A Challenge Issued: The Hartwood Church Raid

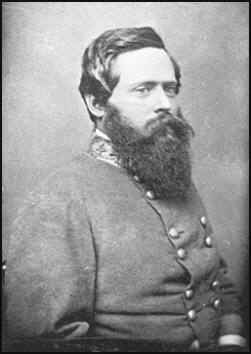

/Four hundred cavalrymen splashed across the icy waters of the Rappahannock River in central Virginia, moving north into enemy territory. The Confederate cavaliers, undeterred by the bitter cold and snowfall nearly eighteen inches deep, consisted of some of the Old Dominion’s finest: portions of the First, Second and Third Virginia Cavalry. At the gray-clad column’s head was twenty-eight year-old Fitzhugh Lee, nephew to Robert E. Lee and already a grim veteran of war’s horrors. On this day, February 24, 1863, Brigadier General Fitz Lee led his men across the Rappahannock in reconnaissance, seeking to determine what movements, if any, the Union Army of the Potomac was undertaking around Fredericksburg. The mission’s directive had come from Robert E. Lee himself.

The Rebel troopers, as yet unopposed by Federal cavalry, bedded down for the night some “20 miles from camp,” reported Adjutant Tayloe of the 2nd Virginia Cavalry. “We…cleared away the snow, laid down some fence rails and some pine tops on top of them, built large fires and spent a comfortable night,” Tayloe noted. Warmly fortified throughout the night, the Confederates got an early start the next morning, the 25th. Pushing deeper into Union territory, the Southerners finally approached the Union picket line near Hartwood Church. A stately red brick building, only built in 1858, Hartwood was home to a devout Presbyterian congregation. On this cold February day, however, three Union vedettes (mounted sentries) of the 16th Pennsylvania Cavalry had sought shelter near the church. Lieutenant-Colonel Edward S. Jones of the 3rd Pennsylvania, writing after the fact, penned an account of what happened next:

A corporal in charge of one of the picket reserves came in and reported that he had (being posted so that the picket at the church could be seen) observed how the enemy captured our three vedettes at Hartwood Chuch. Three of the enemy rode up [to the Union vedettes], having on our regular army overcoats, and when halted he [the Union sentry] let them advance without dismounting. In a moment our pickets were made to dismount and marched off….The column of the enemy immediately appeared, and the corporal hasten to report to our headquarters.

The apparent bit of Rebel trickery worked, and the Confederate force had created a crucial gap in the Union picket screen. Slipping through it, they proceeded to wreak havoc upon nearby Federal forces.

Union Lieut.-Col. Edward Jones, who had yet to learn the how the Southern soldiers penetrated the picket line, had finished breakfast when reports of fighting came into headquarters. Riding out in the direction of Hartwood Church, he encountered an officer of the 16th Pennsylvania “shouting that the rebels were charging down the road. A bend [in the road] prevented me from seeing any grand distance, and in almost a moment a squad, filling the road and charging at full speed, commenced firing at me.” Jones turned his horse, Old Ironsides, around and made a quick escape through a nearby swamp.

Fitzhugh Lee’s men pushed past Hartwood Church, sweeping all before them. Lee reported that his command “routed them, and pursued them within 5 miles of Falmouth.” Still, as Lee’s raiders charged onward, resistance began to mount. Squads of the 3rd Pennsylvania counter-charged the enemy and attempted to quell his advance. Adjutant Tayloe’s account of the affair testifies that within “15 minutes we saw the Yankees swarming out of a piece of woods and forming line of battle.” Undaunted, the 1st Virginia Cavalry charged, “driving the Yankees before them like sheep.” The Confederate regiments hammered the Union horsemen. As a Northern witness mused, “considering the [poor] conditions of the roads, [the Federals] made very good time to the rear.”

The advance halted only as the Confederate troopers neared infantry lines. Charles Weygant of the 124th New York Infantry, the “Orange Blossoms,” witnessed the approach of the routed Federal cavalry. “A small squadron of cavalry passed out by us on a dead run. Presently the came dashing back, through a piece of woods just in front of us, in utter confusion. Several horses were riderless, and most of the riders hatless.” Attempts to stop the cavalry’s retreat came to naught. “The officers were waving their swords over their heads, vain endeavoring to rally their men.” Weygant was not impressed with the actions of his mounted comrades. “Our frightened cavalry, as an excuse for their disgraceful stampede” he scorned, “had reported a force of the enemy’s at least three thousand strong, in the act of swooping down on our picket line. The truth probably was that a strong reconnoitering party, having come across our small body of horse, made a dash at them and accidentally ran into our infantry picket line.”

Taking charge of the regiment, Weygant ordered more infantrymen forward to support the infantry’s picket line, who began to open fire on the Confederates. “The rebels,” Weygant surmised, “evidently did not expect to meet any considerable force of infantry…and dashed off as wildly as our cavalry had come in.” Writing home about the affair some time later, Henry M. Howell of the 124th New York confided to his cousin Helen that “The regt had a lively time out on picket.” Perhaps embellishing the tale, Henry offered a more illustrious account of the affair. The 124th’s commander, seeing the Rebels coming, shouted “‘now boys remember who you are and where you come from.’” His men responded with three cheers, which “seemed to frighten the Rebs for they did not come any closer.”

On the Confederate side, Adjutant Tayloe was aware of the sudden appearance of enemy infantry “who poured a volley into us.” Although the Federal infantry ended the Confederate advance, Fitz Lee recognized that the raid’s objective had been accomplished. He had identified the location of the Federal infantry, confirming that the Federals were still ensconced in their positions about Fredericksburg. With his mission accomplished, Lee ordered a withdrawal.

Federal troopers pursued the fleeing Rebels and, in Taylor’s recollections, “came up to charge us and capture the whole concern.” Unwilling to allow the Union troopers to chastise his retreat, Lee ordered the 3rd Virginia Cavalry to charge. Lieutenant Colonel William Carter of the 3rd Virginia, a lawyer turned soldier, recounted the moment quite clearly:

General Lee ordered me to charge them with a yell, which the regiment did in most gallant style, striking at the column advancing along the road…The enemy continued to move on until we came within thirty yards of them when they broke, and fled in perfect confusion. We pursued them for a quarter of a mile, killing and capturing several of them…Retiring from this position and coming within speaking distance of General Lee, he highly complimented the regiment for the gallant charge it had made, which praise the men received with loud cheers.

Having dealt the Union cavalry a punishing blow, Fitzhugh Lee and his troopers finally “withdrew without further molestation” to the previous night’s camp and finally back to safety among the Southern lines back across the Rappahannock. It was a successful mission. Fitzhugh Lee reported only fourteen casualties, and had approximately 150 Union prisoners and considerable “plunder” to boot. Beyond this, however, Fitzhugh Lee successfully ascertained the Union positions around Fredericksburg, embarrassing the Federal cavalry all the while. J.E.B. Stuart praised Fitz Lee’s “ability and gallantry” and noted the “extraordinary obstacles and difficulties in the way of success—a swollen river, snow, mud, rain, and impracticable roads, together with distance.”

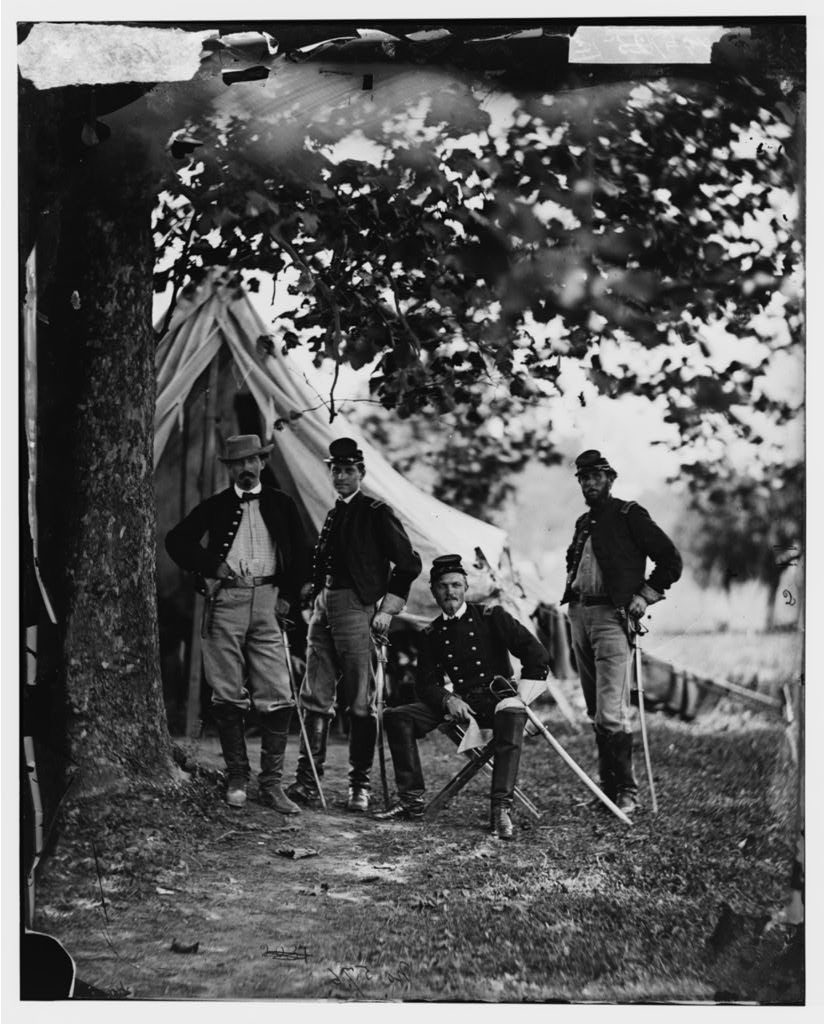

For the Federals, the Hartwood Church affair was an embarrassing disaster, albeit a small one. For one, the Federals suffered 150 men taken prisoner, along with thirty-six casualties. Moreover, the Union pickets around the church had inexplicably let their guard down to disastrous consequences, as noted by Lieut. Colonel Jones. Jones charged that “the fault and blunder lay in the neglect of duty of the pickets at the church not dismounting every one who approached, and their capture open out our whole line, to be swept off in detail.” The pickets were not the only ones who failed to act, however. Union cavalry commands, under both William Woods Averell (whose previous exploits have been explored) and Alfred Pleasonton, had failed to capture the elusive Fitz Lee on his return to Rebel lines. Although an admittedly difficult task considering the small size and speed of Lee’s force, there existed a powerful incentive. “A major-general’s commission,” Union Chief of Staff Dan Butterfield conveyed to the commanders, “is staring somebody in the face in this affair, and…the enemy should never be allowed to get away from us.” Despite the promise of promotion, the Union cavalry failed to net the fleeing foe.

General Joseph Hooker, commander of the Union army, was incensed at the whole affair. Hooker, since assuming command of the Army of the Potomac in January of 1863 following the debacle at Fredericksburg, had instituted some dramatic, positive reforms among the Union cavalry. Chief among them was his creation of a separate, independent cavalry corps, ending the Union practice of distributing cavalry regiments piecemeal to infantry commanders. Yet his reforms had failed to prevent the Hartwood Church raid. Some weeks later, Hooker would heatedly declare:

We ought to be invincible, and by God, sir, we shall be! You have got to stop these disgraceful cavalry ‘surprises.’ I’ll have no more of them. I give you full power over your officers, to arrest, cashier, shoot—whatever you will—only you must stop these surprises. And by God, sire, if you don’t do it, I give you fair notice, I will revlieve the whole of you and take command of the cavalry myself.

Although Hooker’s frustration is understandable, the simple fact that the Confederate army had to perform a reconnaissance around Hartwood to determine the Union army’s dispositions suggests that his cavalry had actually been rather successful at screening the Union army…that is, until the Hartwood raid in late February.

Yet there was the chance of Federal redemption.

Before crossing into the safety of Rebel lines, Confederate Brigadier General Fitzhugh Lee left Lieutenant Charles Palmore, a Confederate physician, among the Yankees to care for several captured wounded Confederates. Yet Palmore was hardly a harbinger of goodwill. He carried with him a note from Fitzhugh addressing his old West Point comrade and Union cavalry commander William Averell. It rudely read:

I wish you would put up your sword, leave my state and go home. You ride a good horse, I ride better. Yours can beat mine running. If you won’t go home, return my visit and bring me a sack of coffee.

Fitzhugh Lee had thrown down a challenge. The Union cavalry, embarrassed and angered by the Hartwood Church affair, would respond less than a month later, when William Woods Averell would answer Fitz Lee’s taunts at a place called Kelly's Ford...

Sources & Further Reading:

*A special thanks to historian Greg Mertz of Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park, whose knowledge of both the raid and the literature on it helped me immensely.

Carter, William R. Sabres, Saddles, and Spurs. Walbrook D. Swank, ed. Shippensburg, PA: Burd Street Press, 1998.

Driver, Robert J. and H.E. Howard. 2nd Virginia Cavalry. Lynchburg, VA: H.E. Howard, Inc., 1995.

Hubard, Jr., Robert T. The Civil War Memoirs of a Virginia Cavalryman. Thomas P. Nanzig, ed. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2007.

LaRocca, Charles J., ed. This Regiment of Heroes: A Compilation of Primary Materials Pertaining to the 124th New York State Volunteers in the American Civil War. Montgomery, NY: Charles J. LaRocca, 1991.

Nanzig, THomas P. 3rd Virginia Cavalry. Lynchburg, VA: H.W. Howard, Inc., 1989.

Regimental History Committee. History of the Third Pennsylvania Cavalry in the American Civil War, 1861-1865. Philadelphia: Franklin Printing Co., 1905.

Scott, Robert N. Official Records of the War of the Rebellion. Vol. XXV, Part I. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1889.

Starr, Stephen Z. The Union Cavalry in the Civil War. Vol. I. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1979.

Weygant, Charles H. History of the One Hundred and Twenty-Fourth Regiment, N.Y.S.V., Newburgh, NY: Journal Printing House, 1877.