"A Very Spicy Little Sheet": The Knapsack, A Soldiers' Newspaper and the Politics of War

/This post is the latest in Zac Cowsert’s series “The Civil War in the Press,” which explores the interactions between soldiers and civilians, politics and the press throughout the Civil War. You can read other posts in the series here.

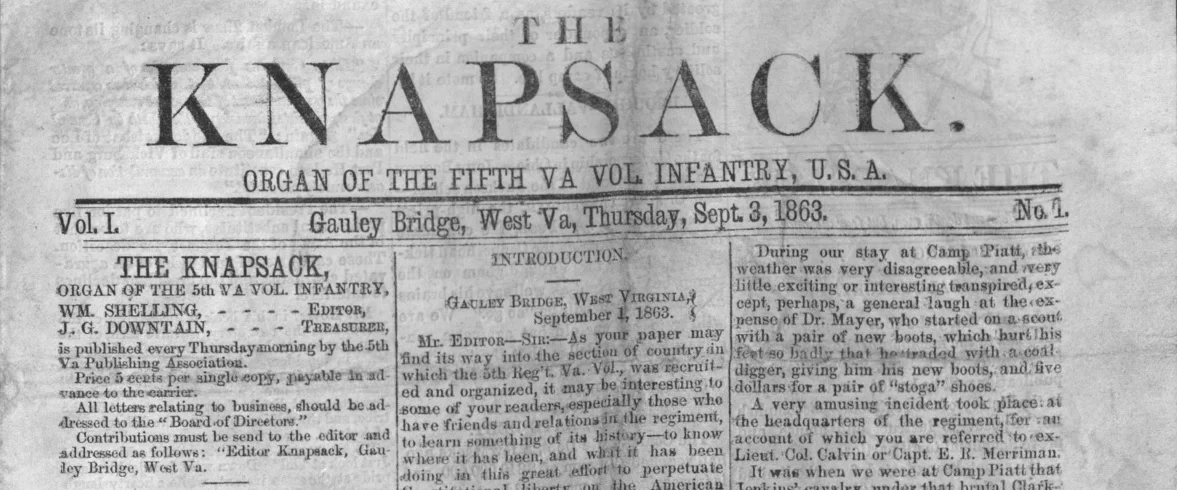

A Union officer once remarked, “Does not a newspaper follow a Yankee march everywhere?” In the fall of 1863, the soldiers of the Fifth West Virginia Infantry found themselves stationed at Gauley Bridge in the southern part of their newly-minted home state. It proved to be a relatively peaceful posting and, apparently true to Yankee form, the men promptly set about establishing a regimental newspaper. Forming the rather grandly named Fifth Virginia Publishing Association, the Association soon began issuing copies of the four-page Knapsack every Thursday morning at five cents a copy. Although only published for a few months, the paper illuminates much about soldier life and the politics of war.

In the Knapsack’s salutatory message, the paper’s first editor William Shelling made clear its goals. Hoping to cater to the “military, moral and intellectual interests of the regiment,” the Knapsack offered a wide variety of information meant to inform, entertain, and uplift its readers. Equally important, however, was to document the Fifth West Virginia’s service throughout the war. As the paper proclaimed, “when we shall have returned to our homes, to our families and friends; we can turn over its leaves and read, with pleasure and happy recollections, to an eager listening circle of contented and joyous faces, the history of our regiment.” Accordingly, from the first September issue onward, the paper published a continuing history of the Fifth’s experiences in the war thus far.

The Knapsack’s pages provide a window into daily soldier life. The paper published the schedule of religious services, praised the temperance of the soldiers in camp, lamented their prolific profanity, shared the excitement of a well-organized deer hunt, and happily announced the creation of a soldier-run bakery in camp—“an important progress, which will be valued highly by the ‘Boys’.” When a favorite dog of the Fifth’s wagon drivers went missing, “a great sensation was produced in the social circle of the wagoners’ mess,” resulting in the poetic eulogy “The Lost ‘Dorg’” in The Knapsack’s pages. The regimental surgeon Daniel Meyer reminded readers of the importance of sleep, and the necessity of cooking beans fully before consuming them (otherwise “a person might almost as well swallow…leaden bullets”).

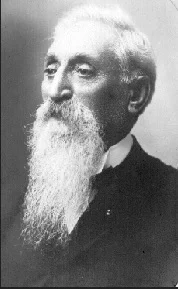

The paper also kept its readers abreast of military affairs on other fronts, ranging from depredations by Rebel guerrillas in Missouri to the Union’s bombardment of Charleston, South Carolina. The Knapsack also tracked the constant campaigning in Virginia between Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia and George Meade’s Army of the Potomac. The soldiers of the Fifth likely monitored the unfolding events in Virginia with considerable interest. The year prior, they had fought against both Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson and Robert E. Lee in the Shenandoah Valley and Second Manassas campaigns respectively. Only in late 1862 had the regiment returned to West Virginia, and the new year of 1863 also ushered in a new brigade commander for the 5th West Virginia: colonel and future president Rutherford B. Hayes. Although Colonel Hayes confided to relatives that his new command had “some of the best, and I suspect some of about the poorest troops in service,” he seems to have thought well of the Fifth. Hayes noted the regiment had “behaved well” in the campaigns of 1862 and added of their colonel, Abia Tomlinson: “Their present commander is an excellent man and I look for good things from them.”

While military affairs were clearly important, nothing captured the attention of the Knapsack’s authors more than the upcoming Ohio gubernatorial election. Two men—Clement Vallandigham and John Brough—sought to occupy the governor’s seat in Columbus, and the difference between the two couldn’t have been more striking. Clement Vallandigham belonged to the anti-war faction of the Democratic Party, often termed “Peace Democrats” or “Copperheads,” and fervently believed that only by laying down its arms could the North hope to be reunited with the Southern states. In May of 1863, his opposition to the Northern war effort led to his arrest for “publically expressing…sympathy for those in army against the Government of the United States, and declaring disloyal sentiments and opinion, with the object and purpose of weakening the power of the Government in its efforts to suppress an unlawful rebellion.” Vallandigham’s arrest sparked a national furor and was widely seen as unlawful. Abraham Lincoln, hoping to defuse the situation, banished Vallandigham to the Confederacy, who in turn had no use for the Ohioan. Vallandigham sought refuge in Canada, where he remained until 1864. Despite his Canadian exile, he was nominated by Ohio Democrats as their gubernatorial candidate in June, and throughout the fall Peace Democrats stumped across the state on his behalf. The Peace Democrats railed against abolition and emancipation, conscription, Vallandigham’s arrest, enlistment of African-American troops, rising debt, and perceived assaults on civil liberties by the Lincoln administration. Above all else, they called for an end to the war. In sharp contrast, War Democrats and Republicans countered Vallandigham’s nomination by rallying behind John Brough, a War Democrat himself who proclaimed that “slavery must be torn out root and branch” and vowed “to aid…in sustaining the Government in the great work of suppressing this most wicked rebellion, and restoring our country to its former unity and glory.”

Thus the 1863 Ohio gubernatorial election was a referendum on the war itself: Vallandigham for immediate peace or Brough for continued prosecution of the war. Unsurprisingly, soldiers on the front lines took immense interest in the election. Despite its designation as a West Virginia regiment, many soldiers of the Fifth West Virginia actually hailed from Ohio and were registered to vote there. The writers for the Knapsack knew as much and decisively staked out their claim for “a vigorous prosecution of the war” and support for “the present administration in all its efforts to crush the rebellion and restore the Union of the States.” The Knapsack denounced Copperheads as traitors, who “insult soldiers, spit upon them (when they dare), call them hirelings, slaves, abolitionists, and fighters for the negroes.” The paper’s editors wondered whether “any soldier be so dead to all sentiment of manhood as to vote with such a party?” The Knapsack fully endorsed John Brough and hoped “the vote will be so unanimous and decided that the traitors and sympathisers [sic] everywhere will understand that soldiers do not fight their enemies with guns and at the same time fight their friends with the ballot.” William Shelling, the Knapsack’s first editor, didn’t think Vallandigham would get half a dozen votes from the soldiers at Gauley Bridge.

By all accounts, the authors of the Knapsack got their wish. On October 15, the election results finally reached the soldiers in West Virginia. Just before midnight, Lieutenant William McKinley woke his good friend Colonel Rutherford B. Hayes with the good news. Hayes’ brigade—including the Fifth West Virginia—had voted unanimously for John Brough. Indeed, out of the 44,000 Union soldiers who had cast votes in the Ohio election, 94% of them (41,000) had voted for Brough, who swept the home vote as well. Hayes elatedly wrote in his diary “A victory equal to a triumph of arms in an important battle.” To his mother he wrote, “Our soldiers rejoice over the result of the Ohio election as much or more than the good people at home.” The two future presidents—McKinley and Rutherford—celebrated Brough’s victory by distributing whiskey to the men. Lincoln too celebrated the important victory in Ohio by exclaiming, “Glory to God in the highest, Ohio has saved the nation!”

Undoubtedly both the Knapsack and its readers in the Fifth celebrated Brough’s victory as well. Unfortunately, we don’t have the details of their celebration since only two extant issues of The Knapsack survive, the last dated October 8, 1863. It is possible further issues were published, but by December, 1863 the regiment was campaigning again and may have needed to cease publication.

Despite its short tenure, the Knapsack managed to gain hundreds of readers (based on subscriptions), enjoyed the support of the regiment’s officers and men, and made an impression throughout the region. The Wheeling [WV] Daily Intelligencer praised it as a “very spicy little sheet,” and the Pomeroy Telegraph [OH] thought it “a real source of improvement to the regiment” and wished it “abundant success.” More importantly, however, the Knapsack provides a unique window into soldier life in camp and the politics of the Civil War, both in the North and among soldiers on the front lines. The Knapsack reveals how Union soldiers consistently found ways to entertain and inform themselves during the war and, even after experiencing combat, continued to believe in the cause for which they fought.

Zac Cowsert currently studies 19th-century U.S. history as a doctoral student at West Virginia University, where he also received his master's degree. He earned his bachelor's degree in history and political science at Centenary College of Louisiana, a small liberal-arts college in Shreveport. Zac's research focuses on the involvement and experiences of the Five Tribes of Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) during the American Civil War. He has worked for the National Park Service at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park. ©

Further Reading and Sources:

Primary Sources:

The Knapsack (Gauley Bridge, WV). The West Virginia and Regional History Center in Morgantown, WV holds a copy of Vol. 1, No. 6 (Oct. 8, 1863) of the Knapsack. Both the Library of Virginia and Duke University each hold copies of Vol. 1, No. 1 (Sept. 3, 1863).

Wheeling Daily Intelligencer (Wheeling, WV).

Hayes, Rutherford B. Diary and Letters of Rutherford Birchard Hayes, Nineteenth President of the United States. Vol. 2. Charles Richard Williams, ed. Columbus: Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society , 1922.

Trial of Hon. Clement L. Vallandigham by a Military Commission. Cincinnati: Rickey and Carroll, 1863.

The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Robert Scott et. al., eds. Vol. 29, Part 2. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1890.

Secondary Sources:

Abbott, Richard H. Ohio's War Governors. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1962.

Armstrong, William Howard. Major McKinley: William McKinley and the Civil War. Kent, OH: Kent University Press, 2000.

Klement, Frank L. Copperheads in the Middle West. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1960.

Lang, Theodore F. Loyal West Virginia from 1861 to 1865. Baltimore: Deutsch Publishing Co., 1895.

Rawley, James A. The Politics of Union: Northern Politics during the Civil War. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1974.

Reid, Whitelaw. Ohio in the War: Her Statesmen, Her Generals, and Soldiers. Vol. 1. Cincinnati: Moore, Wilstach, and Baldwin, 1868.

Weber, Jennifer L. Copperheads: The Rise and Fall of Lincoln's Opponents in the North. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.