Surrendering to "Genl Intoxication"

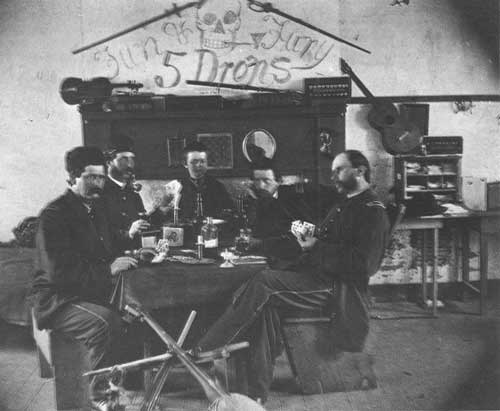

/In studying the Civil War, we often remark about the youth (sometimes the extreme youth) of the men who fought it. Yet while these men were engaged in a serious and deadly endeavor, they did not cease to be young men...capable of all the mishaps, shenanigans, and vices to which people of a young age can be suspecible. This is, of course, reflected in our own lives as well. We’ve all had our college parties or midnight soirees or one glass of wine too many. Young soldiers most certainly did, too. These are stories, both light-hearted and somber, of men surrendering to “Genl Intoxication.”

Leander Stillwell enlisted in the 61st Illinois Infantry just a few months after his 18th birthday. Having experienced the horrific shock of Shiloh, Corporal Stillwell soon found himself counting the long days during the siege of Corinth. On one such day the quartermaster of the regiment requested that two non-commissioned officers “who were strictly temperate and absolutely reliable.” Their mission: to retrieve whisky for rationing to the men. Corporal Stillwell and his friend Corporal Tim Gates, a man “somewhat addicted to stuttering when he became nervous or excited,” were selected. Our two comrades, thus armed with a large kettle full of potent liquor, began their sojourn back towards camp. It wasn’t long before the two men found themselves passing through a secluded wagon camp. Leander Stillwell recalls how things went awry:

Here Tim stopped, looked carefully around to see if the coast was clear, and then said, “Sti-Sti-Stillwell, l-l-less t-t-take a swig!” “All right,” I responded. Thereupon Tim poised his camp-kettle on a wagon hub, inclined the brim to his lips, and took a most copious draught, and I followed suit. We then started on, and it was lucky, for me at any rate, that we didn’t have far to go.

Stillwell soon found himself drunk, as the whisky coursed “through my veins like electricity.” It didn’t take long for the young man to recognize his predicament. “Its effects were felt almost instantly,” Stillwell recounts, “and by the time we reached camp, and had delivered the whisky, I was feeling a good deal like a wild Indian on the war path. I wanted to yell, get my musket and shoot, especially at something that would when hit jingle…But it suddenly occurred to me that I as drunk, and liable to forever disgrace myself, and everybody at home, too.”

Stillwell, through his drunken haze, had sense enough to slip out of camp into the woods. As he headed out, he passed a tent containing Corporal Tim Gates—his partner in crime! Tim, inebriated himself, “had thrown his cap and jacket on the ground, rolled up his sleeves, and was furiously challenging another fellow to then and there settle an old-time grudge by the ‘ordeal of battle’.” Stillwell didn’t see how his comrade fared, however, and slept in the woods, waking up hours later with a “splitting headache.”

Leander Stillwell and Tim Gates never told anyone about their little alcohol adventure, although they laughed about it from time to time. Leander Stillwell went on to become a district judge in Kansas.

Although Corporal Stillwell managed to keep his experience with drink hidden and discreet, others were not so careful. John William De Forest, a captain of Company I in the 12th Connecticut Infantry, was dismayed when his first sergeant, a grizzled German veteran, stumbled into his tent one June night with a drunken grievance to air. “Captain, I am virst sergeant of I Gumapnee,” Sergeant Weber drunkenly announced. “But, Captain, if the virst sergeant of I Gumpanee cannot be respected, den, Captain, I will resign with your bermission, and be a brivate your gumpanee, Captain.”

Sergeant Weber felt insulted when the cook had refused to give him his supper. Except that Sergeant Weber had in fact already eaten supper, fallen asleep drunk, then awoke to demand his supper…again. Captain De Forest sent the stumbling sergeant back to his tent, allowing the incident to slide. Unfortunately, however, Weber was caught drunk again in town soon afterwards and was court-martialed. Captain De Forest bemoaned the whole incident, losing his best veteran sergeant. “If we had lost two or three generals,” De Forest admitted, “I should not feel so badly.” De Forest reported later on that Sergeant Weber (likely Charles D. G. Webber of the 12th Connecticut) had his court-martial sentence reduced. Records indicate that he was reduced to the ranks in June, 1862, then promoted to corporal in January, 1863…only to be reduced to the ranks again in September of that same year.

Darker moments also arose from drinking. Sergeant Cyrus Boyd, of the 15th Iowa Infantry, scribbled down his perspective on one incident in January, 1863, while his regiment was posted in Memphis:

Whiskey O Whiskey! Drunk men staggered on all the streets. In every store. The saloons were full of drunk men. The men who had fought their way form Donelson to Corinth and who had met no enemy able to whip them now surrendered to Genl Intoxication. Some were on the side walks and both hands full of brick bats and swearing that the side walks were made for soldiers and not for any d—d ni--ers.

Inappropriate drinking, especially by officers, could also threaten the lives of both the commander and his men. In 1862, some 6,000 Federal soldiers march south out of Kansas to liberate Indian Territory (modern Oklahoma) from Confederate control. Leading the expedition was Colonel William Weer, a Kansan Jayhawker and known drunkard. Despite campaigning in the field, Weer did not abstain from his alcoholic habits. In early July, Union soldiers clashed with Confederates several times in Cherokee Nation. Yet on July 4th, celebrations went ahead undeterred. Col. Ohioan cavalrymen Luman Tenney wrote in his diary that "Col. Weir [sic], our commander, was so intoxicated that he could neither receive the report of battle or give any orders." Tenney grumbled, "So many drunk. Officers gave the freest license to the men. Both caroused. I was most disgusted." Weer's alcoholism (and general incompetence) made the Federal expedition a short-lived affair; in mid-July Weer was arrested by his second-in-command, and the Union troops returned to Kansas.

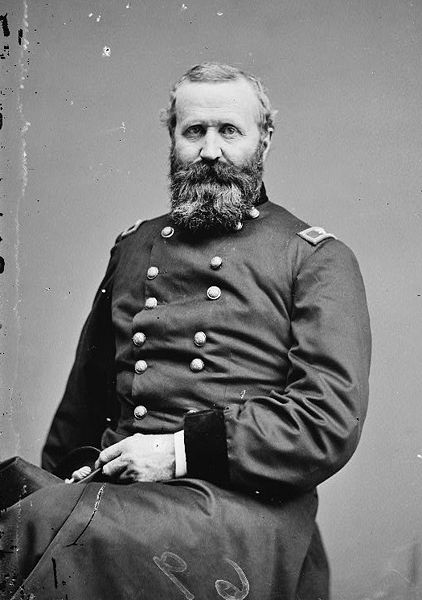

In 1864 in the Eastern theater of the war, men similarly gossiped about Union Brigadier General Alexander Hays. During the fight at Morton’s Ford in central Virginia during the Mine Run campaign in early 1864, General Hays was conspicuous on the field. He made a sport of “hooting, yelling, and riding right in the rebs faces,” only to begin “laughing to see the boys get into the mud up to their knees.” Soldiers doubted his sobriety.

Several months later, Hays and his men found themselves in a desperate fight in the untamed thickets of the Wilderness. Riding to the head of his old regiment, Hays began to address them. Tipping his canteen towards his mouth, he leaned into the path of a bullet and was killed instantly. The canteen, it was rumored, was full of whiskey.

Alcohol, then, shaped much of the men’s monotonous camp life. Most every Union soldier experienced or witnessed the effects of alcohol–both hilarious and deadly. As esteemed historian Bell Wiley tells us, drinking was more common in Northern armies simply because they had great access to liquor. It went by a dozen names: “Nockum stiff” and “tanglefoot”, “oil of gladness” and “Oh, be joyful.” Beer, brandy, gin, but especially whiskey could generally be found somewhere in the army camp. Quality rarely mattered. On soldier hazarded a guess as to the ingredients of commissary whiskey: “bark juice, tar-water, turpentine, brown sugar, lamp-oil and alcohol.” But still, Leander Stillwell and others took their chances with the stuff.

We have all probably surrendered to “Genl Intoxication” ourselves, and those same types of indiscretions were made one hundred-fifty years ago, albeit with the possibility of far more serious consequences. Just like us, those soldiers were human beings, young men full of life and vigor and a sense of invincibility. Alcohol could shape these soldiers' wartime experiences, both on and off the battlefield.

Zac Cowsert currently studies 19th-century U.S. history as a doctoral student at West Virginia University, where he also received his master's degree. He earned his bachelor's degree in history and political science at Centenary College of Louisiana, a small liberal-arts college in Shreveport. Zac's research focuses on the involvement and experiences of the Five Tribes of Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) during the American Civil War. He has worked for the National Park Service at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park. ©

Further Reading and Sources:

Confer, Clarissa. The Cherokee Nation in the Civil War. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2012.

Cowsert, Zachery. "Confederate Borderland, Indian Homeland: Slavery, Sovereignty, and Suffering in Indian Territory." MA Thesis, West Virginia University. 2014.

De Forest, John William. A Volunteer's Adventures: A Union Captain's Record of the Civil War. James H. Croushore, ed. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1996.

Rhea, Gordon. The Battle of the Wilderness, May 5-6, 1864. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2004.

Stillwell, Leander. The Story of a Common Solder of Army Life in the Civil War, 1861-1865. Franklin Hudson Publishing Co., 1920.

Tenney, Luman Harris. War Diary of Luman Harris Tenney, 1861-1865. Cleveland, OH: Evangelical Publishing House, 1914.

Wiley, Bell Irvin. The Life of Billy Yank: The Common Soldier of the Union. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1979.