The Blue and Gray in Black and White: The Media’s Portrayal of Veterans during the 75th Anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg

/“There’s Still Life in the Old Boys Yet!,” a newspaper article emphatically exclaimed. An accompanying photograph portrayed Union veteran Tim Flaherty, well into his nineties, dancing a jig for his comrades. The year was 1938, the July heat sweltering, and the final grand reunion of the blue and gray well underway. Seventy-five years after the battle of Gettysburg, 1,845 veterans were able to reach the rolling hills of southern Pennsylvania to once more commemorate the defining four years of their generation.

However, this reunion was different than the others.

Nearly 775,000 tourists clogged Gettysburg’s narrow alleys, modern military equipment was used to reenact iconic moments of the battle, and over one hundred national press outlets insured the nation was saturated with news concerning the Battle of Gettysburg and its significance, perhaps for the first time since the battle itself. Over the four days of commemoration, the media’s representation of the aging veterans would mirror a fundamental change in the commemoration of the American Civil War. Memorialization would shift from being largely for the veterans to for the nation, and Tim Flaherty and his comrades would be placed firmly into antiquity.

One unique characteristic of media coverage concerning the 75th Anniversary was the overemphasis of the veterans’ age. The average age of the attending veterans was ninety-four, and they were all aware that this would be the final Gettysburg reunion. The “tent city” provided for the veterans comfort as much as possible, including a fully functional hospital and over four hundred wheelchairs, complete with Boy Scouts and National Guardsmen to push them. Many veterans invited were forced to decline attending due to poor health, and others were truly risking their lives in order to reach Gettysburg.

The language used by media outlets stressed this impending mortality with vigor. Terms such as “old-timers,” “hobbling,” and “feeble” were common. One article even commented that the reunion “crowded out the thought that the time is closing in and that the remnants of the once proud Union and Confederate armies soon must join their comrades.” This characterization seemed to survive the ensuing decades, as an article about the anniversary in 1979 referred to it as the “graybeard reunion.” However, even more damaging was the presentation of the veterans as not only aging, but also cartoonish and childlike. One headline stated that the “Gettysburg Camp Grand Talk Fest for Veterans,” which went on to describe a ninety-five year old Confederate doing a ‘lively buck and wing dance,” as well as implying that the only modern day issue concerning Philadelphia resident Allen T. McFarland was the outcome of the Phillies-Giants baseball game. Articles such as these romanticized veterans at best and portrayed them as one-dimensional and simplistic at worst. Even more significantly, the emphasis on age implied that veterans belong to a past era, instead of as a part of modern society.

The impetus for organizing this reunion was not from the veterans or the veteran’s organizations, but from local and state commissioners under the leadership of Gettysburg Chamber of Commerce Executive Secretary Paul Roy. Hoping to renew interest in the lucrative practice of reunions and monument building which characterized the late 19th century, Roy saw the anniversary as an opportunity to “sell” Gettysburg to the nation. Obviously, a considerably smaller number of veterans attended the 75th Anniversary in comparison to the 50th, but another key difference lay in the significantly larger number of tourists in 1938. Automobile travel, improved highways, and increased focus on catering to families ensured both access to Gettysburg and an enjoyable experience upon arrival. Interactions between the visiting families and the few remaining elderly veterans were largely for the benefit of the tourists searching for an authenticated experience of the past. In many ways, veterans became integral to creating a unique experience for visitors as part of a commemorative landscape.

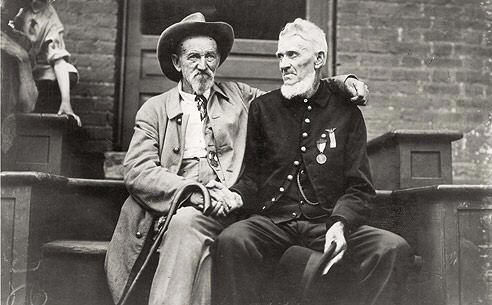

Media outlets and politicians continued to perpetuate a narrative of unity, particularly the reconciliationist fervor that gripped the 50th anniversary celebrations of 1913. For example, the Christian Science Monitor claimed that this reunion had the opportunity to prompt the “disappearance of a remnant of sectionalism and the emergence of a wider sense of patriotism that forgives – and forgets – the separating bitterness of 1861-1865.” Many of the veterans seemed to support this attitude, or were at least quoted by the media as doing so, such as ninety-three year old Confederate veteran William H. Freeman, of Wetumka, Oklahoma, who explained to a reporter, “We’re here to bury the hatchet and forget all about that little fus,” and his companion, a Union veteran who sentimentally replied, “We’ve done that long ago.” However, reconciliation itself is an oversimplification, as many of the veterans did not share what has come to be seen as a pervasive movement towards a common heroic past. When extending invitations to the remaining veterans organizations, Roy had trouble convincing both the United Confederate Veterans and the Grand Army of the Republic that a final reunion would be beneficial. Many officials of the G.A.R. still held bitterness toward the Confederate invasion of the north, and General Harry Rene Lee, leader of the UCV, went as far as to exclaim “Young Man, I thought you would come down here and try to get my organization to go to Gettysburg to meet with those damnyankees… The answer is no, emphatically and positively no.” While both organizations eventually gave their support, their initial reactions illustrate that sectional bitterness was by no means relegated to a distant past in 1938.

Certain aspects of the reunion also spoke to the predominance of sectionalism in interactions between the old soldiers. Ninety-four year old Union veteran David Reed believed it was unsafe for veterans to carry their rifles, implying the only barrier between reunification and sectional bitterness was the lack of weapons. Although both Union and Confederate flags were presented to each veteran upon arrival, debate over the use of the Confederate flag existed. For example, G.A.R. representative James Willett referred to it as “the infernal banner,” and many took up the battle cry “No rebel colors!” This certainly did not speak to the generalization that the veterans now existed as comrades “without heed for stars and stripes, or stars and bars.” A less venomous account of sectional confusion came from Annette Tucker, who was participating in the reunion as her father’s attendant. She described in her account of the commemoration that displaying the Confederate flag at the reunion “didn’t seem the proper thing to do,” but that she brought it home to “perhaps use at our own U.D.C. [United Daughters of the Confederacy] Meetings.” This illustrated that the feeling of unity present at the reunion did not necessarily have permanence throughout the nation. Even organizational choices such as having separate Union and Confederate camps, or the fact that the majority of the veterans chose to wear their old uniforms, subtly implied that divisions between the two sides still existed.

Furthermore, the motivations for veterans to attend the reunion were not necessarily geared towards reconciliation, or even idealistic at all. African-American veteran Frank Lilley may have come to show that the Civil War was not only a white experience, as the reconciliationist narrative suggests. Many came to reunite with old comrades they had not seen in years. Another veteran stated that he travelled to Gettysburg to find a tree, explaining, “I was wounded near that tree, and all I want in this world is to find it. When I do, then I’ll be ready to die.” Even this small group of veterans was not monolithic in their intentions for and assigned significance of the reunion.

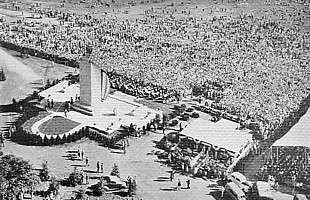

Perhaps the most intense media coverage centered on the dedication of the only monument constructed in 1938. The “Eternal Light Peace Memorial,” unveiled with much pomp and circumstance at the closing of events on July 3rd, was dedicated to “the memory of every man, woman and child, North and South, who participated in any way in the War Between the States,” as well as a “perpetual symbol of peace.” The design of the memorial was institutional, imposing, and vastly different from the monuments erected by the veterans in preceding decades. Composed primarily of a forty-foot limestone shaft resting on an enormous platform, the monument towers over the battlefield. Unlike regimental or state monuments erected by veterans, this behemoth structure contains no mention of casualties, by either name or number. In fact, the only name mentioned on the monument at all is that of Abraham Lincoln, along with the quote, “With firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right.” At the top of the memorial is the gas-lit eternal flame, accompanied by the words “An enduring light to guide us in unity and fellowship.” This monument utilized both the legacy of Lincoln and Civil War veterans as models for future generations. Although this monument was intended to be the “final tribute of honor and respect” the nation would pay to “these men of courage,” it is clear that the only permanent structure to emerge from the 1938 reunion was intended for posterity.

Superficially, the Eternal Light Peace Memorial and its dedication are tangible representations of reconciliation. Engraved with the words “Peace Eternal in a Nation United,” the monument was draped in a huge American flag for its July 3rd unveiling. Two veterans, one Union and one Confederate, helped uncover the monument while the other veterans watched from a special sheltered grandstand. Roosevelt’s concise, nine-minute speech contained lines such as “All of them we honor, not asking under which flag they fought then—thankful that they stand together under one flag now.” The president’s words were not only heard by the 200,000 individuals in attendance, but also broadcast on national radio. Not only did the press seize this message, but the light’s dedication seemed to have a profound effect on those in attendance as well. Annette Tucker, the daughter of a Confederate veteran who had grappled with the appropriate time to display a Confederate flag earlier during the commemoration, wrote, “Since we have lighted the Peace Memorial, I don’t see any use in displaying it at all. In the language of the march I say, ‘The Stars and Stripes forever.’"

However, this monument’s significance goes beyond lauding past compromise. It is both a commentary on the current challenges faced by the United States in the 1930s and a projected hope for the nation’s future. By stating, “Immortal deeds and immortal words have created here a shrine of American patriotism,” Roosevelt not only placed the story of Gettysburg into the triumphal narrative of American history, but also created the ability for Gettysburg’s legacy to be applied to current issues, present and future. Asserting that although the challenge of preserving democracy takes different forms for different generations, perhaps alluding to the test of democracy presented by totalitarian regimes in 1930s Europe, the president then used the legacy of Civil War veterans to call “upon the nation to dedicate itself to eternal struggle for peace through democracy.” The press seized this theme as well, with headlines crying, “Gettysburg Vets Saved Great Democracy for the World,” and connecting this ancestral legacy as the guardians of democracy to the belief that “Americans today are the trustees of popular liberty for the whole world.” The application of the struggles of veterans during Civil War to current issues, and the idea that the veterans’ legacy was that of enduring peace, created from the Civil War a usable national past.

In sharp contrast to the overture to peace on the evening of July 3rd was the flagrant display of American military might on July 4th. Appropriately characterized as a “monster military parade” by the Philadelphia Inquirer, the display included demonstrations of modern weaponry such as tanks, cavalry and artillery demonstrations, and even air shows. This show of martial strength seems very odd when juxtaposed with the dedication of the Peace Light the day before, alluding to the idea of peace by force. Again, this commemorative exercise placed the veterans firmly in the past. The “guests of honor,” surrounded by elaborate decorations reminiscent of a presidential inauguration, they watched “demonstrations of arms beside which their ancient muskets and muzzle-loading cannon were mere toys.” The event culminated in a strange depiction of how Pickett’s Charge would have been conducted in 1938, including modern infantry formations and showy aerial maneuvers. A strange merging of past and present, a romanticized landscape of past martial glory was infiltrated by physical representations of current military strength.

Through the lens of the media, we can see that the 75th Anniversary at Gettysburg was a watershed in Civil War memory, providing both the last example of commemoration for and by veterans, and the first truly national commemorative experience. The veterans experience was antiquated, oversimplified, and usurped into a developing collective narrative. The veterans became living monuments, caught between a bygone era and a rapidly changing contemporary world, a connection for tourists seeking an authentic nineteenth century experience.

However, these veterans were not made of stone. They were men, men with opinions on how their past should be commemorated. Men with voices, who were lost in a sea of flashing cameras, formidable tanks, and patriotic pomp.

They were more than specters from a bygone era. Tim Flaherty was more than a gray beard and a spirited jig.

Becky Oakes, a graduate of Gettysburg College, is currently finishing her master’s degree in 19th-century U.S. History and Public History at West Virginia University. Becky’s research focuses on Civil War memory and cultural heritage tourism, specifically the development of built commemorative environments. She also studies National Park Service history, and has worked at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park, Gettysburg National Military Park, and the Civil War Institute at Gettysburg College.

Sources and Further Reading:

“75th Anniversary, Battle of Gettysburg [0125] - Unveiling of the Eternal Light Peace Memorial :: Civil War Reunions and Reminiscences.” Accessed April 28, 2014. http://gettysburg.cdmhost.com/cdm/singleitem/collection/p15059coll5/id/296/rec/125.

Cohen, Stan, ed. Hands across the Wall: The 50th and 75th Reunions of the Gettysburg Battle. 3rd rev. printing. Charleston, W. Va: Pictorial Histories Pub. Co, 1997.

“Eternal Light Peace Memorial at Gettysburg.” Accessed April 28, 2014. http://www.gettysburg.stonesentinels.com/Other/Peace.php.

“Franklin D. Roosevelt: Address at the Dedication of the Memorial on the Gettysburg Battlefield, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.” Accessed April 28, 2014.

“Gettysburg Vets Saved Great Democracy for the World.” Philadelphia Record. July 4, 1938. V11-62b. Gettysburg National Military Park.

“Here and There with the Vets.” Star and Sentinel. July 9, 1938.

Linenthal, Edward Tabor. Sacred Ground: Americans and Their Battlefields. 2nd ed. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993.

Martin, Paul. “Civil War Vets Hold Last Camp: Two Thousand Men of Blue and Gray Swap Takes in Reunion at Gettysburg".” Rocky Mount Herald. July 1, 1938. V11-62. Gettysburg National Military Park.

O’Leary, Jeremiah. “Gettysburg Revisited and Remembered.” Washington Star. July 5, 1979. V11-62. Gettysburg National Military Park.

“Old Blues, Grays Become One for 75th Reunion at Gettysburg.” The Washington Times. July 4, 1992. V11-62. Gettysburg National Military Park.

“President Makes Eloquent Appeal for World Peace.” News and Observer. July 4, 1938. V11-62. Gettysburg National Military Park.

“President Will Dedicate Gettysburg Light Today.” News and Observer. July 3, 1938. V11-62. Gettysburg National Military Park.

Proctor, Harry G. “Gettysburg Camp Grand Talk Fest for Veterans.” The Evening Bulletin. July 1, 1938. V11-62b. Gettysburg National Military Park.

“Program: 75th Anniversary Battle of Gettysburg, Final Reunion of the Blue and Gray.” Gettysburg National Military Park, July 29, 1938. V11-62c. Gettysburg National Military Park.

“The Blue and Gray: Age Mellows Memories on Seventy-Fifth Gettysburg Anniversary.” Newsweek, July 11, 1938. V11-62. Gettysburg National Military Park.

“"There’s Still LIfe in the Old Boys Yet!” The Morning Herald. July 4, 1938. V11-62. Gettysburg National Military Park.

Tucker, Annette. “The Gettysburg Reunion,” n.d. V11-62. Gettysburg National Military Park.

Unrau, Harlan D. “Administrative History: Gettysburg National Military Park and National Cemetery, Pennsylvania.” National Park Service, 1991.

“Veteran Leaders Plead for Peace: Spirit of Fellowship Prevails at Gettysburg; Woodring Lauds Old-Timers".” News and Observer. July 2, 1938. V11-62. Gettysburg National Military Park

“Veterans Depart from War Scene: Say Sad Farewells as Their Last Reunion Comes to End at Gettysburg.” News and Observer. July 6, 1938. V11-62. Gettysburg National Military Park.

“Veterans Enjoy Army Spectacle: Modern Fighters Stage Spectacular Maneuvers for Heroes at Gettysburg.” News and Observer. July 5, 1938. V11-62. Gettysburg National Military Park.

“Visit Gettysburg: Blue and Gray Reunion, 75th Anniversary Battle of Gettysburg 1938.” Gettysburg, PA, 1938. V11-62c. Gettysburg National Military Park.

Weeks, Jim. Gettysburg: Memory, Market, and an American Shrine. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 2003.