Not Who, But How: Civil War Loyalty

/At the root of any civil war lays loyalty. Internal conflicts, fought over everything from politics to religion, produce deep divisions amongst a nation’s populace. America’s Civil War was no exception, as it witnessed divisions along geographic, social, political, and racial lines. Not only did the war divide former countrymen, but these divisions were something that Americans talked extensively about throughout the war. As historian William Blair recently noted, in the Civil War North it is almost impossible to find a newspaper that did not discuss treason or loyalty in nearly every issue. Along with extensive discussion about loyalty and treason in local newspapers, these conversations carried over into the personal correspondences of contemporary men and women. I, like many other historians, have studied the issue of wartime loyalty, yet my research takes that subject in a different direction.

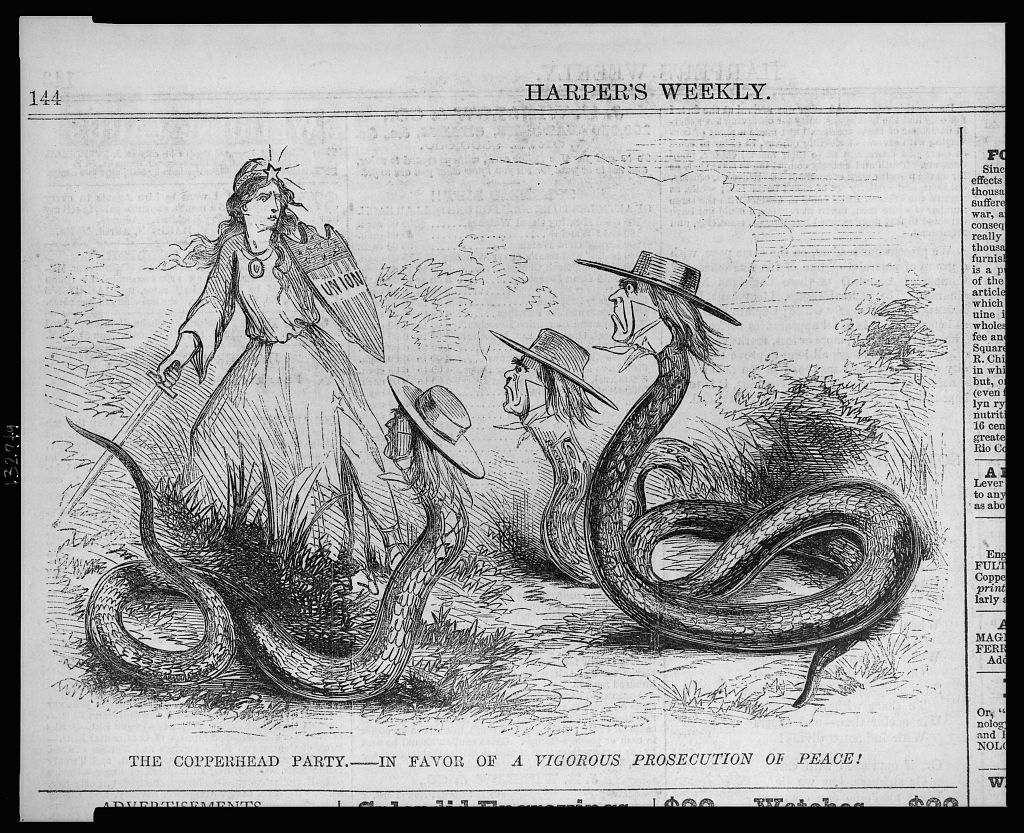

I approach the study of loyalty as a cultural historian, seeking to understand just how ordinary men and women conceptualized what it meant to be loyal as secession and war tore the nation apart. Traditionally, historians have defended select social, political, or ethnic subsections of American society. Historians of anti-war Democrats, such as Frank Klement, Arnold Shankman, and Robert Sandow argue that political opponents (often Republicans) and sometimes business owners besmirched the reputations of specific segments of society for political or economic gain. Consequently, these historians have argued that such actions distort our understanding of the Civil War’s political and social experience, unjustly positioning some groups as disloyal. Each of these scholars have been extremely helpful in detailing the experiences of dissent during the Civil War, but focused intently on explaining who was loyal during the conflict.

Yet how did Americans use loyalty as way to understand the Civil War and the chaos that surrounded them from 1861 to 1865? Allow me to offer up two examples that I believe help answer that question. The first comes from eastern Pennsylvania (specifically Berks, Bucks, Lehigh, and Northampton counties), where notions of loyalty divided primarily along partisan lines. Much like the rest of the North, Democrats and Republicans in eastern Pennsylvania united at the start of the war, but eventually they were pulled apart. Local residents understood this shift through their definitions of loyalty. Broadly speaking, members of both parties eventually came to believe that their party was the only loyal organization and consequently the only group capable of saving the nation. Democrats early in the war stated their support for the Lincoln Administration “in all just and constitutional measures,” but reserved the right to criticize the Republican leaders if they violated the Constitution. When Lincoln began increasing the federal government’s role in daily affairs (through increased taxes and conscription), as well as through emancipation of Southern slaves, eastern Pennsylvania Democrats began to view Republicans as fanatics, whose actions both violated the Constitution and eliminated any possible chance of reconciliation with the Confederacy. As a result, Democratic papers and individuals criticized the government harshly, which prompted a Republican response.

Acting on their own definition of loyalty, which required unquestioning support of the government, Republicans lambasted Democrats as turncoats and traitors whose sympathy for the South would hinder the Union war effort. This rhetoric reached a fever pitch in the Keystone State’s 1863 gubernatorial election and the 1864 presidential election. Some, like volunteer William Reichard, viewed Democrats as “traitors at home” who were “worse than the rebels, for the latter do their things openly, but the former are so base and deluded that they would (as you write) destroy the Government rather than see the Republican party in power.” Republicans viewed Democrats as disloyal and dangerous figures, who sought to undermine the Union war effort, support the Confederacy, and destroy the nation. Their lack of support for the Lincoln administration prompted accusations of disloyalty and fear over the prospect of Democrats being successfully elected. Comparatively, Democrats believed in both 1863 and 1864 they needed to gain power in order to “unite what fanaticism has disunited—to heal the deep cut thrust by Abolition traitors.” Republican policies, in particular the process of emancipation and the destruction of Southern slavery violated, for Democrats, the Constitution and what they believed were guaranteed rights that allowed for the owning of slaves. In both of these examples, members of both parties co-opted the language of loyalty for political gain, building off pre-existing political animosities. Loyalty was a way for them to encourage support for their party, while they positioned their opponents as disloyal and therefore dangerous to the very survival of the nation.

Residents of western Virginia (present-day West Virginia and its neighboring Virginia counties) constitute a second example, but one that associated less with political organizations and more with an individual’s moral character. From the time of Lincoln’s election through the Richmond secession convention and eventually the creation of West Virginia, these men and women judged the virtue of their family members, neighbors, and acquaintances in relationship to the side they supported during the war. An essential part of western Virginia's wartime experience was resistance to secession, sustained largely by elements of the northwestern part of the state. Many of Unionists pushed for and eventually seceded in proving their displeasure by breaking away from the Old Dominion and creating the state of West Virginia.

Out of this movement comes a clear example of how western Virginians tied loyalty and virtue together. In 1863, pro-state supporters attacked one member of the legislature, John J. Davis. A Clarksburg lawyer, Davis was a supporter of the Union, but ultimately stood against the formation of a new state, due in large part to the congressional requirement that slavery be abolished in West Virginia. Supporters of the new state launched a brutal attack against Davis via political pamphlets. The pamphlets associated the young lawyer with secessionism and support for Jefferson Davis. More specifically though, it laid out that while in 1861 Davis had been for the Union, by 1863 he was now a “black-hearted TRAITOR.” Accusing Davis of misrepresenting those who elected him, the pamphlet went on to ask “Why are all the scoundrels, liquor-sellers, liars, offer-seekers, nigger-holders against the Union?” The connection here was clear: because Davis opposed statehood, he was disloyal to the Union. Not only was he disloyal, but he was among the most contemptible elements of society. Statehood supporters used loyalty to discredit Davis, arguing that his lack of support for the new state classified him as one of society’s lowest individuals. Although different from the experiences in eastern Pennsylvania, the pamphlet against Davis conflated his lack of loyalty to the Union with a disreputable nature.

In both of these examples, loyalty was more than just a simple means of classifying who was loyal to the nation during the war. Rather it was a way in which contemporary individuals understood the war, though it was not the only way eastern Pennsylvanians or western Virginians conceptualized the Civil War. As I continue to write for Civil Discourse, I will return to the issue of loyalty from time to time, as I think it is a topic in need of greater attention. In doing so I will expand on many of these issues in greater detail, looking at how men, women, soldiers, politicians, and civilians all used loyalty—through the nicknames they applied to one another, how they appeared in newspapers, or how they mapped the loyalty of the individuals or places they encountered. I hope though, that after reading this, we might start to consider loyalty in broader terms, as a way individuals understood the social and political aspects of the war.

Chuck Welsko is currently a doctoral student in 19th-century American history at West Virginia University, where he also received his master’s degree. An alum of Moravian College in Pennsylvania, he has also worked for local museums and interned with the National Park Service. Chuck’s research focuses on the mid-Atlantic region, in particular the intersection between politics, rhetoric, and the conceptualizations of loyalty during the Civil War Era. ©

Sources and Further Reading:

Blair, William A. Malice Toward Some: Treason and Loyalty in the Civil War Era. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 2014.

Davis, John J. (1835-1916). Papers. A&M 1366. West Virginia Regional History Collection, West Virginia University, Morgantown, West Virginia.

Guelzo, Allen C. Fateful Lightning: A New History of the Civil War and Reconstruction. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Klement, Frank L. The Copperheads in the Middle West. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1960.

McPherson, James. For Cause and Comrades: Why Men Fought in the Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Palladino, Grace. Another Civil War: Labor, Capital, and the State in the Anthracite Regions of Pennsylvania, 1840-1868. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1990.

Paludan, Phillip Shaw. A People’s Contest: The Union & Civil War, 1861-1865. 2nd ed. Lawrence, Kansas: University of Kansas, 1996.

Sandow, Robert. Deserter Country: Civil War Opposition in the Pennsylvania Appalachians. New York: Fordham University Press, 2009.

Shankman, Arnold. The Pennsylvania Antiwar Movement, 1861-1865. Rutherford, NJ: Farleigh Dickinson University Press, 1980.