Prisoners Among the Pines: Texas' Camp Ford

/During the Civil War, hundreds of thousands of young men found themselves prisoners of war, their fates in the hands of the enemy. For those lucky enough, parole or exchange awaited. Yet most men faced the grim reality of harsh prison camps. Some Civil War prisons were so infamous their names are still notorious today: places like Andersonville, Elmira, Libby Prison, and Point Lookout. Yet perhaps their names overshadow the fact that over 150 prison camps existed during the war.

Tucked away among the piney woods of East Texas rests a small historic park in Tyler, Texas. The park's humble appearance today belies the magnitude of the place it commemorates. Camp Ford constituted the largest Confederate-run prisoner-of-war camp west of the Mississippi River, housing some 5,550 Union soldiers over the course of the war's final years.

Initially designed as a training camp for local troops in early 1862, Camp Ford was named after John S. “Rip” Ford, a Texas Ranger of Indian-fighting fame. A Confederate colonel, Ford spent the war in the Rio Grande Valley, earning a footnote in history for his fruitless victory at Palmetto Ranch in May, 1865. Although initially useful, Camp Ford eventually fell into disuse and some disrepair.

The events of 1863, however, brought Camp Ford back to the fore. Federal activity in neighboring Louisiana increased, and Confederate authorities in need of prisoner-of-war camp selected Camp Ford for the purpose. Although not ideal as a prison site (the camp had no walls), the small number of prisoners proved manageable to the Rebel guards. So much so, inf fact, that prisoners were allowed to go into town under guard. The camp was managed by a West Pointer, Colonel R.T.P. Allen, and garrisoned over time by local militia, the 15th Texas Cavalry, and Texas Reserve and Home Guard units variously.

During the fall of 1863, the situation at Camp Ford began to change. Dozens of prisoners morphed into hundreds, and the facility was overwhelmed. The vulnerability of the camp was not lost on outsiders either. Three local Unionists plotted to help prisoners escape, and although their conspiracy was uncovered, the incident sparked fear in the local populace. Utilizing the slaves of local planters, Confederate authorities constructed a 16-ft. high stockade, enclosing the camp’s approximately three acres and several hundred prisoners and easing the situation.

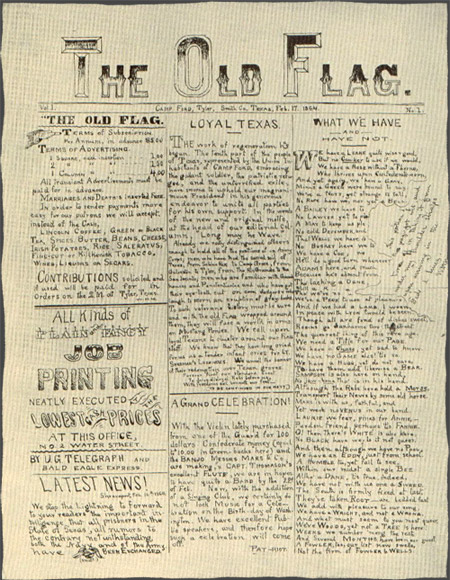

For the Federal prisoners at Camp Ford, prison life proved boring. Finding ways to while the time, men occupied their hours by carving wood and playing baseball. Captain William May of the 23rd Connecticut used a bit of ingenuity and managed to produce several issues of a camp newspaper, The Old Flag. As Lt. Colonel Duganne, a prisoner of Camp Ford, remarked, “Does not a newspaper follow a Yankee march everywhere? So, of course, Camp Ford possessed its journal; though we boasted neither types nor printing-press; so, notably, we discussed our prison-affairs in editorial columns, and trumpeted the merits of our small wares in flaming advertisements.”

Prisoners worked to improve their surroundings, building cabins and naming the camp’s various “streets”. An imprisoned Navy captain was named Camp Ford’s “Commissioner of Aqueducts.” Though the title may have been facetious, the job’s duties were not. Camp Ford had its own natural spring, and the Commissioner helped ensure that separate facilities were built for bathing, cleaning and drinking the spring’s water. The availability of fresh water and its sanitary use helped contribute to the camp’s incredibly low mortality rate. Indeed, only 6%, or approximately 330 of the 5,500 prisoners who passed through Camp Ford died there. In comparison, Andersonville claimed 29% of its inhabitants, and Elmira claimed 25%.

The situation deteriorated in the spring and summer of 1864. In the spring, the Confederate army under General Richard Taylor (son of U.S. President Zachary Taylor) earned resounding victories at Mansfield and Pleasant Hill just south of Shreveport, Louisiana. Fought barely 100 miles from Tyler, the thousands of prisoners captured in these engagements were sent to Camp Ford. The three-acre camp was overwhelmed, and and the stockades were cut in half to provide lumber necessary to build new walls, increasing the camp’s size to eleven acres. The cabins of 1863 were a dream now, as soldiers scrapped dugouts (termed “shebangs”) into the hillsides to give themselves a semblance of shelter. Rations were inadequate, often for guard and prisoner alike. Tools were scarce and construction slow; shipments of tools and clothes from the U.S. government did slowly help ease the miserable situation. Eventual prisoner exchanges also helped reduce overcrowding and improve camp conditions.

Camp Ford held a variety of different prisoners throughout this time, Union soldiers and sailors hailing from dozens of states. The camp held more naval personnel than any other prison camp during the war, North or South; many of the naval personnel came from U.S. riverine squadrons serving along the Mississippi and Red Rivers. Included in this contingent were at least 27 black naval personnel, who were apparently used for labor around the camp by Confederate forces.

The collapse of the Confederate in early 1865 brought relief for the prisoners of Camp Ford. On May 19, 1865, the approximately 1,800 U.S. prisoners were paroled and set free. Two months later, a detail of the 10th Illinois Cavalry destroyed Camp Ford. Today, the grounds of the camp are preserved and well interpreted, largely due to the efforts of the local Smith County Historical Society. Camp Ford reminds us of the war's tremendous cost and reach; hundreds of thousands of men wasted away months and years in prisoner camps all across America. The experiences of these men and the sites of their imprisonment, big and small, deserve recognition and remembrance.

Zac Cowsert currently studies 19th-century U.S. history as a doctoral student at West Virginia University, where he also received his master's degree. He earned his bachelor's degree in history and political science at Centenary College of Louisiana, a small liberal-arts college in Shreveport. Zac's research focuses on the involvement and experiences of the Five Tribes of Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) during the American Civil War. He has worked for the National Park Service at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park. ©

Further Reading & Sources

Camp Ford. Texas State Historical Association.

Flavion, Gary. "Civil War Prison Camps." Civil War Trust.

Life in a Texas Prison Pen: The 48th Ohio at Camp Ford. This website contains large excerpts from Lt. Colonel Duganne’s Camps and Prisons: Twenty Months in the Department of the Gulf, which paint an excellent account of life at Camp Ford.

Mitchell, Jr., Leon. "Camp Ford, Confederate Military Prison," Southwestern Historical Quarterly 66 (June, 1962): 1-16.

A Short History of Camp Ford. Smith County Historical Society