The Fall from Little Round Top: Gouverneur Warren and the 1863/1864 Virginia Campaigns

/In July 1863, Gouverneur K. Warren was considered the hero of Gettysburg for finding the crucial position on top of Little Round Top and directing troops to hold it minutes before the Confederate attack hit what would have been the unprotected flank of the Union army. Less than two years later, by the end of the war, Warren was humiliated by being relieved of command and spent much of the rest of his life trying to reclaim his good name. The Virginia campaigns of late 1863 and 1864 proved Warren’s downfall as his superiors began to question his ability to fight in the aggressive style adopted late in the war.

After his actions at Gettysburg, Warren was promoted to major general and placed in command of the II Corps in the absence of Winfield S. Hancock, who was recovering from a wound received on the third day of fighting at Gettysburg. Further distinguishing actions at the Battle of Bristoe Station led to a brevet to major general in the regular army. Consequently, Warren was in a good position when General George G. Meade led the Army of the Potomac into a fall campaign against General Robert E. Lee in northern Virginia.

Following the Bristoe Campaign, which ended with both armies around the Rappahannock River west of Fredericksburg, Lincoln pressured Meade to keep on the offensive. Thus, instead of entering winter encampments, the Union army pressed southward towards Lee who was positioned below the Rapidan River in Arange County. After considerable maneuver and delay, on November 27, 1863, Warren’s II Corps broke camp, marched down the Orange Turnpike (in the area of the Wilderness), turned west towards Robinson’s Tavern, and deployed along the high ground west of the tavern. Although Warren’s men were in position the rest of the army was slow to reach the field and Meade cautioned Warren to delay fighting until reinforced. Thus the day was wasted by delays and uncoordinated attacks, largely in action at Payne’s Farm.

Trying to regroup, Meade planned to attack at daybreak on November 28th. Overnight Lee gained enough intelligence of the Union’s movement that he had his men fall back to the high ground west of Mine Run and entrench in preparation of the Union attack. When Meade ordered the II Corps forward in the morning they found the Confederates dug in, halting their momentum. Another day was wasted as Meade surveyed the new Confederate line and readjusted his tactics, giving Lee further time to strengthen his position.

On the evening of the 28th, Warren suggested a move on the Confederates’ right flank in order to find a vulnerable point to attack or try to turn the enemy’s flank and force action (hopefully a retreat) from Lee. At this point Meade trusted Warren’s opinion since he had showed good judgement at both Gettysburg and Bristoe Station, and Warren commenced his proposed movement the next morning.

As Warren pushed his troops forward and prepared to assault the Confederate line, reports came in that General J. E. B. Stuart was attacking Brigadier General David Gregg’s cavalry behind the Union lines. This possible flanking attempt by the Confederates caused Warren to halt his men just before they made their final assault. By the time the cavalry threat had cleared, Warren still faced a favorable position but daylight was waning quickly (being the end of November prior to daylight savings time) and he could not attack in the dark. Yet again, delays stopped Union momentum and allowed the Confederates time to strengthen their position.

Meade and Warren agreed to continue the assault on the morning of the 30th with an opening artillery attack on the Confederate right at 8:00 AM followed by Warren’s attack at 9:00 AM. The artillery bombardment began as planned, but the infantry, including Warren himself, surveyed the entrenched Confederate position with dread. Many men predicted a repeat of the slaughter at Fredericksburg and prepared themselves for a battle with little chance of survival. Warren decided to call off the infantry attack on his own, being too far away from Meade’s headquarters to quickly seek his advice. Warren’s message reached headquarters right before the assault was planned to begin forcing Meade to suspend the whole action and send aids out to assess the situation. Meade joined Warren at the latter’s position to survey the Confederate line and, after meeting with him, officially cancelled the assault.

At a council of war that night Meade and his subordinates decided that the enemy was too entrenched to continue the assault. The Union army returned north of the Rapidan River and both forces settled into winter camps. Meade would privately blame Warren for the failure of Mine Run and would receive much of the pressure from Washington about the botched campaign, but Warren largely escaped censure for his actions. Following the campaign he wrote to his wife, Emily: “Don’t let the late movements worry you. Thank heaven they were all right as far as I was concerned and the failure was to the plans not having been carried out by those with us, and then it fell upon me to decide we should not waste our men’s lives in hopeless assaults to make up for previous blunder. Rest assured I did right and all in the army will say so.”

The men under Warren certainly believed he had made the correct decision and many felt grateful to him for valuing their lives over his orders to advance. J. H. Lockwood of the 7th (West) Virginia, one of Warren’s regimental commanders, wrote that Warren’s decision to cancel the attack was “one of the noblest acts of humanity on your part ever enacted…a mark of Generalship worth of great credit.” Colonel Rufus Dawes agreed that “[t]he slaughter would have been great and we feel thankful to have been spared.” Perhaps the colonel of the 1st Pennsylvania Reserves put it most dramatically when he wrote: “The army, perhaps the Union cause, was saved, due to the clear judgement and military skill of those grand officers, Meade and Warren…Had the two armies fought at Mine Run the result would have been the greatest slaughter in the history of the United States.” While the soldiers and officers under Warren praised his decision to cancel the assault on Mine Run, his actions during the campaign had damaged the high opinion Meade once had of the general. The Overland campaign of 1864 would do nothing to repair Meade’s attitude towards Warren.

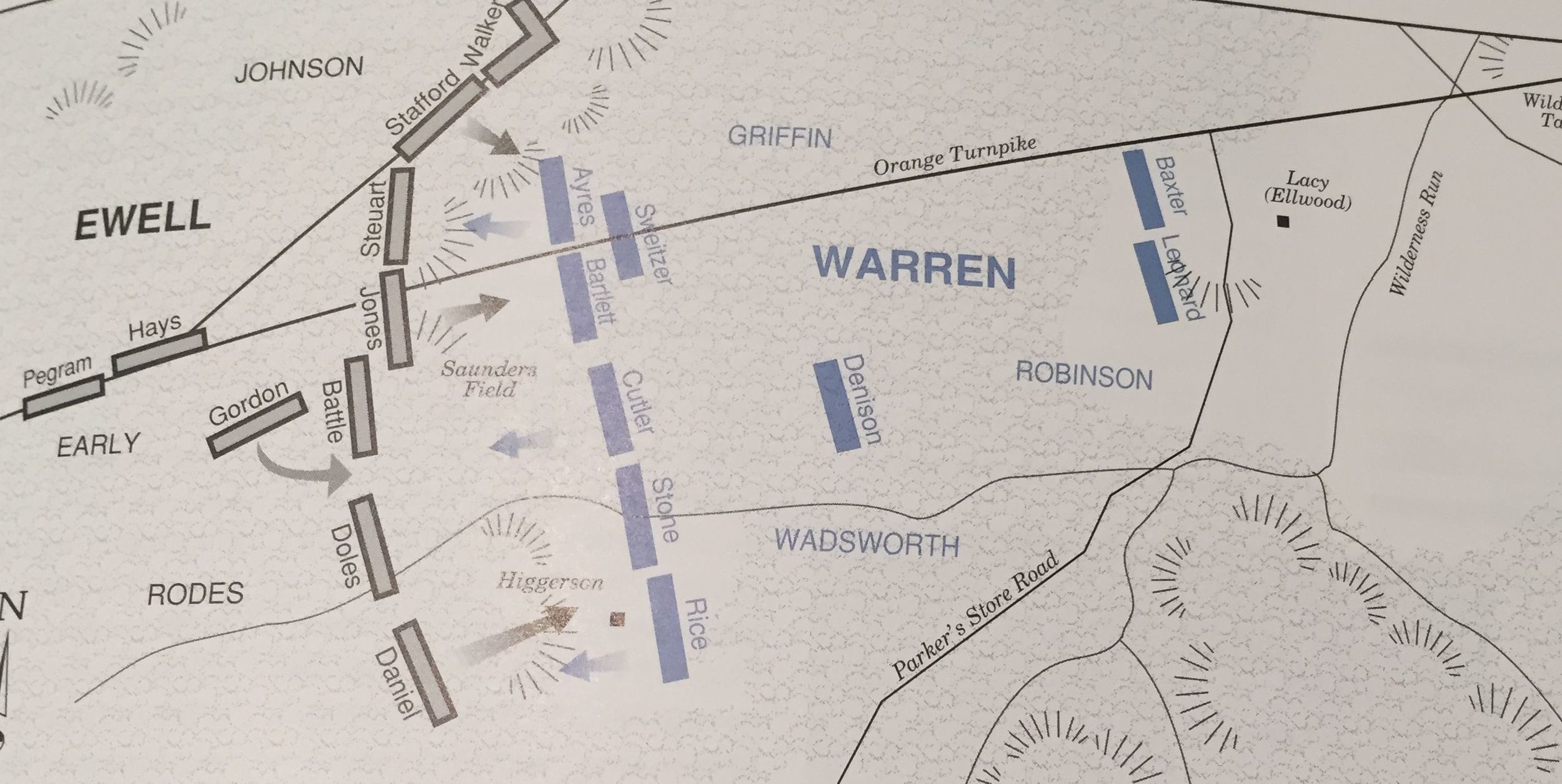

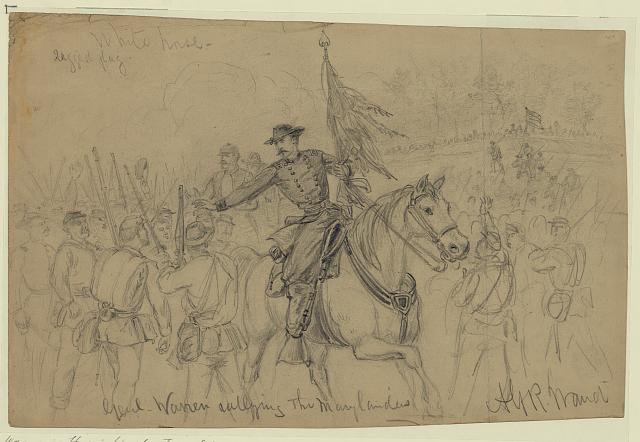

The spring campaign of 1864 opened in the tangled woods of the Wilderness in northern Virginia, not far from the Mine Run battlefield of the previous fall. On May 5, Warren, now at the head of the V Corps, quickly encountered troops from Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia along the Orange Turnpike. Lee had acted quickly to the Union movement, hoping to trap them in the Wilderness where Meade’s numerical advantage and artillery would be cancelled out by the terrain. Upon receipt of Warren’s report, General Ulysses S. Grant—now commander of all Union armies in the field, traveling with Meade’s Army of the Potomac—realized that Lee was probably trying to delay them on their march south. Grant sent a message back to Warren stating: “If any opportunity presents itself for pitching into a part of Lee’s army, do so without giving time for disposition.” Meade added his own order to Grant’s, “Attack as soon as you can” and coordinate with Brigadier General Horatio Wright’s IV Corps division coming up behind Warren. Warren was not pleased with the orders, later calling them “the most fatal blunder of the campaign.” His corps was scattered through the woods and his right flank, past Brigadier General Charles Griffin’s division at the edge of Saunders Field, was “up in the air” and unprotected from a flank attack.

Warren stalled for time, trying to get his corps into a better position to attack the Confederates. He sent messages to his two divisions in the woods south of the Turnpike to move north and connect with Griffin’s men for a united line. Brigadier General Samuel W. Crawford, in company of the division farthest south, was reluctant to move. His men had taken up position at the Chewning farm, one of the few clearings in the Wilderness that was also high ground with a clear view overlooking the Orange Plank Road. It took a second order to Crawford to get him to move his men, all while Grant and Meade were pressuring Warren to attack Lee. From headquarters Grant and Meade could not see the difficulty Warren was having pulling his men into position and they thought the Confederate force was a small scouting party or rear guard and they continued to push Warren to attack. As Warren continued to wait for the VI Corps to come up and support his right side, Grant grew impatient and questioned the bravery and fortitude of Meade’s army. Having only heard reports about the Army of the Potomac from afar up until this point, Grant questioned if they were overly scared of Lee and afraid to fight. By 11:30 AM patience had run out and Meade ordered Warren to attack or else, advised the courier delivering the order, Warren would be cashiered and relieved of command. With no other option, and still unsupported on the right, Warren gave the order to advance.

Around one in the afternoon, Griffin’s division surged forward across the Saunders clearing while Wadsworth and Crawford’s men struggled through the dense Wilderness to engage with the Confederates. The difficulty of the terrain led to confusion and the inability to maintain battle formation and the weakness of Griffin’s right flank allowed Confederates to wrap around the Union troops in Saunders Field with enfilade fire. Men got lost, officers lost command over their men, and Warren’s entire attack fell back towards the Lacy House (Ellwood) in defeat.

While the V and VI Corps would see some minor fighting on May 6, Warren’s part in the Battle of the Wilderness was primarily over and his main effort was a failure. In his short-lived offensive the V Corps lost more than three thousand casualties, some that had burned to death in the fires that consumed the thick foliage of the Wilderness. The battle shifted south to where General Winfield S. Hancock’s II Corps battled General A. P. Hill’s troops for control of the crucial Brock Road-Plank Road intersection. Warren was directed to attack again on the morning of the 6th in support of Hancock’s attack to the South, and Meade reported that his troops were engaged, but Warren never pushed forward in a full assault. He deployed his artillery and pushed towards the Confederate lines but never attempted an assault against the enemy lines, fearing the same fatal situation as the day before.

As the Battle of the Wilderness fell into stalemate, General Grant decided to use his position on the Brock-Plank intersection to push south and force a Confederate move. On the evening of May 7, Warren’s V Corps lead the order of march towards Spotsylvania Court House. It was crucial to Grant’s plan that the Union army reach Spotsylvania first, but Warren’s men encountered several obstacles during the night, including the sleeping men of the II Corps and Confederate cavalry around Todd’s Tavern. These delays and an overnight march by the Confederates (who could not find a place to bivouac in the burning woods) caused Lee’s men to reach Spotsylvania in just enough time to get in front of Warren’s men and block the Union movement south.

When the V Corps troops entered the clearing around the Spindle Farm on the morning of May 8, in front of the ridge named Laurel Hill, Warren assumed they were facing the remaining cavalry that had been dogging their advance since Todd’s Tavern. Instead, they faced Longstreet’s infantry who had just slipped into their places along the high ridgeline, relieving the Confederate cavalry. For the rest of the morning, Warren acted uncharacteristically when compared to his performance in the last few engagements. As his brigades arrived from the march Warren threw them into attacks piecemeal, without waiting to form up a substantial force. This led to several failed attacks by his men already weary from two days of fighting and an overnight march. By the afternoon it was clear Warren could not break through the Confederate lines with his weary and battered troops and he had to wait to the rest of the army to arrive, giving Lee time to also bring up the rest of this army and dig in, setting the stage for the extended fighting north of Spotsylvania Courthouse.

It is clear at this point that Warren was feeling the pressure from Meade and Grant to be more forceful in his command. While his cautious action at Mine Run had earned the affection of his men, Meade’s opinion of the General had lowered, and Warren’s stalling at the Wilderness had added Grant’s ire to Meade’s growing distrust. With Meade and Grant’s headquarters stationed just to the rear of the V Corps position along the Orange Turnpike at the Wilderness it is very likely that he had heard talk criticizing his slowness or implying his inability to handle the job and fight against Lee in Grant’s new aggressive style. Add to this the fact that he was just as tired as his men after several days of fighting and marching.

Warren’s efforts on May 8 were failures and cost the Corps heavily. Through May 9, they held their position in front of Laurel Hill with General John Sedwick’s VI Corps while the rest of the Union army came up and filed into line beside them, extending to the east. Grant ordered them to make a demonstration at Laurel Hill, in support of action on both flanks of the Confederate army as Grant’s probed for a weakness in the Confederate line, but they were easily repulsed and Meade’s attempts to flank Lee’s army met similar results.

Grant regrouped on May 10; believing that Lee had shifted men to the flanks to ward of the attacks of the previous day, he ordered a diversion by the Po River, on the left flank of the Confederates, to prepare for a concentrated assault along the entire line at 5:00 PM. Grant intended an assault along the entire line with the V Corps attacking the Confederate left, Brigadier Gershom Mott’s Division attacking at the tip of the Mule Shoe Salient, Burnside’s IX Corps on the Confederate right, and a highly concentrated attack by Colonel Emory Upton of the VI Corps in the center. The goal was to pressure the entire line in order to find a weakness that Grant could exploit against Lee.

But Warren was anxious to redeem himself and repair his reputation with Grant and Meade. His failures on May 8 and the questions of his fighting spirit at Wilderness sat heavily on his mind. With General Hancock busy with the fighting at the Po River, Warren remained in charge of the Laurel Hill region and he petitioned Meade to attack before the scheduled assault. For reasons unknown, Meade consented and Warren led portions of the V and II Corps against Laurel Hill at 4:00 pm. The unsupported attack was another failure from Warren and his men fell back, exhausted from their attempt. Grant had to postpone the coordinated assault until 6:00 PM, one hour later than scheduled, in order to let Warren’s men rest.

Warren’s actions caused the complete disintegration of Grant’s coordinated assault. General Mott, at the tip of the Salient, did not receive the orders that delayed the assault and attacked at 5:00 per the original plan. Unsupported, Mott’s men fell back in confusion. The only attack that moved forward successfully at 6:00 was the small, concentrated attack led by Colonel Emory Upton who had hand-selected twelve regiments and placed them in a compact “battering ram” formation to pound into the Confederate line. His plan was to breach the enemy line and then spread sideways to roll up the lines and create a break that could be exploited by Grant. At first his plan worked perfectly, but because his attack was unsupported by the other assaults that were supposed to occur at the same time, the Confederates could reinforce the line and push his men back. Burnside advanced cautiously at 6:00 but never attacked and the men under Mott and Warren did not attack again, being too worn out from their previous assaults.

Despite the losses, Grant was optimistic because Upton’s limited success gave him the idea for his grand assault on the Confederate Mule Shoe on May 12th. For Warren, however, the beginning of the Overland Campaign secured his fall from grace in the eyes of his commanders, even though he would remain in command of the V Corps for the majority of the rest of the war. Despite Warren’s eagerness to push forward at Spotsylvania, the opinions of Grant and Meade had already settled on his hesitancy to act in previous battles. This, along with his tendency to second-guess his superiors and offer unwanted advice, eventually led to his being relieved of command after Five Forks at the end of the Petersburg Campaign. His hesitancy to follow orders where he could see no possibility of success came from the most noble of places; he did not want to send his men into doomed assaults to be mowed down for no gain. But the plans of Grant and Meade demanded such action, and his hesitancy eventually brought censure instead of praise. He was a general who led men well on the field, but could not see the big-picture strategy that Grant did. According to Warren biographer David Jordan, Warren was prouder about his actions at Mine Run than those at Gettysburg.

Resigning his position in the volunteer army, Warren remained in the Army Corps of Engineers until he died and constantly worked to clear his name from any wrongdoing in the war. He repeatedly petitioned for a court of inquiry into the charges against him, especially those from Five Forks where he lost his command. President Rutherford B. Hayes finally convened such an inquiry in 1879 (Grant ignored Warren’s request during his terms in office) and the inquiry found that his removal from command had been unfounded. Unfortunately for Warren, the results from the inquiry were not published until November 1882, three months after his death.

Kathleen Logothetis Thompson graduated from Siena College in May 2010 with a B.A. in History and a Certificate in Revolutionary Era Studies. She earned her M.A. in History from West Virginia University in May 2012. Her thesis “A Question of Life or Death: Suicide and Survival in the Union Army” examines wartime suicide among Union soldiers, its causes, and the reasons that army saw a relatively low suicide rate. She is currently pursuing her PhD at West Virginia University with research on mental trauma in the Civil War. In addition, Kathleen has been a seasonal interpreter at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park since 2010 and has worked on various other publications and projects.

Sources and Suggested Reading:

Graham, Martin F., and George F. Skoch. Mine Run: A Campaign of Lost Opportunities; October 21, 1863-May 1, 1864. Lynchburg, VA: The Virginia Civil War Battles and Leaders Series, H. E. Howard, Inc. 1987.

Jordan, David M. “Happiness Is Not My Companion”: The Life of General G. K. Warren. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001.

Rhea, Gordon C. The Battles for Spotsylvania Court House and the Road to Yellow Tavern, May 7-12, 1864. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2005.

Rhea, Gordon C. The Battle of the Wilderness, May 5-6, 1864. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2004.