Turning the “Gate of Hell” into the “Gate of Heaven”: The Secret Andersonville Death Roll of Dorence Atwater

/Late in the war, when Clara Barton finished her work in the field, she turned her attentions to a new problem: the thousands of missing and unidentified soldiers. Under her Office of Correspondence with Friends of the Missing Men of the United States Army, Clara and her assistants received at least a hundred letters a day from families searching for missing loved ones. They drew up lists of names and circulated them through the army barracks and northern post offices with requests for information.

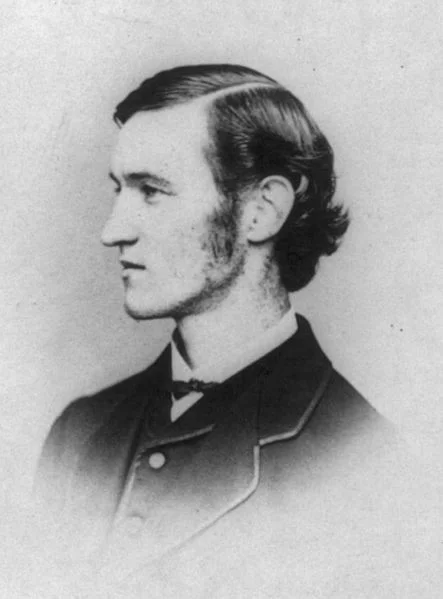

In late June, Clara received a note from one Dorence Atwater who requested a meeting with her concerning information he had about approximately 13,000 of the missing men she was looking for. Intrigued, Clara visited Atwater at his Washington hotel. Atwater had enlisted at the beginning of the war, even though he was only 16. Captured after the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863, he was first imprisoned at Belle Isle and then transferred to Andersonville when it opened in February 1864. Impressed by Atwater’s superior penmanship, the commander of Andersonville, General John H. Winder, assigned him to the surgeon’s office with orders to keep an official record of all union prisoners who died and were buried there. The Confederates promised they would turn the roll over to the Union government after the war, but Atwater suspected their sincerity as he experienced the cruelty of the prison and recorded over 100 deaths per day.

Atwater began making a second copy of the death roll when the Confederates were not looking, hiding it in the lining of his coat to keep it safe. His register included the name, unit, disease, cause and date of death, and the grave number for each soldier who died at Andersonville. When he was transferred to South Carolina and then paroled, he smuggled the death roster out with him. Here was the key to the identities of almost 13,000 missing Union soldiers.

But there was a problem.

When Atwater returned home after parole, he wrote to the Secretary of War about his death roll. Colonel Samuel Breck of the Adjutant General’s office ordered him to report to Washington, which Atwater did against the advice of family and doctors. Breck offered Atwater $300 for the roster. Atwater refused, he did not want to profit off the roles, just publish it for the benefit of the families. Breck warned him that if Atwater published it the government would declare the rolls contraband and confiscate them. Atwater then made a counteroffer: he would receive $300 and a clerkship and loan the roster to the military for them to make a copy. Then he wanted the roster back so he could properly notify the families. Breck agreed, but then delayed copying the roster because he believed Atwater’s goal was to publish the roster for profit.

This is where matters stood when Atwater saw Clara’s list and plea for help. He hoped she could help him get the roster back from the military and use it to mark the graves and notify the families. As he hoped, Clara used her connections and secured approval from Secretary of War Stanton to form an expedition, including herself and Atwater, in order to travel to Andersonville and establish a national cemetery there. The military detachment did not like having Clara and Dorence along, but the result was worth the trouble. Between July and August 1865, the expedition used Atwater’s secret rolls and the corresponding numbered sticks to letter and place white headstones with each man’s name, rank, unit, and death date at 12,461 graves. An additional 451 “unknown” headstones were placed at graves not noted on the death roster.

Clara was displeased and upset at her treatment at the hands of the military expedition, but her mission was accomplished. She wrote her impressions about Andersonville in a later memoir:

I have looked over its 25 acres of pitiless stockade, its burrows in the earth, its stinted stream, its turfless hillsides, shadeless in summer and shelterless in winter—its walls and tunnels and caves—its 7 forts of death—its ball and chains—its stocks for torture—its kennels for blood-hounds—its sentry boxes and its deadline—and my heart sickened and stood still—my brain whirled—and the light of my eyes went out. And I said, ‘Surely this was not the gate of hell, but hell itself.’ And for comfort I turned away to the acres of crowded graves and I said, here at last was rest, and this to them was the gate of heaven.”

In one effort Atwater had helped Clara identify over 12,000 missing men. But his contribution would go unrecognized. When the group returned to Washington, Colonel Breck demanded that Atwater give back the $300 or return the death rolls. Atwater refused, he had held up his end of the bargain. Breck promptly arrested Atwater for larceny (for stealing his own death roll) and confined him to Old Capitol prison. Ironically, Atwater was imprisoned in the same prison as Henry Wirz who was on trial for the horrific circumstances and casualty rates of Andersonville. Wirz was convicted of murder and conspiring with other prison officials to injure and kill prisoners against the rules of war and hanged on November 10, 1865. Wirz was one of two men tried, convicted, and executed for war crimes during the Civil War. Atwater wrote about the irony in a letter that appeared in the New York Citizen:

I am confined here in the same prison with Capt. Henry Wirz, the Andersonville jailer. He is being tried by a Military Commission for being one of the murderers of 13,000 of our men, and I am being tried for keeping and wishing to publish the names of these same 13,000 men, that the people may know where their dead are buried and of what they died.

Atwater was conviced of theft by court martial, dishonorably discharged, fined $300, and sentenced to 18 months of hard labor in Auburn State Prison, NY. He was released in December under a general order from President Johnson pardoning all prisoners convicted by court-martial of crimes less than murder, but the dishonorable discharge was not overturned. Clara instructed Atwater to stay away from Washington and worked with him to publish the death roll before the military could publish their copy. The pair succeeded in February 1866 when the New York Tribune printed the Andersonville roll as a 74 page pamphlet, complete with a forward by Dorence and Clara’s report on the Andersonville expedition. The military protested Atwater’s publication, but the pamphlet created public outrage about how the military had treated him and Clara. The public attention ensured that Clara received government funding to continue her operation until 1868, and she hired Atwater as her assistant for a time, but Atwater never received recompense from the government.

The end of Atwater’s life was just as adventurous as the beginning. A couple years after the war he was sent as Consul at Tahiti. He fell in love with the island and the people loved him in return. He also fell in love with Princess Moetia Salmon, sister to Queen Marau, and married her in 1875. When Dorence died in San Francisco in 1910, his wife accompanied his body back to Tahiti where they were greeted by most of the island’s population. He was the first non-royal given a royal funeral and was buried under a 7000lb stone carved with “Tupuuataroa” or Wise Man as he was known in Tahiti.

Atwater kept his original death roll for many years. Unfortunately, when the 1906 earthquake struck San Francisco their home was destroyed by explosives in an attempt to turn their entire street into a firebreak. Inside the home was the original roster, now destroyed.

Further Reading:

Stephen B. Oates, Woman of Valor: Clara Barton and the Civil War. Free Press, 1995.

Kathleen Logothetis Thompson graduated from Siena College in May 2010 with a B.A. in History and a Certificate in Revolutionary Era Studies. She earned her M.A. in History from West Virginia University in May 2012. Her thesis “A Question of Life or Death: Suicide and Survival in the Union Army” examines wartime suicide among Union soldiers, its causes, and the reasons that army saw a relatively low suicide rate. She is currently pursuing her PhD at West Virginia University with research on mental trauma in the Civil War. In addition, Kathleen has been a seasonal interpreter at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park since 2010 and has worked on various other publications and projects.