Secrets of a Cemetery, Part VII: Beyond the Civil War

/Read the rest of the series here.

The National Cemetery at Fredericksburg contains more than just Civil War burials. Yes, the vast majority of soldiers buried there fought between 1861 and 1865, but veterans of the Spanish-American War, World War I, and World War II are also buried within the cemetery.

For example, while we have several women buried in the cemetery next to their veteran husbands, we have two women buried there on their own right. Edith Rose Tench claims the distinction of being the first woman buried in the National Cemetery. She served during WWI as a yeomanette, third class in the United States Naval Reserve Force at the Norfolk Navy Yards. 11,000 Yeomanettes served during the war performing tasks such as clerical duties, designing camouflage for battleships, and acting as translators, draftsmen, fingerprint experts, and recruiting agents. After the war Tench graduated from Mary Washington Hospital in the class of 1928, but died November 20, 1929 after a long illness with Bright’s Disease. A second woman buried in the cemetery also served in WWI. Annie Florance Lockhart (grave #6715) served as a US Army Corps Nurse first at Camp Meade, MD and then on the Meuse-Argonne front in France. She came to Fredericksburg in 1931 and was the superintendent of Mary Washington Hospital for three years before her 1935 death from pneumonia.

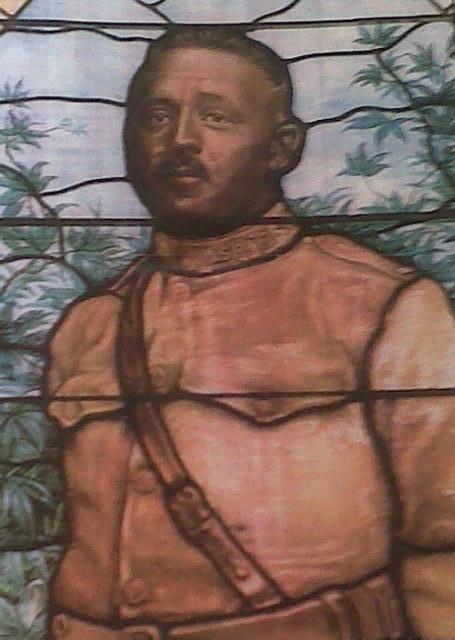

Another first is represented by the side-by-side burials of Urbane Bass and his wife Maude. Urbane was Fredericksburg’s first African-American physician. He moved from Richmond in 1909 and established a medical practice and pharmacy on William Street that mostly served black customers due to segregation. When the United States entered WWI, Bass offered his services as a physician for the Army Medical Corps. He was in France by early 1918, serving as lieutenant in the 372 US 93 Div. On October 17, 1918 he was attending to wounded soldiers on the field when he was hit with shrapnel from a nearby explosion. Both legs were severed and he died before he could be taken from the field. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his actions and reburied in the Fredericksburg National Cemetery on July 23, 1921, the first burial of a black commissioned officer in the cemetery. His 32 year old widow, Maude, remained in Fredericksburg with their four children until 1922. She then moved to Raleigh, NC where she raised her family and taught music to the blind for thirty years at the North Carolina State School for the Blind. Maude lived until the age of 100, never remarried, and is buried beside her husband in the “Officer’s Row” near the entrance of the cemetery.

The only known set of brothers interred in the cemetery are veterans of the Spanish-American War. Twenty-seven year old Leighton G. Forsythe (grave #6632) and his younger brother Jesse (grave #6633) both served as privates in the 4th US Volunteer Infantry; Jesse enlisted under the name Charles Dunn, likely so the brothers could remain together in the face of military policy that forbade brothers from serving in the same regiment. Both brothers died on August 7, 1898 when they were struck by a train on the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad near Potomac Run, about six miles north of Fredericksburg. The reason they were on the tracks is unclear, they may have been walking toward Brooke, VA to catch a train to Washington, DC where their unit was camped.

Two father-son pairs represent the two world wars. Amdol L. Jett served as private first class, Co.K, 318 Inf. 80 Div, US Marine Corps in WWI. He was discharged from service June 3, 1919 and lived until November 26, 1940 when he died at the age of 51. Less than five years later, his son, Amdol Glorial Jett, died while serving as a US Marine during WWII. Jett deliberately exposed himself at Iwo Jima to draw enemy fire in order to locate enemy gun positions. The directions he called back enabled Marine gunners to score a direct hit on an enemy position. His efforts cost the 22 year old his life, and his mother and two sisters lost son and brother so soon after losing husband and father. Both father and son are buried together in grave #6742 in the National Cemetery.

Jack Butler and his son, Roy Gordon Butler, also share a grave in a sense. Jack immigrated to America in 1907 but returned to England in 1915 to serve in the 2nd Squadron of the Royal Flying Corps in WWI. He was wounded in August 1916 when his plane was shot down during a raid on German lines. During his convalescence he married Doris Tucker and the family returned to America in the 1920s after Jack was honorably discharged. Jack opened a garage in Fredericksburg, but he died at an early age from appendicitis. At the time of his death, approval of his application for US citizenship was expected, which probably explains why he was buried in the National Cemetery. Jack’s son, Roy, served as a corporal in the US Air Force during WWII; when he died on November 2, 1986 his family scattered his ashes over his father’s grave.

Kathleen Logothetis Thompson graduated from Siena College in May 2010 with a B.A. in History and a Certificate in Revolutionary Era Studies. She earned her M.A. in History from West Virginia University in May 2012. Her thesis “A Question of Life or Death: Suicide and Survival in the Union Army” examines wartime suicide among Union soldiers, its causes, and the reasons that army saw a relatively low suicide rate. She is currently pursuing her PhD at West Virginia University with research on mental trauma in the Civil War. In addition, Kathleen was a seasonal interpreter at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park from 2010-2014 and has worked on various other publications and projects.