Reforming a Nation, Saving the Union: The Development of Eastern State Penitentiary

/At the turn of the 19th century, the United States’ foremost democratic thinkers were not just focused on refining their government. Instead, they looked widely at the nation and its institutions, agonizing over how to best create a respectable, responsible, republican citizenry. Consequently, the 19th century witnessed a myriad of different reform movements aimed at perfecting every aspect of society. Reformers obeyed no boundaries, instructing people on everything from raising their children to how to properly compose a love letter. All of these things, they believed, were of the utmost importance because they relied on the virtue of the people; a nation founded of, by, and for the people, depended on the virtue of its citizenry. We know that eventually this system would break down. Less than one hundred years after its founding, the United States would dissolve into civil war. Democracy would fail and that failure would come at the cost of over 750,000 American lives.

In the early 19th century though, Americans were intensely concerned with avoiding any such outcome. Secession and civil war were not uncommon threats, both were used as bargaining chips long before South Carolina seceded from the Union in 1860. However, secession and civil war were outcomes to be feared, not sought after. Consequently, the greatest minds in the country endeavored to ensure stability and unity could be maintained. A perhaps surprising lens through which to understand early American development, the penitentiary system embodied the conflicting impulses with which leaders set about bettering their young nation.

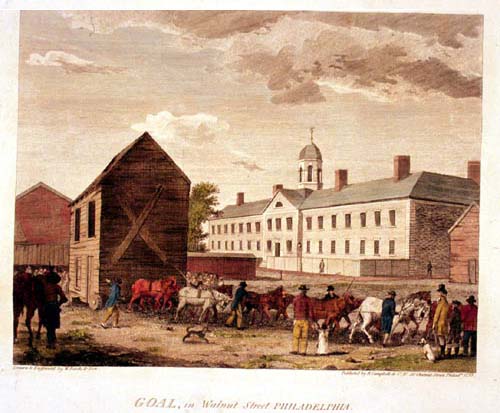

As Americans considered what they should and should not keep from the old systems in Europe, their attention fell quickly to what we would term criminal justice. Prior to the Revolution, the colonies utilized punishments that might look familiar to students of Civil War era military discipline – public shaming, branding, corporal punishment. Prisons were little more than overcrowded holding facilities where the guilty of all ages shared an unregulated space. Understandably, reform-minded observers saw this as a den for breeding criminals rather than an institution that would improve the country.

Notable figures like Benjamin Rush focused their sights on the prison system in Philadelphia just prior to the turn of the century. Finding that the system could not be reformed but rather needed to be completely overhauled, they founded the Society for Alleviating the Miseries of Public Prisons and set about planning a new facility. The ultimate results of their efforts, Eastern State Penitentiary, received its first inmate, Charles Williams, in 1829. This state of the art building took years to plan, and was still under construction when it opened.

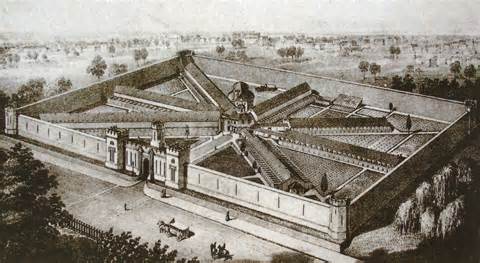

This new penitentiary, as the name implies, was founded on a basic belief that humans were inherently good and that it was the negative influences of the world and society that ultimately corrupted an individual and drove them to a life of crime. With this premise driving their decision making, the Society for Alleviating the Miseries of Public Prisons sought to create a space where criminals could contemplate their actions, separated from damaging influences, and determine to right their behavior. Those admitted to Eastern State found themselves inside a building that looked like a castle on the outside (because what did early Americans fear more than monarchy?) but a cathedral on the inside. The system of separate confinement implemented at Eastern State sought to ensure that inmates were kept away from other criminals, but guaranteed contact with “better” influences like the warden, the moral instructor, and religious leaders from a variety of denominations. Inside their cells, where residents spent twenty three hours of the day, they could labor at a variety of tasks from shoe making to learning how to read and write. Advocates of the system hoped that given the skills they needed for success outside of the penitentiary’s walls, inmates would turn to a life of honest labor and not return to a life of crime.

Even the architecture of Eastern State reflected this central ideology. Cell blocks radiated from an interior hub, allowing a guard to stand at the center of the building and look down each block but not into the cell. Entrances to the cells were on the outside, through adjoining exercise yards, and the only access from the interior of the building was a small feeding hole through which meals could be passed. Unlike some similar looking prison designs, most notably the panopticon which allows for constant supervision, Eastern State’s residents were left to the observation of God. In fact, skylights within each cell gave inmates a physical point of focus to allow for religious contemplation.

Guards closely monitored the morality of inmates above all else. Punishments attempted to control and correct infractions and the warden kept a daily journal chronicling how he and his staff handled each episode. In order to maintain a strong sense of oversight, the warden reported annually to a committee in the Pennsylvania state legislature.

These reports suggest an accute awareness of the monumental precedent the founders of Eastern State were setting for criminal reform in the United States. “Cherry Hill,” as it was sometimes known, was the first true penitentiary established in the country and from its founding it was plagued by critics from all sides. Perhaps more importantly, the separate system competed with the less regulated congregate system, which operated primarily in New York’s infamous Sing Sing prison and allowed for silent group labor. As Americans sorted through a new frame of government, they also sought to determine how to best administer their institutions.

Unfortunately for Eastern State, the pressures of a growing nation set in almost before the prison opened, and consequently the system struggled to maintain its lofty ideals. Its development presents an important example of the ways in which early Americans sought to create stability in the midst of constant growth, change, and volatility. Eventually, we know, the nation would give way to these pressures, erupting in a devastating civil war. Likewise, Eastern State would compromise on its founding principle of separation at the same time the nation crumbled into armed conflict. In a series of upcoming posts we will examine how those pressures would affect reform inside the United States’ first penitentiary.

Becca Capobianco is an educational contractor with Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park and an adjunct faculty member at Germanna Community College. ©

Sources and Additional Reading:

Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania State Archives, Records of the Department of Justice, Record Group R-15.

Warden’s Daily Journals, 1829-1961.Roll 2, volume 1

Convict Reception Registers, 1842-1929. Roll no. 2

Descriptive Registers, 1829-1903. Roll no. 2

Letters to and from Prisoners, 1845.

Carey, John H. "France Looks to Pennsylvania: The Eastern State Penitentiary as a Symbol of Reform." The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 82 (1958): 186-203.

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: the Birth of the Prison. New York: Pantheon Books, 1977.

Halttunen, Karen. Confidence Men and Painted Women: a Study of Middle-class Culture in America, 1830-1870. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1982.

McKelvey, Blake. American Prisons: a History of Good Intentions. Montclair, N.J.: P. Smith, 1977.

Johnston, Norman , Kenneth Finkel, and Jeffrey A. Cohen, Eastern State Penitentiary: Crucible of Good Intentions, Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art for the Eastern State Penitentiary Task Force of the Preservation Coalition of Greater Philadelphia, 1994.

Kahan, Paul. Seminary of Virtue: the Ideology and Practice of Inmate Reform at Eastern State Penitentiary, 1829-1971. New York: Peter Lang, 2012.

Lystra, Karen. Searching the Heart: Women, Men, and Romantic Love in Nineteenth-Century America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989.

Mintz, Steven. Moralists and Modernizers: America's pre-Civil War Reformers. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995.

Rothman, David J. The Discovery of the Asylum: Social Order and Disorder in the New Republic. Boston: Little, Brown, 1971.

Teeters, Negley K., and John D. Shearer. The Prison at Philadelphia, Cherry Hill: the Separate System of Penal Discipline, 1829-1913, New York: Published for Temple University Publications by Columbia University Press, 1957.