"A Sunken House with Nothing but the Roof Above the Tide:" Rebuilding the CSS Virginia

/On March 9, 1862, the famous duel between the ironclads USS Monitor and CSS Virginia (better known as the Merrimack) occurred at Hampton Roads. Both ships signaled the dawn of a new age in Naval tactics and architecture; however, the Virginia makes more of an impact on the navies of the world and is made more remarkable in the fact that she was built by a confederation with so few resources and had such a short career. The Virginia only lived for nine weeks between the time she was floated and her destruction; she spent only twelve days out of dry dock during those nine weeks, and was in battle for a total of about twelve hours. In that short time span and with the resources pulled together by a fledgling Confederate government, the CSS Virginia ushered in the next era of naval technology.

The idea of having a ship covered in metal was not a new idea in the nineteenth-century. The idea went back as far as the third-century BCE when the King of Syracuse sheathed his vessels in lead, probably to protect them from sea worms and marine growths. Norsemen would not cover their ships permanently with metal, but would line the sides with their ironbound and studded shields while they were rowing. In 1592, Korean admiral Yi-Sun used an iron-clad “tortoise ship” to repel a Japanese naval attack and in the 1780s the Spanish built floating gun batteries with iron-covered bulwarks to protect them.

In the nineteenth-century, five naval revolutions occurred that would factor heavily in the design and importance of the Virginia. The steam engine allowed for more maneuverability and power and broke the traditional resistance on the wind and currents. It also allowed ships to be heavier, important later on when the ironclads came into being. The screw propeller allowed the engines to be placed below the waterline where they were safer in battle. Also changing the face of battle were rifled artillery pieces that increased the range and accuracy of naval ordnance. The fourth revolution, the exploding shell, was one of the most important factors in the rise of the ironclad. In 1824, General Henri J. Paixhans, a French artillerist, developed the shell gun which fired a hollow shell filled with powder that would explode on impact. These four revolutions led to the fifth, that being the armored ship.

The experimentation that occurred in the 1840s using the five naval revolutions was cut off by the outbreak of the Crimean War, but improvement on those basic ideas flourished. At the beginning of the war, the vulnerability of wooden ships was vividly exposed at Stevastopol where the allied wooden fleet could not withstand the fire from Russian fortifications firing shells. Conversely, in 1855, Napoleon engaged three floating batteries in battle at Kinbun on October 15. These batteries withstood the Russian fortress fire and, returning fire, reduced the fort to rubble. Europeans saw the effect of shells on wooden ships and realized the value of armored ships. In addition, they realized that either speed or protection would have to be made a priority when designing ships since a wooden ship could escape an ironclad but could not engage her. In 1858, French naval architect, Stanisas Dupuy de Lôme, built La Gloire, a steam powered wooden frigate with a screw propeller and four inches of iron plating. Britain responded with their own ironclad program. The first products of the new program, the Black Prince and the Warrior, were constructed in 1859. By 1860, France had 15 ironclad vessels under construction and Britain, by 1861, had 10.

Americans had also tried their hand at constructing an ironclad battery, although their attempt had occurred before the Crimean War. In 1843, the United States Government made a contract with Robert L. Seven and E. A. Stevens for the construction of an ironclad battery for the defense of New York. “Stevens Battery” was designed to be a 420-foot, 6,000 ton battery of seven guns encased in armor on iron ribbing at a cost of $500,000, but the project would never be completed. In addition, Donald McKay, a prominent American shipbuilder, recommended a fleet of ironclads be constructed eventually, and as an interim, he suggested that existing frigates be cut down and encased in iron. A few years later, when the secessionist crisis was heating up, the new Confederate Secretary of the Navy, Stephen R. Mallory, believed that ironclad warships would be the ultimate naval weapon; he declared that he “regard[ed] the possession of an ironclad ship as a matter of the first necessity.” He had watched the French and English efforts closely and had been involved with “Stevens Battery”. He knew that the Confederate Navy would never match the United States Navy, simply for the fact that the US already had a navy and that they had a better industrial capacity. Knowing that the new nation they were trying to build would not have the supplies or manufacturing capabilities to build their own fleet, Mallory originally looked to Europe to buy what they needed. He sent two agents to Europe: James D. Bulloch went to Liverpool, England to secure the construction of vessels to be used as cruisers to disrupt Northern maritime commerce, and Lieutenant James H. North was sent to purchase or contract the construction of ironclad warships to break the Northern blockade. North was specifically instructed to order ironclads in the Warrior type of Britain or the Gloire type of France. Unfortunately for the Confederacy, Lieutenant North would fail on his mission to procure ironclad vessels. After North’s failure, Mallory had to look to construct ironclads inside the Confederate States. Mallory and the Confederacy would get a chance at constructing their own ironclad when Gosport Navy Yard in Norfolk, Virginia fell to the Confederacy along with naval supplies and the frigate USS Merrimack.

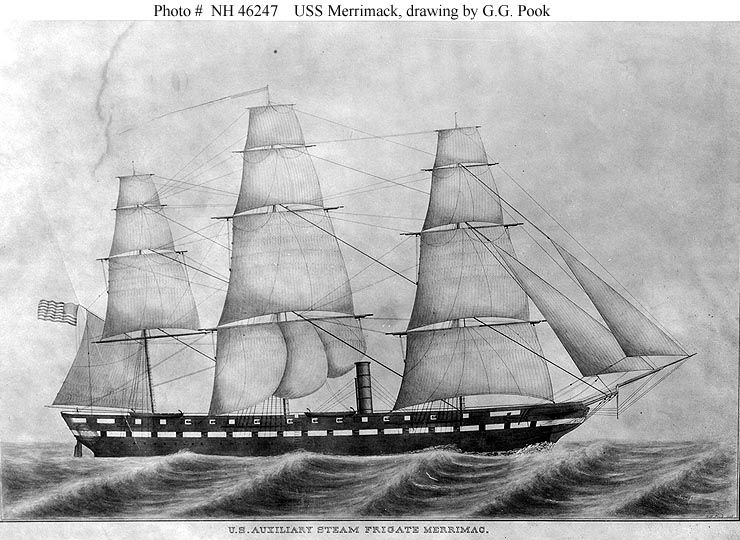

The USS Merrimack was a first-class steam frigate with screw propeller and auxiliary steam power that had been first authorized by President Franklin Pierce in 1854. After being launched on June 14, 1855 and completed on February 25, 1856, the Merrimack saw service in the West Indies before being decommissioned in 1857 for repairs. She was re-commissioned on September 11, 1857 for service as a flagship in the Pacific but was sent back to the navy yard at Norfolk and again decommissioned for repairs on February 16, 1860. She remained there, unequipped and with her engines dismantled and needing repairs, until the outbreak of Civil War in 1861.

As the crisis in the South escaladed, United States naval officers at Gosport wanted to get the supplies and ships safely to the North, but the commander of the yard, Charles S. McCauley, was slow to act due to secessionist influence, even though he was supposedly a unionist. Seeing McCauley’s inactivity, Chief Engineer Robert Danby contacted Benjamin Franklin Isherwood, the United States Navy’s Engineer in Chief, who alerted Gideon Welles, the Secretary of the Navy. On April 10, 1861, Welles issued orders to McCauley to ready the Merrimack for movement deeming it “important that that [she] should be in condition to proceed to Philadelphia or to any other yard, should it be deemed necessary, or, in case of danger from unlawful attempts to take possession of her, that she may be placed beyond their reach.” The work spurred by this order soon stopped after protests by secessionists. Welles dispatched Isherwood and Commodore James Alden to Norfolk to prepare the Merrimack to take her north and ordered that all sailors not otherwise occupied be brought down to crew her on her journey. During this time, the first shots of the Civil War were fired at Fort Sumter. Alden arrived to find that all the workmen had deserted the navy yard, but on inspecting the Merrimack estimated that they could have her ready to sail in three days. Before the work was finished, however, Virginia seceded from the United States and all the officers resigned their commissions. It now became imperative that the Merrimack be ready to sail and Gideon Welles sent new orders to McCauley: “The vessels and stores under your charge you will defend at any hazard, repelling by force, if necessary, any and all attempts to seize them, whether by mob violence, organized effort, or any assumed authority.” The day after those orders were issued, on April 17, Isherwood and Danby reported to McCauley that the Merrimack was ready to sail; they had reconstructed her engines and the USS Cumberland had arrived with the crew needed to sail her north. However, McCauley would not let the Merrimack sail that day and the next day ordered her boilers to be shut down. Hearing this, Welles relieved McCauley of command and replaced him with Commodore Hiram Paulding who arrived at the yard to find all the ships scuttled or sunk and the guns spiked. In his report to Secretary Welles, McCauley would state that he made the decision to destroy and abandon the yard after Virginia state troops began converging on Norfolk and setting up batteries near the yard; Paulding, however, reported that he saw such no hostile demonstrations.

Commodore Paulding knew that he did not have an adequate force to hold the yard so he made the decision to destroy as much as he could to keep the supplies out of Confederate hands and then abandon the navy yard. On the night of April 20 into April 21, combustible materials such as cordage, rope, ladders, and gratings were piled before the mainmast of the Merrimack. The decks and beams were soaked in turpentine and cotton-waste ropes soaked in turpentine were laid across the pile on the deck with the ends hanging off the sides where they could be easily fired. At 2:00 AM the signal was given to fire the Merrimack and the navy yard and then the men still loyal to the Union left. The destruction was done shoddily and the Confederates managed to tame the fire quickly enough that a lot of valuable supplies fell into the hands of the Confederates.

At first the Merrimack was not considered as useful in the construction of ironclads, it would take much thinking and planning before that plan emerged. Stephen Mallory had already been meeting with naval and ordnance expert John M. Brooke about the construction of ironclads and the capacity of the Confederacy to do so. A shipbuilder was called from Norfolk to draw out a plan but the employee they sent did not know drafting and was sent back because he could not draw the plans. Then John L. Porter, constructor at Norfolk Navy Yard, and Confederate Navy Department Chief Engineer William P. Williamson were brought in to consult on the idea. On June 23 the four held their first meeting and Brooke presented the plans he had come up with in consultation with Mallory. Brooke had designed a shallow-draft vessel with a casemate, in a similar, but not identical, style to floating batteries, with sloping sides to house broadside guns and pivot guns in the fore and aft. The ends of the boat would be similar to the ends of a regular ship and would extend past the casemate in a similar design to the British Warrior and Black Prince classes. The ends of the ship and the eaves of the casemate would be submerged at least two feet under water; this gave the vessel better speed and buoyancy and was used for protection since the engines and vitals of the ship would be underwater. Iron plating would protect everything that was above the waterline. Constructor John L. Porter also presented a design and model at that meeting, of an ironclad he had designed while working on another project in 1846. His model consisted of an ironclad casemate with inclined sides over a hull which terminated at the ends of the shield forming a box-like vessel. The hull would be flat-bottomed and have a shallow draft with all lower parts submerged.

Brooke and Porter collaborated in merging their designs to create the final design plan for an ironclad ship. Their individual plans had been very similar; they agreed on the shallow draft and had specified almost the same type of casemate. The real difference between the plans was the ends of the ship. Porter was thinking of the French floating batteries in the Crimean War with their boxy shape and Brooke was thinking of the European iron warships in extending the ends past the casemate. Porter agreed to extending and submerging the ends as in Brooke’s design. On June 25, Mallory met again with Brooke, Porter, and Williamson to finalize the ironclad plans. All parties approved of the plan Brooke and Porter designed but were dismayed to realize that it would take at least a year for it to be realized. Williamson then suggested that they use the machinery from the captured Merrimack. When the Federals had tried to destroy the Merrimack they had sunk her and then set her on fire; in consequence, her hull and machinery had been saved by being underwater during the fire. From this suggestion came the idea that they could use the entire Merrimack as the base for the design they had just approved. The Merrimack had been raised in May and put into dry dock at an expense of $6,000. After examination she was valued at only $250,000. To restore her to her former status as a wooden frigate that would be useless against Union fortifications would cost an estimated $450,000, but to convert her into an ironclad would cost only $172,523. Since the Merrimack was useless otherwise, and because it was cheaper to convert her into an ironclad, they agreed to try turning her into a ten-gun ironclad vessel. In addition, with the lack of resources held by the Confederacy and the time constraints, as Mallory stated, “It would appear that this is our only chance to get a suitable vessel in a short time.”

Brooke, Porter, and Williamson began work right away. Porter performed the duties of constructor while Williamson concentrated on the engines and Brooke worked with the iron plating and ordnance. Acting Chief Engineer Ramsay was also brought in to assist on the construction; he had been the Merrimack’s Second Assistant Engineer and knew the ship well. Brooke and Williamson went to Tredegar Iron Works in Richmond to locate engines to repair the Merrimack but none were available. This meant that Williamson had to repair the existing engines extensively although there are no records attesting to what he did. The ship would continually suffer from engine trouble, but the constructors did not have the time or resources to do otherwise.

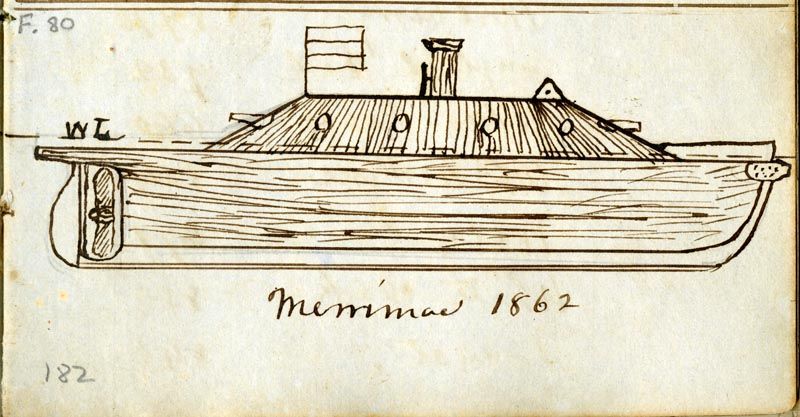

At Norfolk, Porter began to construct the hull and wooden casemate out of the wreckage of the Merrimack. Above the waterline was charred and twisted, so the first thing Porter did was cut down to the berth deck, three feet over the unladen waterline. He had to modify his original plans, however, to accommodate the Merrimack. At the line at which he wanted to cut, nineteenth feet up the hull, he would cut one foot into the propeller which would have diminished the size of the propeller and decreased the speed of the vessel. Porter raised the line one foot at the stern and cut the hull down to a height of nineteen feet at the bow and twenty feet at the stern. From there he began building the gun deck which would lay two feet above the water line and extend for roughly 178 feet. The deck was thirty feet wide which meant the cannon had to be staggered because of their recoils. By the end of July the deck was laid and the casemate was in the beginning stages of construction. The casemate was 178-180 feet long to cover the gun deck with sides that sloped upward at a thirty-five degree angle. The backing of the casemate consisted of twenty-four inches of wood: fourteen inch thick rafters of yellow pine were bolted together at the thirty-five degree angle, then four inches of pine was fastened horizontally, and then another course of four inch thick oak plank was placed vertically. The sides of the casemate extended to seven feet above the gun deck. One member of the crew remarked that the sides of the shield looks like the “Mansard roof of a house,” but, he noted “…the sight of the black mouthed guns peeping from the ports gave altogether different impressions and awakened hopes that ere long she would be belching fire and death from those ports, to the enemy….” The sides joined up with a flat top fourteen inches wide and covered with an iron grating of two-inch iron in a two-inch square mesh. There were four hatches in the mesh: one near each end and one on either side of the smokestack. Beyond the casemate the main deck extended twenty-nine and a half feet to the bow and fifty-five feet to the stern, making the entire vessel 262 feet and nine inches long. A false bow, probably built up of twelve-inch by twelve-inch timber, was placed on the forward deck to prevent the water from curing up into the forward port and also placed in front was a conical pilothouse of twelve-inch thick iron with four sight holes. At the aft a fantail was built to extend over the rudder and the seventeen foot, four-inch diameter bronze Griffith’s screw propeller to protect them from collisions.

On the bow of the ship, submerged two feet under water, a 1,500 pound cast-iron prow was attached to the stem of the Merrimack and protruded two feet or four feet, depending on the account. According to Brooke, the prow was not part of the original plan; it was added later when the ship was already advanced in construction. Secretary of the Navy Mallory probably insisted on its inclusion. The idea of a ram on a ship was being reintroduced into naval warfare because steam power allowed the ship to be controlled enough to ram a target. When Mallory gave command of the James River defenses and the newly commissioned Virginia to Franklin Buchanan in February of 1862 he stressed the use of the ironclad as a ram:

Her powers as a ram are regarded as very formidable, and it is hoped that you may be able to test them. Like the bayonet charge of infantry, this mode of attack, while the most distinctive, will commend itself to you in the present scarcity of ammunition…Even without guns the ship would be formidable as a ram.

The Virginia’s use of her ram would be one of the ways she revolutionized naval history.

Of course, an ironclad is not an ironclad without the iron plating. In July 1961 Brooke contracted Tredegar Iron Works in Richmond to make iron plating at six-and-a-half cents per pound. Originally the plates were to be one-inch think, eight-inches wide and of varying lengths. To do this, Tredegar had to convert their machinery and train their workers in the construction of the iron plates. Three hundred tons of scrap iron were gathered from the ruins of Gosport Navy Yard and railroad iron was scavenged from the captured sections of the Baltimore & Ohio railroad as well as bought from Confederate railroad companies that were located too close to Union lines to operate. Then Brooke constructed tests at the batteries on Jamestown Island to determine the thickness the plating should be and at what angle it should be laid. There had been studies done in Europe on iron-plated ships but the Confederacy did not have that information, so Brooke had to determine the facts for himself. He constructed targets to resemble the twenty-four inch thick wooden casemate of the Merrimack and inclined them at a roughly thirty degree angle. He covered the targets with three one-inch thick iron plates. At a distance of three hundred yards an eight-inch solid shot with a ten pound charge penetrated the iron and entered five inches into the wood. His original plan of three-inch iron plating would not be enough to make the Merrimack’s casemate impenetrable. Brooke rebuilt the targets with four inches of iron plating (two two-inch plates) with the same wooden backing and angle. An eight-inch solid shot with a ten pound charge and a nine-inch shell weighing seventy pounds also with a ten pound charge shattered the outer layer of plating, cracked the inner plates, but left the wood undamaged. Brooke revised the plan for the Merrimack’s armor to be two layers of two-inch iron plating. This caused problems at Tredegar because they had to re-calibrate their machinery and the holes in the plates could no longer by punched, they had to be drilled which made the process slower and more expensive. Seven hundred tons of iron was brought from Richmond during the course of the construction. Railroad transportation was often delayed because the lines were being used for transporting and supplying the army, so the last shipment of iron plates did not arrive at Norfolk until February, 12, 1862. The plates were put on in two courses, the first horizontally and the second vertically. They used the one-inch plates on the sides and in a course running around the hull to three feet below the water level. The two-inch plates they used fore and aft as well as on the sides of the casemate.

Brooke also determined what guns would be used in the battery aboard the Merrimack. In correspondence between Lieutenant Catesby ap R. Jones, Executive Officer of the Merrimack/Virginia, and Lieutenant Robert Dabney Minor, who was assisting Brooke in this endeavor, in September 1861, Catesby expresses his wish for the largest guns possible to be mounted in the Merrimack and recommends the Army X-inch Sea Coast Howitzer as the most serviceable gun if mounted on a carriage. Minor responds back that while heavy guns would be mounted they would be 14,000 pound IX-inch guns. Jones argued that if X-inch guns were unavailable then XI-inch guns would be better than IX-inch guns because the bigger shells would have more accuracy and explosive force. In the end Brooke chose nine-inch Dahlgren smoothbores for six broadside ports. For the fore and aft ports he designed a seven-inch forty-two pounder rifled gun weighting 14,000 pounds with iron bands around the breech to allow for a bigger charge of powder. In addition to the two seven-inch Brooke rifles, Tredegar also made two 6.4-inch Brooke rifles for the ship.

On February 17, 1862, the former USS Merrimack was officially commissioned and christened the CSS Virginia. Despite the name change, she has always been known as the Merrimack, to the chagrin of some southerners. She was completed in March 1862, nearly 100 out of the 1,500 workers volunteering to work overtime without pay in order to complete the Virginia in time to meet the Union’s already completed Monitor. One of the last tasks the constructors had to do was to submerge the Virginia to the proper depth. Because of Porter’s adjustments in the very beginning when he was cutting the hull down, the draft had increased and so had the buoyancy by about two hundred tons. It was vital that the eaves of the casemate be submerged under the waterline, or the vulnerable hull, covered for only three feet with one-inch iron plating, would be exposed to enemy fire. As one crew member states, “Their fire appeared to have been aimed at our ports. Had it been concentrated at the water-line we could have been seriously hurt, if not sunk.” Pig iron was placed on the deck ends and in the spirit room to submerge her to the proper depth, and even then it was barely enough.

It is difficult to reconstruct the CSS Virginia; there are no photographs of the ship like there are of the Monitor. The vessel had such a short life that there are few accounts outside those who worked on it or encountered it in battle. These men often described the Virginia in vague terms such as “what looked to all appearances looked like a roof of a very large barn belching forth smoke as from a chimney on fire,” “a large vessel shaped like a roof of a house, with one smokestack,” or “a sunken house with nothing but the roof above the tide.” Contemporary accounts and later sources are contradictory and full of discrepancies as are the drawings and paintings which are our only visual evidence besides sketches and plans done by the three main constructors.

The Virginia was only engaged in a few battles in her short existence. On March 8, 1862, she entered into battle for the first time against Federal vessels. Though still unfinished, the Virginia rammed the USS Cumberland and sank her, destroyed the USS Congress, damaged the USS Minnesota, and chased away the USS St. Lawrence and USS Roanoke. The next day, the Virginia and the Monitor locked in a five hour battle in which the Virginia finally dislodged the pilot-house of the Monitor and caused it to retreat into shallow waters where the Virginia could not follow because of her deep draft. The damage done to the Virginia speaks to the innovative design produced by Brooke and Porter. There were about one hundred indentations in the armor and six outer plates were cracked. There was no damage to the second course of wood. This may be a slight over exaggeration since a member of the crew recalled:

The effect of a shot striking obliquely on the shield was to break all the iron, and sometimes to displace several feet of the outside course; the wooden backing would also be broken through but not displaced. Generally the shot were much scattered; in three instances two or more struck near the same place, in each causing more of the iron to be displaced, and the wood to bulge inside. A few struck near the waterline. The shield was never pierced; though it was evident that two shots striking in the same place would have made a large hole through everything.

According to John W. H. Porter, son of John L. Porter, the Virginia’s design was superior to that of the Monitor because the angled sides caused enemy shots to glance off the armor while the Monitor’s armor had to resist shot at a perpendicular force. On May 11, 1862, after only two months in active service, the career of the CSS Virginia ended. On May 10, the Confederates evacuated Norfolk without notifying the Virginia. The Virginia sent a gig to the city for news and it returned under enemy fire with news of the evacuation. The officers decided to try to lighten the Virginia enough to sail up the James River but her draft was too great and she ran aground near Craney Island. With no other options before them, the crew abandoned the Virginia and, as the last boat left, set her on fire. At 4:58 AM on May 11, 1861, the Virginia exploded.

For the first time two ships made under the new standards of the nineteenth-century naval revolutions clashed in combat. While this battle was of great importance, the Virginia holds a higher claim to the title of revolutionary. It was the first ship of its kind build with all five of the naval revolutions considered and it was the first American ironclad. The Monitor was built only in response to what the Confederate Navy was building and how. In addition, while the Battle of Hampton Roads was important, it proved only that two ironclad ships could not gain the advantage over each other in battle. The Virginia’s engagement with the Cumberland and Congress marked the end of the era of wooden ships, as noted by an article in the Confederate Veteran:

…the Merrimac was the most remarkable naval craft ever floated, and the results of her successful battle with the Cumberland and Congress would revolutionize the navies of the world and would be felt for centuries to come. The moment the Merrimac successfully rammed the Cumberland and sent her to the bottom with colors flying and guns firing the navies of all Europe, representing an investment of billions of money, were rendered useless.

The age of the metal warships was being ushered in, and the age of the great wooden ships ushered out, by the hastily constructed concoction of a rebellion that would fail but would revolutionize naval history through the CSS Virginia.

Bibliography and Further Reading:

Barthell, Edward E., Jr. The Mystery of The Merrimack. Edward E. Barthell, Jr. 1959.

Besse, S. B. C.S. Ironclad Virginia: With Data and References for a scale model (Museum Publication No. 4). Newport News, VA: The Mariners Museum,1937.

Boynton, Charles B., D. D. The History of the Navy During the Rebellion. New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1867.

Campbell, R. Thomas. Voices of the Confederate Navy: Articles, Letters, Reports, and Reminiscences. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2008.

Catesby ap R. Jones. “‘The ‘Virginia,’ The First Confederate Ironclad, Formerly The United States Steam Frigate ‘Merrimac’: A Narrative of her Services by Catesby ap R. Jones, Her Executive and Ordnance Officer and Commander, in Her Fight With the ‘Monitor.’” Southern Historical Society Papers, December 1874.

Catesby ap R. Jones to Robert Dabney Minor, September 16, 1861. Southern Historical Society Papers.

Catesby ap R. Jones to Robert Dabney Minor, September 22, 1861. Southern Historical Society Papers.

The Confederate Veteran.

Daly, R. W. How the Merrimac Won: The Strategic Story of the C.S.S. Virginia. New York: Thomas Y. Cowell, 1957.

Davis, William C. Duel Between the First Ironclads. New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 1995.

Flanders, Alan B., and Captain Neale O. Westfall, ed. Memoirs of E. A. Jack: Steam Engineer, CSS Virginia. White Stone, VA: Brandyland Publishers, 1998.

The Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion.

Porter, John W. H. A Record of Events in Norfolk County, Virginia, From April 19th, 1861, to May 10th, 1862, With a History of the Soldiers and Sailors of Norfolk County, Norfolk City and Portsmouth who served in the Confederate States Navy. Portsmouth, VA: W. A. Fiske, Printer and Bookbinder, 1892.

Roscoe, Theodore, and Fred Freeman. Picture History of the U.S. Navy: From Old Navy to New, 1776 to 1897. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1956.

Quarstein, John V. The Battle of the Ironclads. Charleston, SC: Acadia Publishing, 1999.

Simpson, Jay W. Naval Strategies of the Civil War: Confederate Innovations and Federal Opportunism. Nashville, TN: Cumberland House, 2001.

Smith, Gene A. Iron and Heavy Guns: Duel Between the Monitor and Merrimac. Abilene, TX: McWhiney Foundation Press, 1998.

Spencer, Warren F. The Confederate Navy in Europe. University, AL: The University of Alabama Press, 1983.

Stern, Philip Van Doren. The Confederate Navy: A Pictorial History. New York: Bonanza Books, 1962.

Silverstone, Paul H. Civil War Navies, 1855-1883. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2001.

Kathleen Logothetis Thompson graduated from Siena College in May 2010 with a B.A. in History and a Certificate in Revolutionary Era Studies. She earned her M.A. in History from West Virginia University in May 2012. Her thesis “A Question of Life or Death: Suicide and Survival in the Union Army” examines wartime suicide among Union soldiers, its causes, and the reasons that army saw a relatively low suicide rate. She is currently pursuing her PhD at West Virginia University with research on mental trauma in the Civil War. In addition, Kathleen has been a seasonal interpreter at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park since 2010 and has worked on various other publications and projects.