Sesquicentennial Spotlight: Destruction at Sailor's Creek

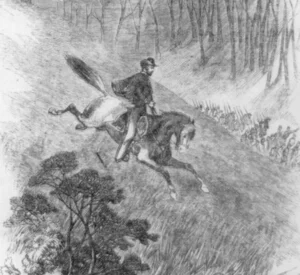

/The Battle of Sailor’s Creek, many will argue, was a final death knell for Lee’s army. In the day’s engagements Lee lost about a quarter to one-third of his army (depending on which casualty report you look at), 8,800 men out of the roughly 30,000 effectives he had that morning. Of these casualties, around 7,700 were captured or surrendered—one of the largest surrenders without terms during the war. Among this number was almost the entire corps of Richard Ewell—3,400 of his 3,600 men were among the dead and captured. Ewell himself was taken prisoner, along with seven other Confederate generals: Joseph B. Kershaw, Montgomery Corse, Eppa Hunton, Dudley M. DuBose, James P. Smith, Seth Barton, and Robert E. Lee’s son, George Washington Custis Lee. Anderson’s corps lost around 2,600 out of 6,300 and Gordon’s casualties numbered at 2,000.

Read More