Experiencing the War: The Soldier's View

/For soldiers, leaving home and entering a world far different from civilian life, change would come rapidly and without mercy. Soldiers went through a psychological evolution from civilian to volunteer to soldier as they coped with the challenges of war, each step changing them more and taking them further from their civilian lives. This process included suppressing pre-war identities and creating new ones, identities based on professionalism and a certain amount of callousness in order to survive the war. The gateway to this process was what Gerald Linderman called a “simmering down” that manifested itself in several forms. As volunteers entered into the service they discarded unnecessary equipment and non-essential items to make their gear as light as possible on the long marches. In addition, the first casualties of most regiments were from disease, a “simmering down” process that thinned out the ranks. Initially, soldiers welcomed this process for they saw it as ridding the army of the weak and the cowards: New Yorker George Newcomb noted in 1862, “Eney [sic] new Regt has to go through the culling process before it will become a good and efficient Regt.” As the process continued, however, and even the bravest men died, soldiers felt their own vulnerability.

In addition, these men faced what Eric Dean called “a destroying manner of living.” Soldiers primarily marched from place to place, sometimes ten or more miles a day, with few or no breaks, often for many days in a row. Impending battle created the necessity for forced marches, with increased length and speed and no room for exhaustion. The elements were another factor as soldiers were often exposed to the weather without enough protection while on the march or being transported, in camp, and in battle. Clothing and tents were sometimes in short supply or bad condition, and at times fires were forbidden for fear the enemy would spot them, depriving soldiers of warmth and hot food. The presence of a fire did not necessarily mean comfort, however, as evidenced by a October 1862 diary entry by Cyrus F. Boyd who complained, “Had no blankets with us and we suffered much last night in the cold rain[.] We could not sleep and had to stand up about all night around a little fire which we tried to keep alive.” Charles Wright Wills also complained of the soaking rain and the cold turning his fingers blue, but the consolation was that it stopped the chiggers from biting. Conditions in camp led to uncleanliness and insect infestations, a humiliation for men accustomed to better circumstances. In addition to the chiggers, the “ants also have an affinity for human flesh and are continually reconnoitering us,” wrote Wills, “I kill about 200,000 per day. Also, knock some 600 worms off of me . . . I pick enough etomological specimens off me every day to start a museum.” These conditions facilitated the spread and ravages of disease.

Men adapted to their changed lives at different rates, some defining themselves as soldiers quickly, others becoming frightened by the changes they saw in themselves. Men transgressed against their normal behavior and the wishes of family members as the dull experiences of camp life and long winter encampments led some to try many of the vices and entertainments they had staunchly opposed at the beginning of the war. In battle, soldiers welcomed the hardening that allowed them to withstand horrific experiences, but there came a point when they no longer seemed to care about human life. “We passed around, among the dead bodies and wounded soldiers,” said Henry C. Lyon of the 34th New York, “apparently no more affected than would we be if we saw a number of Dead Beavers.” When writing about artillery fire, O.W. Norton was glad there were no women around for “[e]very time a shell exploded they would jump and think ‘there goes death and misery to some poor fellow.’” He and his fellow soldiers no longer thought that way for “we have grown so careless and hardened that we don’t heed them.” Death was ever-present in the lives of Civil War soldiers and they became indifferent to it, sometimes to the point at which they could function normally, joke, and enjoy pranks in battle or even live among the dead on the battlefield. “The scenes of blood and strife that I have been called to pass through during the months that are passed, and my ‘baptism in blood,’” admitted infantryman Warren Freeman, “have nearly destroyed all the finer feelings of my nature.”

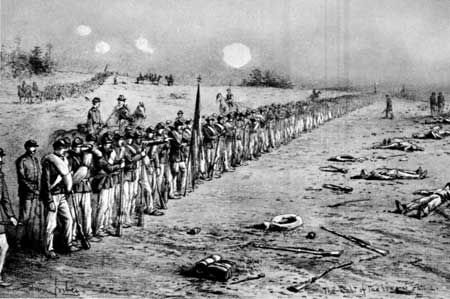

The experience of battle was a major change for most of these new soldiers. Green recruits wanted to get into the fight quickly, worried that the war would end before they saw combat. Stimulated by desires to prove their honor and manhood, new soldiers wanted to experience their first battle in order to prove themselves. Their eagerness would soon change as they experienced the worst anxiety before battle, as they moved into the vicinity of combat. Seeing the wounded streaming to the rear, the refuse of war strewn on the ground, and hearing the sounds of combat while not being personally engaged was tough on men preparing themselves for battle. “It is worse for a soldier to wait for a battle to begin than it is to do the fighting,” admitted one man. Artillery bombardments were especially intense for waiting soldiers. “Nothing is more trying to the nerves,” wrote infantryman William P. Lyon, “than . . . to have to remain silent and motionless under a fire which they are not permitted to return.” The explosion of shells was great and visible to the men, and they could not move or react in any way. An ideal expression of courage was to receive such fire without moving, but many soldiers instinctively ducked at each shell.

Once they entered into the surreal world of combat soldiers stepped into an environment of chaos and disorder. The smoke, terrain, and confusion made it difficult for them to see the enemy, or even where they were going, and, in some cases, made it difficult to maintain battle lines and command structure. Coming under fire, especially if a near-miss was experienced, could feel almost unreal. Soldiers were amazed that they could come out of such an environment unscathed, sometimes with bullets having passed so close to have left holes in clothing or equipment. Sounds assaulted their ears, the varying sounds of shot and shell and the sounds of their comrades yelling or dying. Deaths on the battlefield were shocking and disillusioning to many soldiers. Civil War era men were used to death as it occurred in the civilian world: comprehendible, neat, orderly, respectful and surrounded by ceremony and family. The deaths they now witnessed were the opposite: chaotic, random, sudden, and gruesome.

The impact of battlefield fatality could be particularly severe when soldiers witnessed the close range deaths of family members, friends, or close comrades. Austin Carr of the 82nd New York went to war with a friend from home, and their friendship continued through their military service. Fred was standing in front of Austin in battle when a bullet ripped through his side and bowels, a wound that Austin knew was fatal. Austin leaned over his friend and heard his last words, but had to leave him behind. Expressing a sense of brokenness and anguish at the thought of his friend lying ruined on the battlefield, Austin volunteered for burial duty the next morning in the hope of finding Fred’s body. Unlike so many, he was fortunate enough to locate the remains: “And then—there he was—lying so still, my buddy, Fred, He had given all that was possible for a man to give, somehow I felt bitter in my heart against this thing called war.” Fred was lucky enough to be buried by a friend in an individual grave on the side of the hill away from the others, unlike most soldiers during the war. Austin would never forget the death of his friend: “I could scarcely bring myself to look upon his crude grave,” he wrote, “tears gushed down my face in spite of all my efforts to stop them, and so I bid him goodbye and left him there to sleep. The bitter wound in my heart to last forever.”

Many soldiers reported feeling no fear in the midst of battle—the anxiety disappeared and they were able to focus on their tasks, ignoring danger, bodily needs, and the passage of time. While dreading battle as it approached, a New Hampshire private stated that “it isn’t long before you won’t think or care whether you are in it or not . . . for a man in the heat of battle thinks nor cares for nothing but to make the enemy run.” As James McPherson points out, this was probably due to a rush of adrenalin produced from the high level of stress resulting from battle. Those men who overcame the initial “flight” reaction, turned into fighting machines so committed to battle that their actions have been labeled combat frenzy, fighting madness, or battle rage. Civil War soldiers did not know about the body’s chemical reactions to stress or about adrenaline, but they did recognize when men were “fighting crazy” or performing almost inhuman feats on the battlefield. In the fighting around Petersburg, William Phillips was astonished by his response to battle: “My eyes saw it all, in red and flame, but I could not digest it somehow.” Rushing forward, led by “some other power than myself” he ran straight into the Confederate works. This “combat narcosis” definitely assisted soldiers in battle, making them almost numb to the events around them, even though they were still witnessing and experiencing them. “During that terrible 4 or 5 hours that we were there I had not a thought of fear or anything like fear,” wrote a Massachusetts lieutenant about Malvern Hill, “on the contrary I wanted to rush them hand to hand.” He had been dreading the battle the entire day before, he admitted, “yet it seemed as the moment came all fear and all excitement passed away and I cared no more than I would in a common hail storm.” Once soldiers were on the field of battle they relied on the absence of fear and the simplification of battle to a “common hail storm” to do their job.

The absence of fear in battle helped men fight, but it also heightened the reality of the aftermath when they began to inspect the battlefield. The debris of war was scattered over the ground, which itself bore the marks of battle, but the worst sight was the dead and wounded men. There was no time to give each casualty the attention usually given to the dead in civilian life; instead, remains were buried hastily, sometimes in mass graves, or neglected completely. Remains left uncovered for days before burial crews could reach them were almost unrecognizable as men; soldiers detailed to burial duty had to deal with these scenes in addition to the experience of battle. Men described being unnerved and sickened by the sights seen after battle, wishing they would never have to see them again. Some retained mental images of certain deaths that they could not forget. The trauma of these experiences came at a vulnerable time for soldiers, when they were feeling the physical and psychological collapse after the rush of battle. A man’s supply of adrenalin is not unlimited; the end of a battle, or even a lull or retreat in the midst of battle, could cause severe reactions as the body tried to restore its chemical balance. The physical and mental impact of what they had just done finally set in; they realized how tired, dirty, sore, and thirsty they were and could feel depression, low morale, and sudden vulnerability. Surveying the damage and feeling physically affected by battle, the fears men had pushed aside in the heat of battle returned even more intensely than before. Men who witnessed battlefield casualties, the treatment of remains, and the very real possibility of an anonymous death felt the inevitability of their own demise, and the fear of the time they too would become a casualty. The impact of a battle could linger for weeks, months, or years as bodies and evidence of combat remained visible to soldiers marching through or camping on old battlefields. Even more personal, names absent at daily roll call were a constant reminder of the losses they had suffered, and those they might suffer in the future.

For more on the mental stress of fighting the Civil War, read Mental Stress in the Union Army.

Kathleen Logothetis Thompson graduated from Siena College in May 2010 with a B.A. in History and a Certificate in Revolutionary Era Studies. She earned her M.A. in History from West Virginia University in May 2012. Her thesis “A Question of Life or Death: Suicide and Survival in the Union Army” examines wartime suicide among Union soldiers, its causes, and the reasons that army saw a relatively low suicide rate. She is currently pursuing her PhD at West Virginia University with research on mental trauma in the Civil War. In addition, Kathleen has been a seasonal interpreter at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park since 2010 and has worked on various other publications and projects.