Roundtable: What Civil War Topics Deserve Greater Attention?

/In our first-ever Roundtable this summer, we asked Civil Discourse's scholars what event most influenced the outcome of the Civil War. Our answers were wide-ranging, but they would have been familiar to many of our readers: the Emancipation Proclamation, the Battle of Antietam, the fall of Atlanta, and more. Today, we shift our attention to areas overlooked or left behind by scholars, asking our panel:

What Civil War topics deserve greater attention from historians and scholars?

Becca Capobianco:

David Blight, standing at Appomattox Court House on the 150th anniversary of the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia, pointed out, “this was a military surrender, not a political treaty.” The verdicts of Appomattox, Blight continued, were not settled in April of 1865. Indeed, they were negotiated and renegotiated through the tumultuous years of Reconstruction, and further. Look at our headlines today and we can still see that those verdicts are not yet settled.

I am not sure there is a particular area of the Civil War that deserves greater attention so much as it is necessary for us to expand our understanding of the war as more than a military conflict. Appomattox, Bennett Place, and the myriad smaller surrenders that occurred in the wake of Lee’s army laying down arms finished the organized martial struggle we associate with the Civil War, 1861-1865. However, I think as historians we need to look at our scholarship as that of an era, one that began before 1861 and lasted beyond 1865 and left the United States floundering to find stability, identity, and a new normal in an increasingly unrecognizable nation. Complicating that effort was the sheer trauma of what they had just experienced, a war so devastating and unexpectedly brutal that many hoped – and still hope – to leave it on the field at Appomattox. But trauma like that cannot be laid down and forgotten, it persists, and it most certainly lasted not just for the soldiers who left part of themselves on the battlefield, but for the millions of non-combatants who found war on their doorsteps in all of its complex forms.

Consequently, I would suggest that it is necessary to take a holistic view of the era and further investigate the ways that the trauma of the war affected the political and memorial landscapes that developed in its wake. To examine not just what were the convoluted memories Americans held dear and recorded in stone on the battlefields, but why those memories were necessary to help them make sense of what had happened. To study how the subsequent, and indeed almost immediate, shifts in thinking about manhood, citizenship, and nationhood were inextricably tied to enduring questions unearthed by four years of war.

Katie L. Thompson:

With all that has been written already on the American Civil War, there is still so much we can discover and reinterpret with each generation of historians. We are fortunate in this field because the Civil War generation left us with an amazingly large record of written and material resources to study. As new fields of study open, historians have more and more possibilities in what scholarship they can produce with this plethora of materials.

One research area with a lot of potential is the merging of military history with other sub-fields: cultural, social, economic, etc. The place of military history in the field has been debated recently, but it provides the base for more scholarship. Because we now have a solid field in cultural and social history, there is a lot of potential for scholarship that sees military history through those lenses. This is already beginning in the “new military history” field, but there are more ways historians can use military history as a basis for a cultural, economic, or political study. Updating traditional military histories (that are usually top-down or tactics-based) to reflect the field of soldier studies (presenting military history from ground level through the experiences of soldiers) is another branch of this type which offers good potential.

Civil War memory is a field rich with potential, especially with the current debates over the role of Confederate memory in American culture. There is room for more scholarship on how the Civil War and its legacy have been interpreted over the last 150 years and have been used in society during that time. Studies of this unique legacy can help current Americans understand how we arrived at the debates of today and provide insight into how to continue moving forward.

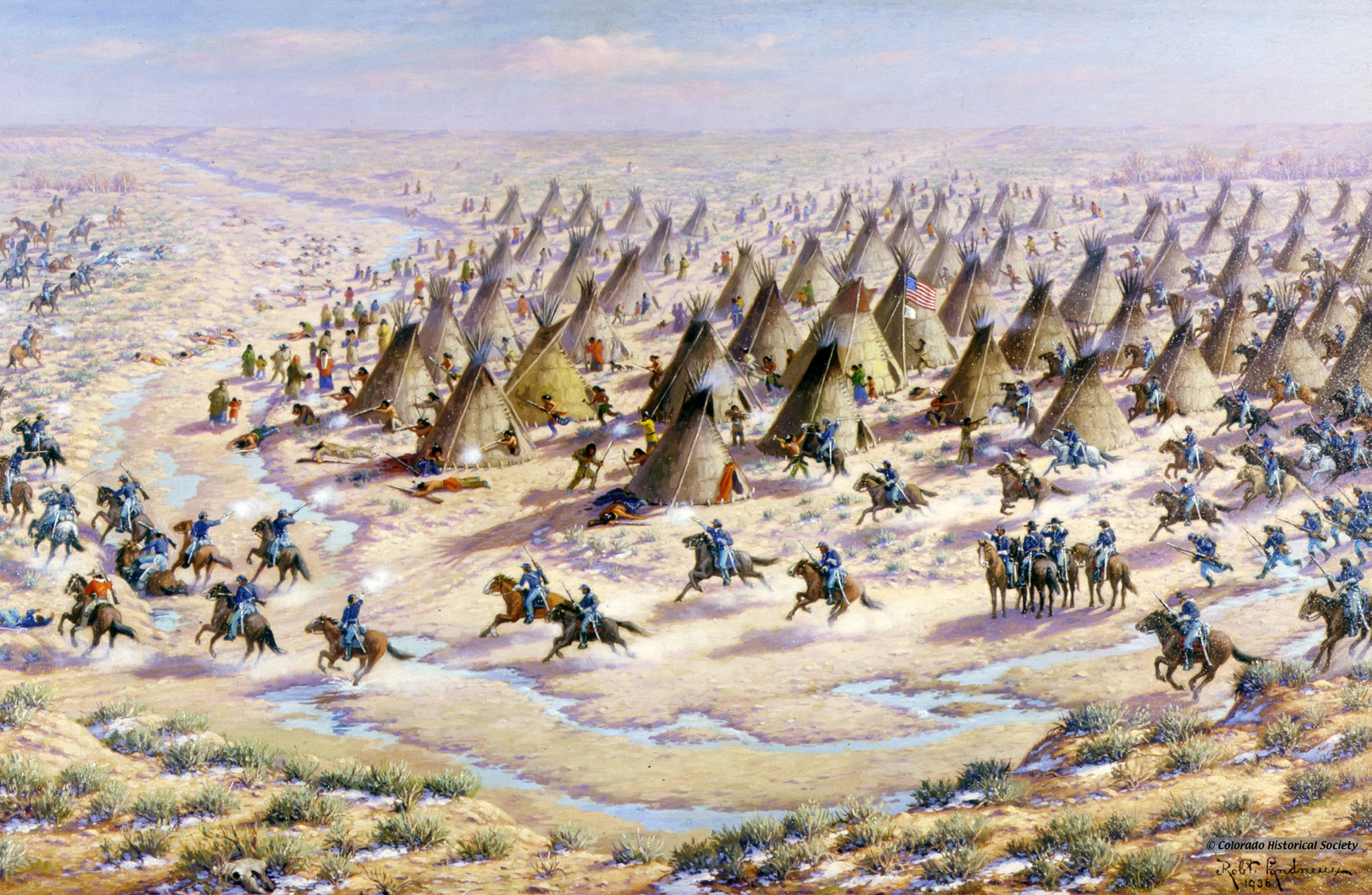

A third section of study that deserves more attention is foreign policy and continental/international perspectives of the Civil War period. It is very easy to study the Civil War in the bubble of the eastern and western campaigns without realizing that other parts of the continent and world were reacting to the Civil War or were involved in some way. It is telling that the Tom Watson Brown Book Prize (awarded by the Society of Civil War Historians) in 2014 was awarded to Ari Kelman’s book on the Sand Creek Massacre. There is a lot of potential, especially in international and foreign policy studies, for new scholarship on the Civil War era.

The last topic that could use more attention is Reconstruction. Not that books on the Reconstruction Era are lacking, but it is sometimes treated as a separate topic from the Civil War. Because Reconstruction provides the biggest legacy of the war (with the end of slavery and the rebalancing of a society shaken to the core by emancipation) more scholarship should analyze how the war transitioned into Reconstruction and how Reconstruction created the Civil War memory that we are familiar with.

New military history, memory and its current affects, international and continental perspectives, and new analysis of Reconstruction are only a few of the many directions Civil War scholarship can go. New interpretations and inter-disciplinary studies may steer the field in directions completely unimagined at this point.

Zac Cowsert:

Despite historians' current penchant for guerrilla studies and examinations of the homefront, we know fairly little about the plethora of refugees in the American Civil War. To be sure, the conflict produced plenty. Whether fleeing Fredericksburg as battle loomed, watching Atlanta burn in the distance, or being forced to relocate by enemy forces, civilians often found themselves destitute and homeless during the war.

Mary Massey's 1964 Refugees in the Confederacy, although dated and anecdotal, probably remains the broadest examination of the refugee experience available. Massey estimates there were 200,000 refugees in the Confederacy. More recently, Yael Sternhell's Routes of War devoted space to the Confederate refugee crisis, arguing that "Flight, both black and white, gnawed away at the social order of the Confederacy until it finally came tumbling down."

These works beg further questions that scholars have only barely begun to explore. What caused civilians to flee their homes and lose their livelihoods? What were their common experiences? Where did they flee to, and why? When, if ever, did they return home? What did they return home to? What were the experiences of Northern refugees (those who fled from John Hunt Morgan, or watched Chambersburg burn)? What strain did refugees place on local and national governments? Did "flight" truly undermine the Confederacy?

These are big questions, important questions, and questions I hope scholars will begin to answer.

Becky Oakes:

Topics in academic literature concerning the long Civil War era have expanded impressively in the last half-century, moving from detailed battle narratives, biographies of big men, and the triumphal narrative of American history to works on slavery, soldier motivation, and collective memory. There are studies on gender relations, material culture, and even grieving and death. Previously ignored topics such as the physical, psychological, and environmental impacts of the war are now being thoroughly explored.

However, most of what is produced for and consumed by the general public is still big men, battle narratives, and triumphalism. If there is a gap in academics’ writings of the Civil War, the question is not what, but for whom.

Academics express concern that many Americans have trouble identifying slavery as the cause of the American Civil War. But rarely are they seen doing much about it in writing, expecting their ideas to eventually “trickle down” to the American public. However, there are a large number of Americans who are interested in the Civil War, read about it extensively, and often thoughtfully question what they are learning. In terms of written scholarship, what is available for these people?

Many Americans who want to learn more about the Civil War than what they were taught in school embark on their journey at a Civil War museum or battlefield. However, the gift shops at these sites mostly contain books on local interest, specific battles, famous historical figures, and fictional works. Some claim that this is all the public wants to read. Throughout my experience working with the public in the last few years, I have come to fundamentally disagree with this view. Although many, including myself, enjoy reading about battles and generals, people want to understand the bigger picture as well. And works that discuss this bigger picture, while subsequently being consumable and engaging to read, are slim.

There are, of course, a few exceptions to this rule. Entities such as the National Park Service have published a short books or a series of articles on some of these larger ideas. A monograph or two with a flashy title or a particularly dynamic topic may make it onto the bookstore shelves. Occasionally, a store manager will choose recognize a certain academic’s work as well written and digestible. But for the most part, visitors can more easily purchase four separate biographies on Stonewall Jackson before they purchase a book on the causes of the Civil War.

The primary criticism academics have of popular histories is that they are not written academically. There seems to be an easy solution to this problem.

Most of us already recognize the academy extends beyond the ivory tower. Historians who work in museums and on battlefields still read, engage with, and contribute to the growing body of literature about the Civil War. And every day, they translate those big and important ideas found in academic texts into something digestible for the public. Anyone who does not think public history is an academic exercise should try explaining why slavery existed to a five year old, or the Lost Cause to a European visitor who does not understand the veneration of Confederate leaders. Every day, good historians interpret those huge and complex concepts to the public.

We can talk about hegemonic power structures without using the word hegemony. We don’t always need to quote Foucault, and I doubt any of us would dream of doing so on a walking tour. So why is it that when we put the proverbial pen to paper, we turn into jargon monsters?

The answer is because we are primarily writing for other academics. Which we should certainly continue to do. But we need to start writing for the public too.

Roundtable Contributors:

Becca Capobianco received her master's degree in American and public history from Villanova University. Becca worked as an educational consultant at Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park; she now works at Great Smoky Mountains National Park. She has worked at the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia, the Mercer Museum in Doylestown, PA, and as an adjunct faculty member at Germanna Community College.

Zac Cowsert is currently pursuing his doctorate in American history at West Virginia University, where he also earned his master's degree. His research focuses on the Civil War experience of the Five Tribes of Indian Territory. Zac attended college at Centenary College of Louisiana in Shreveport, and he has worked for the National Park Service at Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park.

Becky Oakes, a graduate of Gettysburg College, recently completed her master’s degree in 19th-century U.S. history and public history at West Virginia University. She will begin her doctoral work at WVU in the fall. Becky’s research focuses on Civil War memory and cultural heritage tourism, specifically the development of built commemorative environments. She also studies National Park Service history, and has worked at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park, Gettysburg National Military Park, and the Civil War Institute at Gettysburg College.

Katie Logothetis Thompson earned a BA in History from Siena College in her homestate of New York. She received her MA in History from West Virginia University, and she is now a doctoral candidate at WVU. Her research explores how Civil War soldiers attempted to cope with their wartime experiences. Katie has worked for the National Park Service at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park in Virginia in addition to other academic and public history projects.