German community. Instead, Hooker gave command of the XI Corps to Oliver Otis Howard to settle feathers ruffled when he promoted Daniel Sickles to corps command before Howard. Howard was the total opposite of the German troops now under his command, and had trouble connecting with them and gaining their loyalty. The general commanding under Howard, Charles Devens, took his position the week before the campaign and also replaced a popular officer, Nathaniel McLean, reducing McLean to brigade command. Devens was a harsh disciplinarian with a dislike from non-New Englanders. This leadership was not what the men wanted or needed, and they lost their fighting spirit with the absence of Siegel and other familiar officers.

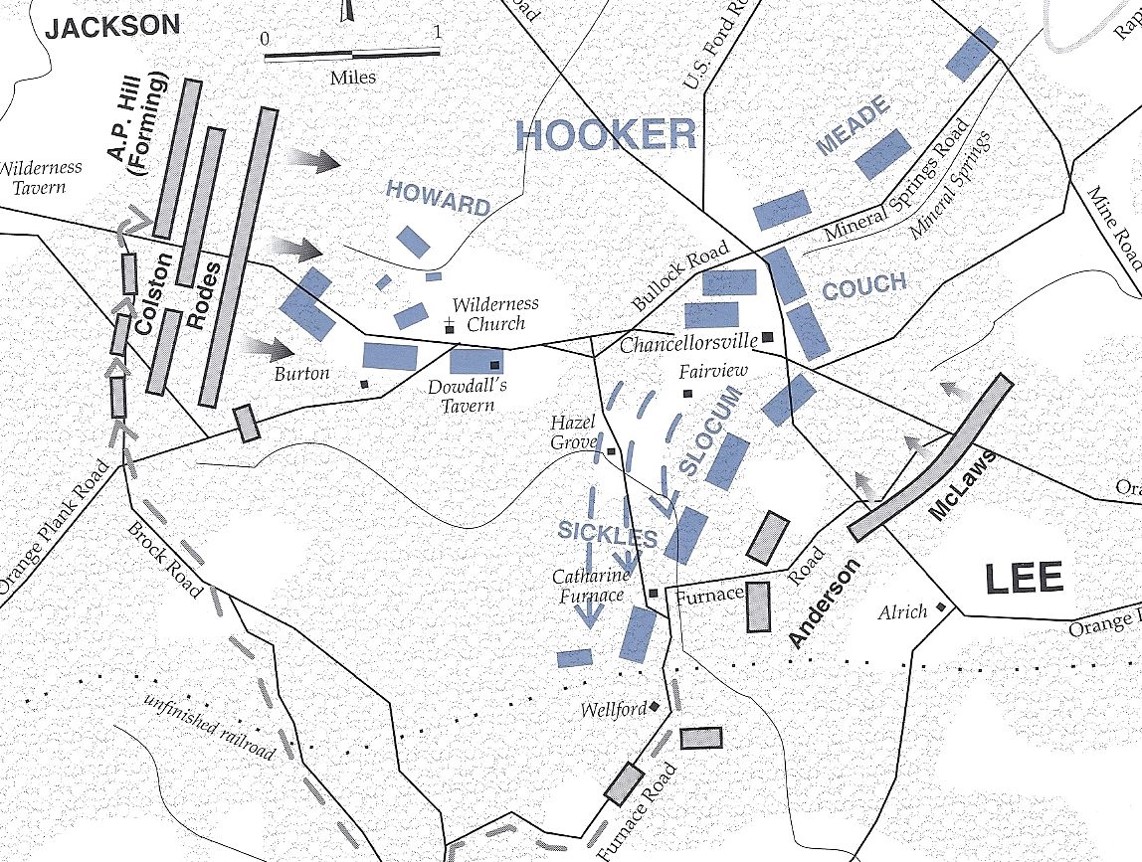

On the march to Chancellorsville, the XI Corps led the flanking column to the fords, but then followed the corps of Meade and Slocum to cross the river and take up their position. As the campaign developed, Hooker placed the XI Corps—his smallest and least trusted corps—on the Union right, far away from any probable fighting. The XI Corps line stretched along the Orange Turnpike facing south. The right flank was protected by only two artillery pieces and two infantry regiments refused back from the main line.

On May 2, Hooker watched through gaps in the trees a large body of Confederate troops marching southwest, away from the main action at Chancellorsville. It looked like Lee was retreating from the field, but he knew it could be something very different. At 9:30 AM he sent a dispatch to Howard and Slocum:

I am directed by the major general commanding to say the disposition you have made of your corps has been with a view to a front attack by the enemy. If he should throw himself upon your flank, he wishes you to examine the ground, and determine upon the position you will take in that event, in order that you may be prepared for him in whatever direction he advances. He suggests that you have heavy reserves well in hand to meet this contingency.

J.H. Van Alen

Brig. General and A.D.C.

We have good reason to suppose that the enemy is moving to our right. Please advance your pickets for purposes of observation as far as may be safe in order to obtain timely information of their approach.

General Howard did nothing to follow this directive.

Wanting to ascertain the Confederate intention, Hooker granted Daniel Sickles’ request to take his III Corps down to engage the column. The III Corps engaged the Confederate rearguard around Catherine’s Furnace. But while the rearguard put up a fight, the rest of the column did not engage but continued marching to the southwest. After his skirmish Sickles reported his successful movement and that they had poured cannon fire into the “retreating column of the enemy.” The perceived unwillingness of the Confederate force to deploy and engage in battle as well as their course in a direction away from the battle, convinced Hooker that Lee was in fact retreating. At 2:30 Hooker sent a circular to all of his corps commanders: “The Major General commanding desires that you replenish your supplies of forage, provisions and ammunition to ready to start at an early hour tomorrow.” If Lee was going to retreat into Virginia, Hooker was ready to push his advantage.

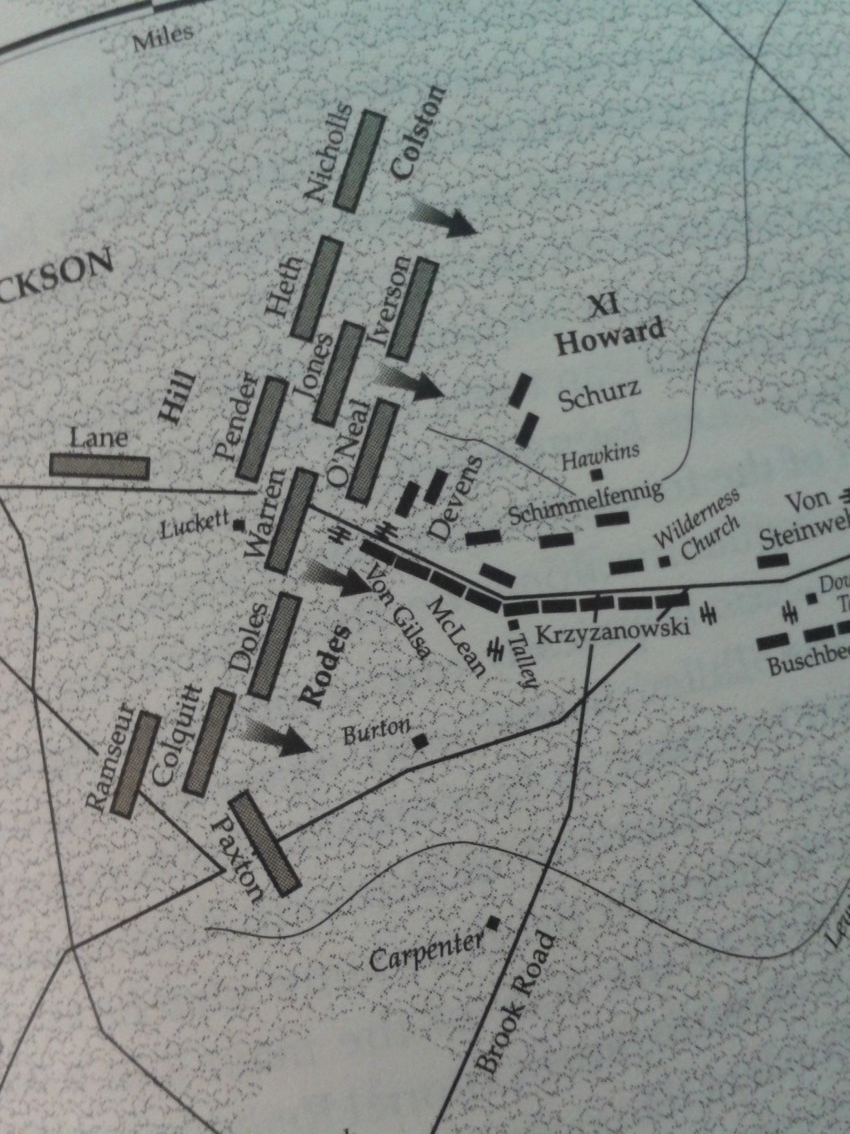

Meanwhile, once past the III Corps skirmish at Catherine’s Furnace, Jackson and his men angled back to the northwest and headed towards the Orange Turnpike. At some point that afternoon, members of the XI Corps began to see signs of Confederate movement in front of them. There is a debate over what XI Corps soldiers were reacting to, whether Jackson’s column or the presence of regular Confederate pickets; it is possible that hindsight and humiliation led soldiers to report the presence of Jackson’s column earlier than possible. Either way, several XI Corps soldiers report in their memoirs that they reported Jackson’s column to corps headquarters only to be turned away. Colonel John C. Lee of the 55th Ohio claimed that he reported sightings by his pickets to General Devens three times and was turned away each time as simply frightened. Colonel Charles W. Friend of the 75th Ohio claimed that he was laughed away from headquarters, and Colonel William P. Richardson (25th Ohio) and Colonel William H. Noble (17th Connecticut) shared similar experiences.

Finally Major General Carl Schurz rode to XI Corps headquarters to report his own sighting of increased Confederate activity to their front. He urged General Howard to change the orientation of his line to face west, but was ignored. Howard and Devens believed that military information should come from the top, not the bottom, so they believed Hooker’s assertion that Lee’s army was retreating. Any contrary reports from the XI Corps were just the results of easily frightened and unreliable German soldiers. Instead of addressing the concerns of his subordinate officers, Howard sent his only reserve (Barlow’s Brigade) to support Sickles and both Howard and division commander Brigadier General Adolph von Steinwehr rode with them to see the “main show” of the battle.

On his own, Schurz dropped three regiments behind the main line and turned them to face west near Dowdall’s Tavern. He ordered Brigadier General Alexander von Schimmelfennig to run patrols down the plank road but the resulting reports of Confederate activity were laughed at and ignored at headquarters. On the far right, Colonel Leopold von Gilsa bent two of his regiments to face west and placed two cannons at the angle also facing west. Captain Owen Rice of one of these two regiments, the 153rd PA, led pickets out to silence Confederate sniping and reportedly ran into a body of Confederate infantry. He sent a message back to von Gilsa: “A large body of the enemy is massing in my front. For God’s sake make dispositions to receive him!” Von Gilsa reported to headquarters with this message and was told that no force could possibly get through the tangled Wilderness. Hubert Dilger, known as Leatherbreeches for his choice in pants, was in command of the 1st Ohio Light Artillery stationed on the Plank Road and rode out himself. When he encountered Jackson’s force he bypassed corps headquarters and reported it straight to Hooker’s headquarters; he was turned away. Hooker’s attention was preoccupied with supporting Sickles’ push on Lee’s “retreating” army. The seemingly weak and unreliable XI Corps was right where Hooker wanted them, well behind the battlelines and out of the fight.

As the afternoon progressed into early evening, the XI Corps settled down to follow Hooker’s orders. They slaughtered cattle, cooked rations, and prepared to move in the morning. As the men relaxed, ate, and played music a deer bounded through camp causing laughter and cheers among the men. But this deer was followed by more animals—deer, a flock of turkeys, and rabbits—and suspicious commotion in the woods surrounding the Union line. This wave of animals was the precursor to a wave of grey, Confederate men rushing upon the unprepared Union soldiers. Jackson’s mile long battleline hit the Union line squarely on its flank, quickly collapsing the Union position and wrapping around it on both sides. Von Gilsa’s men were overrun quickly, some regiments holding for a few minutes, others fleeing without firing a shot. The fleeing soldiers and the pursuing Confederates hit the next troops in the line, those of McLean. McClean’s men held for longer, but were soon swept aside. Colonel John C. Lee galloped to the Corps Headquarters, but General Devens denied this report as he had the others and refused to send support. Those in the line who tried to realign themselves to face the Confederate onslaught were battered apart by friend and foe alike. Hubert Dilger’s artillery stood its ground for as long as it could, then slowly retreated down the plank road by firing and letting the recoil of the gun move the gun toward safety. Dilger was awarded the Medal of Honor for this action during the battle.

“In 15 minutes we were all cut to pieces. There was no place left us but to flee for our lives which we did with a right good grace.”

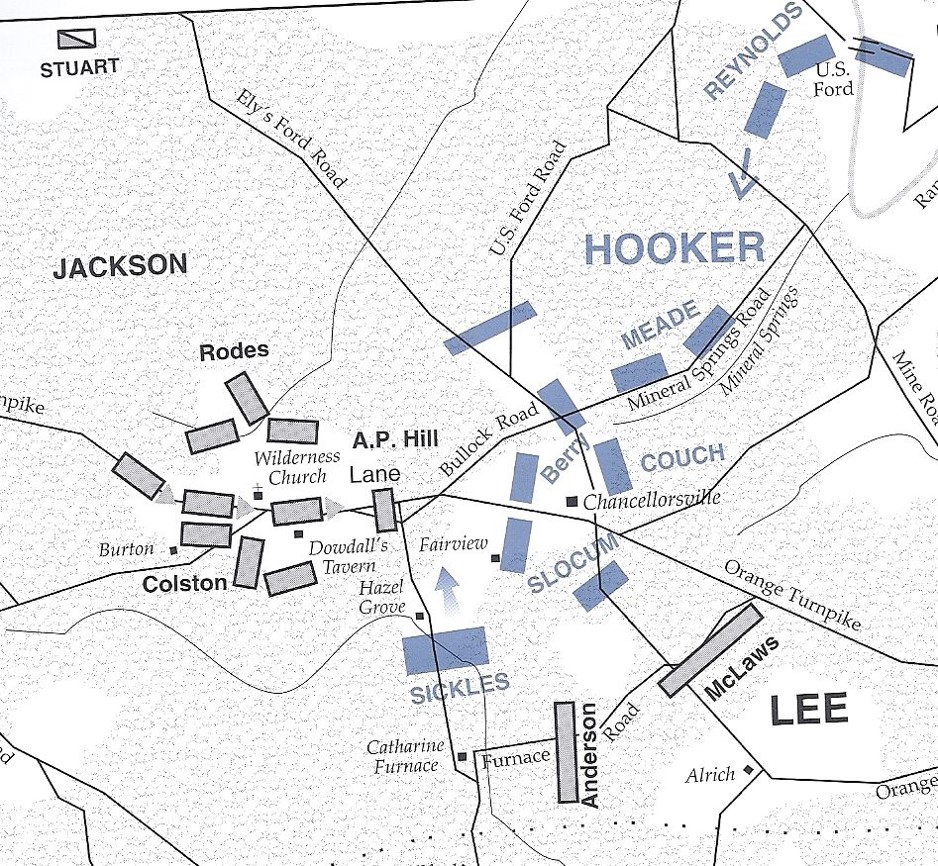

~Thomas Evans

The XI Corps made its last stand near Dowdall’s Tavern in the shallow rifle pits dug by the three regiments Schurz had turned back earlier that afternoon. This line of four thousand men, under the command of Adolphus Buschbeck, withstood four separate advances by Jackson’s roughly 20,000 man force before giving way to the larger Confederate force. Schurz tried to rally his men into a charge against the Confederates but after three or four failed tries, he gave up. The Confederates finally swarmed their lines and the final remnants of the XI Corps retreated towards Chancellorsville. While they could not stop the grey tide entirely, they bought precious time for the broken XI Corps to retreat to safety and for the rest of the Union army to react.

Once the fleeing men reached corps headquarters, General Devens finally reacted and tried to rally the men. That effort was abruptly halted when Devens was wounded in the foot. With his entire corps in chaos, Howard returned to the scene and tried to stop the stampede. He tucked a United States flag under the stump of his amputated arm and rode into the fray shouting at his men. In that moment, Howard remembered, “I felt…that I wanted to die. It was the only time I ever weakened that way in my life, before or since, but that night I did all in my power to remedy the mistake, and I sought death everywhere I could find an excuse to go on the field.” One Ohio captain remembered Howard as cool and collected, urging his men to reform and slow down, making sure he was the last man off the field. On the contrary, Union soldier Jim Peabody reported that he heard Howard yelling among the fleeing men: “Halt! Halt! I’m ruined, I’m ruined! I’ll shoot if you don’t stop. I’m ruined, I’m ruined!” When Howard saw the Confederates coming, Peabody says he saw Howard leave for the rear and commented: “I thought he was going there to impart the same information to them he had given us; that is, ‘I’m ruined.’ None of us knew or cared where he went.”

A natural acoustic shadow prevented Hooker from hearing the chaos on their far right until the fleeing mob was upon them. The General and his staff fell among the men, hitting them with the flat edge of their swords, but could not stop the momentum. Some of the XI Corps men ran so far in their haste that they ran into the Confederate force on the other end of the Union line.

Hooker frantically pulled Sickles men and their supports up from Catherine’s Furnace to stop Jackson, but the Confederate attack began to slow down naturally. It was getting dark on the field now as evening deepened and the Confederate line was in such a state of disorganization that officers had to stop their lines and regain control of their men. The attack was called off completely after Jackson was wounded later that night. At the end of the day, Jackson’s attack had completely crushed the right wing of Hooker’s army back over a mile and they stood posed to push their success farther. May 3rd sealed Confederate victory as the Confederates continued their forward momentum and pushed Hooker off the field.

Of the 11,000 men on the XI Corps line, 2400 were casualties (22%) with 1000 prisoners taken and 9 guns lost. But the worse casualty for the XI Corps was its reputation. Coming out of the confusion of three days of fighting, the only thing the army could agree on was that the XI Corps had fled. Their retreat was an easy event for the army to hold on to as an explanation for their defeat, and the XI Corps became the scapegoat for the Union’s failure. This idea became public perception when newspapers adopted it and emphasized the XI Corps retreat in their accounts of the battle. Everyone in the XI Corps waited for General Hooker to issue his official report to set the record straight. Schurz wrote his own report to address the blame placed upon his corps, but was denied permission to publish it until Hooker’s report was out. Hooker, however, never issued an official report of the battle and his 67 page testimony to the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War explained why everyone else besides himself was to blame for Union defeat at Chancellorsville.

The charges leveled against the XI Corps from Chancellorsville were never officially refuted, and within the anti-immigrant atmosphere of mid-nineteenth century America the German soldiers proved to be an acceptable scapegoat for the army’s defeat. Their retreat on the first day of the Battle of Gettysburg did nothing to help their image. From May 2, 1863 to today, the XI Corps have been branded as the Flying Dutchmen, the Cowards of Chancellorsville. Do they really deserve that name? Consider Hubert Dilger, awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions along the Plank Road, holding off the Confederates and saving as many of his artillery pieces as he could. After the war, he never spoke of his honor because it was too shameful to admit he was part of the cursed XI Corps. Several factors combined on May 2 to create the situation in which the XI Corps fled; mistrust between XI Corps leadership and their men, mistrust of the XI Corps by the rest of the army, the failure of corps command to fully investigate reports of Confederate activity, and Hooker’s focused belief that Lee was retreating and his failure to be prepared for the possibility of a flank attack meant that the soldiers left on the Union far right were unprepared for the attack that hit them. In the large picture, yes, the XI Corps broke and fled. But was it their innate cowardice and ineffectiveness as soldiers that caused the retreat, or were their superiors to blame for creating a situation that they could not possibly prevail in? If you were sitting down to your dinner and 20,000 men ran out of the woods at you, what would you have done? Consider that past the first few regiments who were so startled and quickly overrun that they had to flee without fighting, most other regiments attempted to form resistance against Jackson’s men, with varying degrees of success. Large elements of the XI Corps held their ground until they had no choice but to flee or die. Placed in an untenable position, with little or no preparation, and faced with a numerically superior force emboldened by surprise and momentum, it is highly unlikely that any force could have held in that situation. Perhaps now, more than 150 years after these actions, we can vindicate the XI Corps and place the blame upon those who truly deserve it.

Dr. Kathleen Logothetis Thompson graduated with her Ph.D. from West Virginia University in 2017. She earned her M.A. from West Virginia University in 2012 and her B.A. in history with a Certificate in Revolutionary Era Studies from Siena College in 2010. In addition, Kathleen was a seasonal interpreter at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park from 2010-2014 and has worked on various other publications and projects.